Richard Denison, Ph.D., is a Lead Senior Scientist.

Under an obscure and opaque – and increasingly used – exemption that EPA provides under the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), EPA has been quietly approving companies’ requests to introduce new poly- and per-fluorinated substances (PFAS) onto the market. And it seems to be ramping up. [pullquote]Under this EPA the “low-volume exemption” (LVE) application process is proving to be very smooth sailing for getting new PFAS onto the market.[/pullquote]

PFAS is a class of chemicals that are showing up as environmental contaminants all over the country. They are linked to large and growing list of adverse effects on human health. These concerns have led to increased scrutiny about EPA’s actions to allow new PFAS to enter commerce. EDF and others have raised concerns about a number of premanufacture notices (PMNs) companies have filed seeking approval to introduce new PFAS into commerce (see here and here); the PMN process is the standard way in which companies are to notify EPA of their intent to start manufacturing a new chemical.

But EPA has created other pathways to quickly get a chemical on the market, whereby companies can apply for an exemption from the PMN process. As documented in this post, we have identified a whole lot of PFAS coming into EPA’s new chemicals program through exemptions, and most of them are getting quickly approved. Worse yet, this side process is highly insulated from public scrutiny.

The most frequently used of the exemptions available to companies is the so-called “low volume exemption” (LVE). In exchange for agreeing not to make more than a specified amount of a new chemical, the company gets an expedited review – with a decision within 30 days compared to the 90 days allotted for PMN reviews.

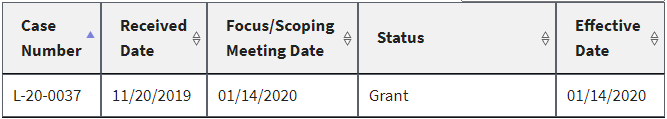

Starting in April of this year, EPA began posting the actual applications for LVEs that companies submit to EPA’s New Chemicals Program on the agency’s ChemView data portal. These postings allow, for the first time, the public to get some indication of the nature of the chemical subject to the LVE application. Prior to this time, the only public notice of LVE applications was in EPA’s status table for exemption applications, which is provided by EPA primarily to allow submitters to track their status. But that table gives no indication or description of the chemical’s identity or even the type of chemical; it provides only a case number EPA assigned to each application. Here is a screen shot of an LVE entry in the status table:

As you can see, the table provides no identifying information for the subject chemical, only its case number. Back in May of 2019, EDF requested that EPA address this failing. Among other things, we pointed out that EPA receives and reviews at least as many of these exemption applications annually (exceeding 1,000) as it does the more standard ”premanufacture notices” (PMNs), and that far more transparency around such chemicals is sorely needed. We also directed EPA to its own regulations that require EPA to provide a public list of chemicals for which exemption applications are submitted.

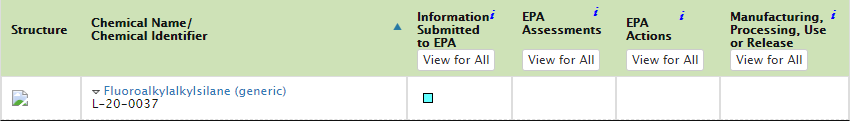

Perhaps in response to that request, EPA finally began posting these applications to ChemView a few months ago. It’s now possible, but still not easy, to connect a specific chemical description with a specific case number: By doing a convoluted advanced search using the case number, or sorting through all of the new chemical notices posted there, one can now identify at least a generic name for the chemical in each posted LVE application. Here’s a screen shot of the ChemView listing for the chemical with the case number noted above:

This is a welcome bit of progress, though still very far from user-friendly and falling far short of meeting the regulatory requirement that EPA publish a public list of chemicals for which LVE applications are received. It should also be noted that the ChemView postings are only prospective; none of the thousands of previously received LVE applications are publicly accessible.

Not to be deterred, we persevered and examined all of the LVE applications posted to ChemView that, based at least on their generic names, are for likely PFAS. We first identified 31 chemicals with posted LVE applications that include “fluor” in their names. Of these, we eliminated seven from being PFAS based on closer examination of their names.

This means that LVE applications for 24 PFAS have been posted to ChemView just since April of this year. We then had to manually cross-check their “status” by referring back to the exemptions status table to determine what if any decision EPA has made. We found that, as of today:

- 15 of these applications have been granted (i.e., the chemical is approved for market entry).

- One has been “conditionally granted,” meaning that EPA expects to grant it once the applicant has taken some additional step.

- One was declared “invalid.”

- One has yet to have a decision posted to the status table.

- Six have been “conditionally denied,” meaning that they won’t be granted until or unless the applicant proposes some unspecified additional control. It is very rare, however, that such applications are ultimately denied: Of the 43 LVE applications for all types of chemicals posted to Chemview that were initially conditionally denied, all but six were granted in the end (one was denied and five were withdrawn).

So overall, EPA has already approved two-thirds of the LVE applications for PFAS chemicals it received and posted to ChemView since April, and appears likely to approve nearly all of the remaining ones as well. In other words, under this EPA the LVE application process is proving to be very smooth sailing for getting new PFAS onto the market.

While production limits do apply to approved LVE chemicals, the actual limits are not made public nor is it clear what, if any, other conditions EPA has applied to their manufacture and use. That’s because nothing other than EPA’s decision – grant or deny – is made public. In contrast, with PMN reviews, EPA has to provide some explanation for a determination that allows a chemical to enter commerce (although there are many shortcomings here as well).

Our examination also reveals another disturbing trend: Companies appear to be using LVE applications in lieu of PMNs as a path of less resistance to getting not just PFAS but all kinds of chemicals quickly onto the market. Consider that:

- Since April, only a single PMN has been posted to ChemView for PFAS, in contrast to the 24 LVE applications posted in the same time period.

- Across all types of new chemicals, 274 LVE applications have been posted since April, compared to only 61 PMNs.

- Of these LVE applications, 183 have a final decision: 161 have been granted, while only one has been denied; the remainder were deemed invalid or were withdrawn.

So: A lot more LVE applications than PMNs seem to be coming in as of late, and a large majority of them are being approved by EPA – including for new PFAS. This matters because the LVE review and decision process is even less transparent than the PMN process.