Tom Neltner, J.D., Chemicals Policy Director and Maricel Maffini, Ph.D., Consultant

The Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA) Total Diet Study (TDS) is an important source of data for both the agency and the public to estimate exposure, track trends, and set priorities for chemical contaminants in food. EDF analyzed TDS data for samples the agency collected from 2003-2013 in our 2017 report to reveal that lead in food was a hidden health threat. In follow-up blogs using TDS data from 2014-2016, we reported that overall trends for detectable rates of lead appeared to be on the decline, especially in 2016. In our analysis, we summarized that the trends were both good news and bad news for children because there were stubbornly high rates of detectable lead in baby food teething biscuits, arrowroot cookies, carrots, and sweet potatoes.

In this blog, we analyze the latest lead in food TDS data, released by FDA in August, and we take a new look at the trends. Overall, the 2017 data reversed the progress in 2016, largely driven by the percent of samples[1] with detectable lead in prepared meals nearly doubling from 19% to 39%. The good news is that fruit juices continued their dramatic and steady drop in samples with detectable lead, from 67% in 2016 to 11% in 2017. When we compared results for baby foods to similar samples of regular fruits and vegetables, the most notable finding was that baby carrots and peeled and boiled carrots had significantly lower detection rates than baby food carrot puree. Additionally, we were surprised to find that 83 of 84 samples of canned fruit had detectable levels of lead.

Comparing 2017 with prior years – rates increased, especially for prepared meals

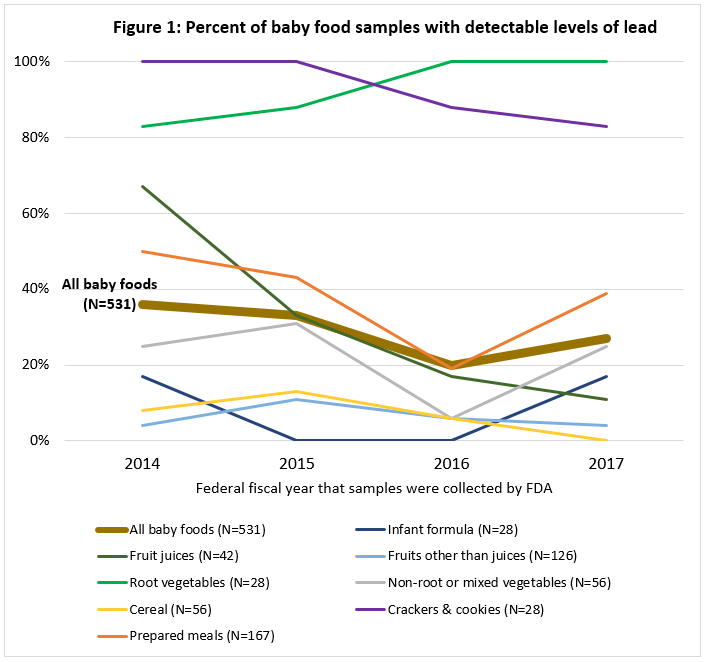

To provide context for the 2017 data, we started by comparing it with the 2014-2016 results. Figure 1 and table 1 below provides the results for more than one hundred baby food samples collected by FDA each year. We grouped them into eight categories, with two categories – prepared meals and fruits (other than juices) – representing more than half of the samples.

Key trends and results from the 2017 data include:

- The downward trend in baby foods indicated by the 2014-2016 samples reversed – with 27% of samples having detectable levels of lead in 2017, up from 20% in the prior year.

- This overall increase in samples with detectable lead in 2017 was largely due to prepared meals, with 39% of the samples having detectable lead levels, up from 19% the prior year. With almost one-third of total baby food samples, the increase in this category more than offset progress in other categories.

- Fruit juices had significant progress steadily dropping from 67% of the samples having detectable lead levels in 2014 to 11% in 2017. We don’t know why the rates dropped but it suggests that substantial improvements are possible.[2]

- One sample of fruit yogurt dessert had 31 parts per billion of lead. A single serving of this product would exceed the agency’s maximum daily intake for lead.

- Baby food root vegetables (carrots and sweet potatoes) and crackers and cookies (teething biscuits and arrowroot cookies) remained stubbornly high at 100% and 83%, respectively, having detectable levels of lead. This continues a four year trend of high detectable lead levels for these categories.

- Cereal and fruit continued to show progress since 2015. In 2017, there were no samples of baby food cereal with detectable lead and only one of 27 baby food fruit samples other than juices had detectable lead.

- One of six samples of infant formula had detectable levels of lead compared to none in the prior two years.

- The increase in non-root and mixed vegetable samples was primarily due to all 2017 mixed vegetable samples having detectable levels – although we don’t know the ingredients in the mixed vegetables, based on its unusually high percent detections, it’s likely that carrots may have contributed to the increase.

Table 1: Percent of samples with detectable levels of lead of baby food

| Category | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | All 4 Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All baby foods (N=531) | 36% | 33% | 20% | 27% | 29% |

| Infant formula (N=28) | 17% | 0% | 0% | 17% | 7% |

| Fruits juices (N=42) | 67% | 33% | 17% | 11% | 31% |

| Fruits other than juices (N=126) | 4% | 11% | 6% | 4% | 6% |

| Root vegetables (N=28) | 83% | 88% | 100% | 100% | 93% |

| Non-root or mixed vegetables (N=56) | 25% | 31% | 6% | 25% | 21% |

| Cereal (N=56) | 8% | 13% | 6% | 0% | 7% |

| Crackers & cookies (N=28) | 100% | 100% | 88% | 83% | 93% |

| Prepared meals (N=167) | 50% | 43% | 19% | 39% | 37% |

| Non-baby foods (N=3,272) | 30% | 33% | 19% | 22% | 26% |

Comparison of baby and regular food products for ten key ingredients

Focusing on products marketed as baby food tells only part of the story. Parents often make or prepare food for their infants and toddlers. Therefore, we explored how baby foods compared with ingredients parents might use to make food at home.

We identified ten fruit and vegetable ingredients (processed and fresh) that FDA had collected from 2014-2017 that consisted of a single food type and had an option marketed as baby food. Table 2 below provides the percentage of samples with detectable lead in the products associated with those ingredients. Key observations about the ten ingredients include:

- Canned fruit: FDA did not test any canned baby food. However, as we examined the data, we noticed that 83 of 84 samples (99%) of canned fruit (apricot, peach, pear, pineapple and fruit cocktail) had detectable lead. By comparison, only one of 31 fresh or frozen samples of peach, pear and pineapple had detectable lead. All canned sweet potatoes had detectable lead as did baby food sweet potato purees. In contrast, other canned products such as beets, beans, corn, tuna and soup had much lower rates (ranging from 14 to 36%). Chili con carne and clam chowder had 64% and 79% respectively. These results suggest that the canning process or can manufacturing may be a source of lead, especially for fruits.

- Vegetables

- Sweet potatoes: All baby food and canned sweet potatoes had detectable lead. The one sample of peeled and baked sweet potatoes had no detectable lead – which could suggest the preparation method removes lead – though more samples would be needed to confirm a pattern.

- Carrots: Lead was detected in 12 of 14 samples (86%) of baby food carrot puree. In contrast, the rates were lower in fresh carrots (which FDA peels and boils before testing) at three of 14 samples (21%) and baby carrots (which come peeled and cut) at one of 14 samples (7%).

- Green beans: Lead was found in processed green beans but at lower rates than carrots and sweet potatoes: baby food puree (1 of 14 samples or 7%); canned (2 of 14 samples or 14%); and none of fresh or frozen (which were boiled before testing).

- Squash: Lead was found in about one-third of squash samples: baby food puree (5 of 14 samples or 36%) and boiled fresh or frozen squash (10 of 30 samples or 33%) with winter squash having twice the number of samples with lead as summer squash.

- Peas: Lead was found at rates similar to green beans and squash: baby food puree (1 of 14 samples or 7%) and none of fresh or frozen that were boiled.

- Fruit

- Apples: Half of bottled apple juice had lead (7 of 14 samples). In contrast, the other apple products had lower rates: baby food puree and applesauce each at 1 of 14 samples (7%) and unpeeled raw apples at the same rate.

- Bananas: No lead detected in 29 samples.

- Pears: Lead was found in all of the canned pears with lower rates in other pear products: baby food juice (4 of 14 samples at 29%), unpeeled raw pears (1 of 14 samples at 7%) and none in baby food puree.

- Peaches: Lead was found in all of the canned peaches with lower rates in the baby food puree (2 of 14 or 14%) and none in raw or frozen.

- Grapes: Lead was commonly found in all types of products of grapes with all raisins having detectable levels. Juice made from concentrate has 12 of 14 samples (86%) with lead. Baby food juice has 8 of 14 samples (57%) with lead. Raw red or green grapes had 6 of 15 samples (40%) with lead.

Table 2: Comparison of ten fruit and vegetable products (processed and fresh) that were selected because they primarily consisted of a single food type and had a baby food option.

| Sampling Results 2014-2017 | % Detects | # Detects |

|---|---|---|

| Sweet potatoes (18% of veg. in infant diet) | 97% | 28 of 29 |

| Baby food puree | 100% | 14 of 14 |

| Canned | 100% | 14 of 14 |

| Baked and peel removed | 0% | 0 of 1 |

| Carrots (13% of veg. in infant diet) | 37% | 16 of 43 |

| Baby food puree | 86% | 12 of 14 |

| Fresh, peeled, and boiled | 21% | 3 of 14 |

| Baby carrot | 7% | 1 of 15 |

| Green beans (13% of veg. in infant diet) | 7% | 3 of 43 |

| Baby food puree | 7% | 1 of 14 |

| Canned | 14% | 2 of 14 |

| Fresh/frozen, boiled | 0% | 0 of 15 |

| Squash (11% of veg. in infant diet) | 34% | 15 of 44 |

| Baby food puree | 36% | 5 of 14 |

| Winter, fresh/frozen, boiled | 47% | 7 of 15 |

| Summer, fresh/frozen, boiled | 20% | 3 of 15 |

| Peas (4% of veg. in infant diet) | 4% | 1 of 28 |

| Baby food puree | 7% | 1 of 14 |

| Green, frozen or boiled | 0% | 0 of 14 |

| Apples (31% of fruit in infant diet) | 18% | 10 of 57 |

| Baby food applesauce | 7% | 1 of 14 |

| Baby food juice | 7% | 1 of 14 |

| Raw with peel (red) | 7% | 1 of 15 |

| Bottled applesauce | 0% | 0 of 14 |

| Bottled apple juice | 50% | 7 of 14 |

| Bananas (21% of fruit in infant diet) | 0% | 0 of 29 |

| Baby food puree | 0% | 0 of 14 |

| Raw | 0% | 0 of 15 |

| Pears (13% of fruit in infant diet) | 33% | 19 of 57 |

| Baby food puree | 0% | 0 of 14 |

| Baby food juice | 29% | 4 of 14 |

| Raw with peel | 7% | 1 of 15 |

| Canned in light syrup | 100% | 14 of 14 |

| Peaches | 37% | 16 of 43 |

| Baby food puree | 14% | 2 of 14 |

| Canned in light/medium syrup | 100% | 14 of 14 |

| Raw or frozen | 0% | 0 of 15 |

| Grapes | 70% | 40 of 57 |

| Baby food juice | 57% | 8 of 14 |

| Red or green raw | 40% | 6 of 15 |

| Juice, frozen conc., reconstituted | 86% | 12 of 14 |

| Raisins | 100% | 14 of 14 |

| Percentage of ingredient in infant diet is based on 2018 study authored by Callen et al for infants 6 to 8.9 months old and products marketed as baby food. | ||

Renewed action needed to drive down lead in food

Earlier this year, we used an FDA study analyzing its 2014-2016 data to estimate that 2.2 million children exceed the agency’s maximum daily intake for lead. In light of that estimate and the results of the 2017 testing, it is critical to strengthen efforts to reduce lead contamination in the diet, especially in foods that young children commonly eat.

We need more information on the most effective methods to reduce lead contamination. Industry should work to adopt these practices. Important areas for progress include identifying more effective washing and peeling methods and better understanding why lead is so common in the canned version of fruits and sweet potatoes. Testing food is an important step to identify problem foods; however, without a systematic management of the supply chain, from farm to fork, progress may not come fast enough.

[1] In the TSDS, FDA staff purchase samples from three different cities in a region. The agency then mixes those samples together for a composite sample that is tested. In this blog, when we refer to sample, we mean the composite sample for the region.

[2] Although a very positive development, the benefits to children may be limited since the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends no fruit juice for children under one year and then only a small amount in later years.