[pullquote]Preliminary testing results: 50% (7 of 14) of water heater tanks tested in child care centers had levels over 50 ppb with one at 2,680 ppb. For all but one of these, flushing through the tank drain significantly reduced the lead levels in the water heater. At the hot water tap, only 4 of 161 (2%) samples were above EDF’s action level (3.8 ppb). Water heaters may function as “lead traps,” but more investigation is needed. Best to avoid using hot water for cooking or drinking.[/pullquote]

Tom Neltner, J.D., is Chemicals Policy Director. Analysis conducted by Lindsay McCormick, Project Manager.

Last March, I was giving a talk on lead and drinking water at the National Lead and Healthy Housing Conference. A questioner from a state health department asked me why the standard lead testing methods only sample cold water when experience suggests that people use hot water when making infant formula, dissolving powered drinks, and cooking food. After mumbling for a few minutes that people are supposed to drink cold water, I realized that I really didn’t know the answer – but should.

When risk assessment ignores real life, we are bound to miss something important. For hot water, I think we may be.

Hot water is likely to leach more lead from solder and brass than cold water. EPA makes this clear in its model public education and consumer notices for public water systems which state:

Use cold water for cooking and preparing baby formula. Do not cook with or drink water from the hot water tap; lead dissolves more easily into hot water. Do not use water from the hot water tap to make baby formula.

In addition, if the water comes through a lead pipe, it may contain particles of lead if the pipe is disturbed. The most common example of this situation occurs with a lead service line (LSL) – which connects the drinking water main under the street to the building – is disturbed. The lead particulate from the service line likely settles and accumulates at the bottom of the hot water tank where high temperatures from the flame or electric heater coil may dissolve the lead into the water. The settled particulate could also be re-suspended when water flow is high.

This issue became evident in an ongoing EDF pilot project to comprehensively evaluate and reduce lead in drinking water at child care centers. As part of this pilot, we are measuring lead levels in water taken from all faucets. To explore this concern of lead in hot water, we also included hot water samples from the faucets used for drinking water and directly from the drain valve of the water heater (see photo). After letting the water stagnate overnight to provide us with a worst case sample, our partners in Chicago, Illinois; Grand Rapids, Michigan; Cincinnati, Ohio; and Starkville and Tunica, Mississippi sampled the first ¼ liter of hot water at the faucets commonly used for drinking water. They also collected two consecutive ¼ liter samples from the drain of the hot water heater tank after flushing the line for five seconds. See the full protocol here.

This issue became evident in an ongoing EDF pilot project to comprehensively evaluate and reduce lead in drinking water at child care centers. As part of this pilot, we are measuring lead levels in water taken from all faucets. To explore this concern of lead in hot water, we also included hot water samples from the faucets used for drinking water and directly from the drain valve of the water heater (see photo). After letting the water stagnate overnight to provide us with a worst case sample, our partners in Chicago, Illinois; Grand Rapids, Michigan; Cincinnati, Ohio; and Starkville and Tunica, Mississippi sampled the first ¼ liter of hot water at the faucets commonly used for drinking water. They also collected two consecutive ¼ liter samples from the drain of the hot water heater tank after flushing the line for five seconds. See the full protocol here.

Overall, we were encouraged to find relatively low levels of lead in most faucets tested in the child care centers. After testing hot water at 161 faucets in 11 child care centers, we have only found lead levels over EDF’s action level of 3.8 ppb in 4 of the first draw samples (2% sampled). The vast majority of hot water samples (83%) had non-detectible lead concentrations.

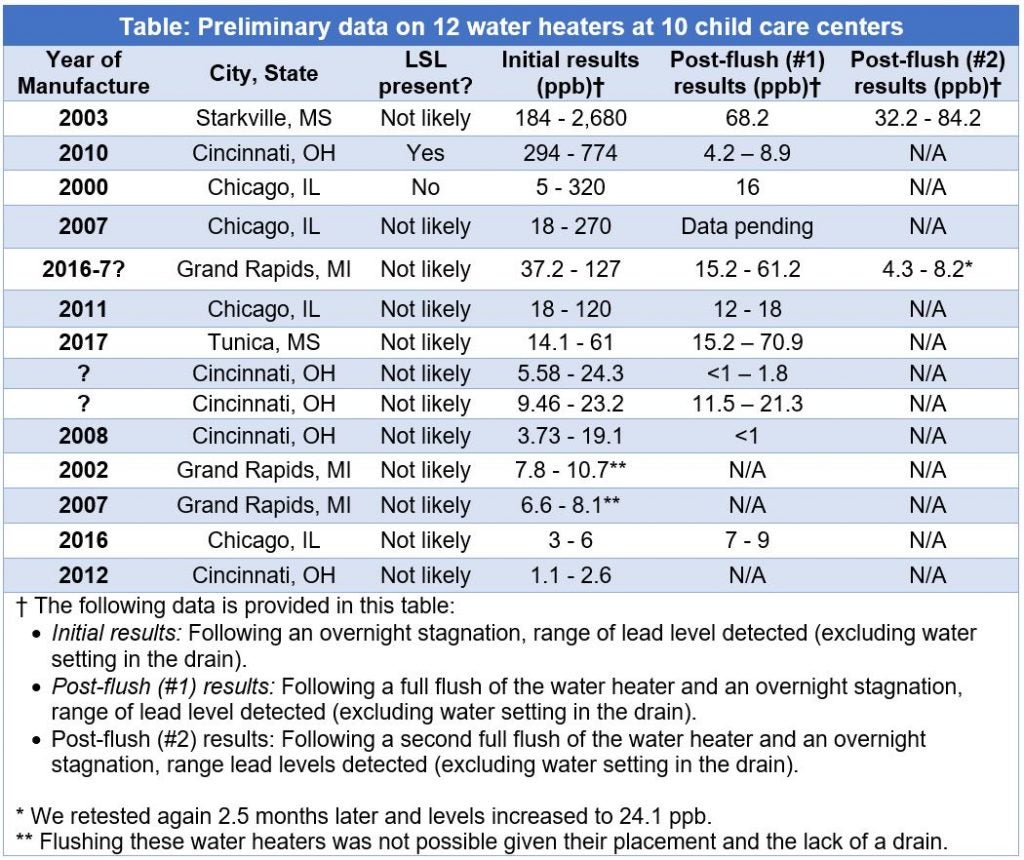

However, the lead levels in samples taken from hot water heaters are alarmingly high, with 7 of 14 water heaters tested having at least one sample with lead levels above 50 ppb. See Figure 1 and Table 1 below. One water heater had levels as high as 2,680 ppb. The initial samples from the water heater often were discolored – some even like a sludge.

Despite still being in the middle of the project, we are choosing to share the results of what we are seeing, and we will keep you informed as we get further results.

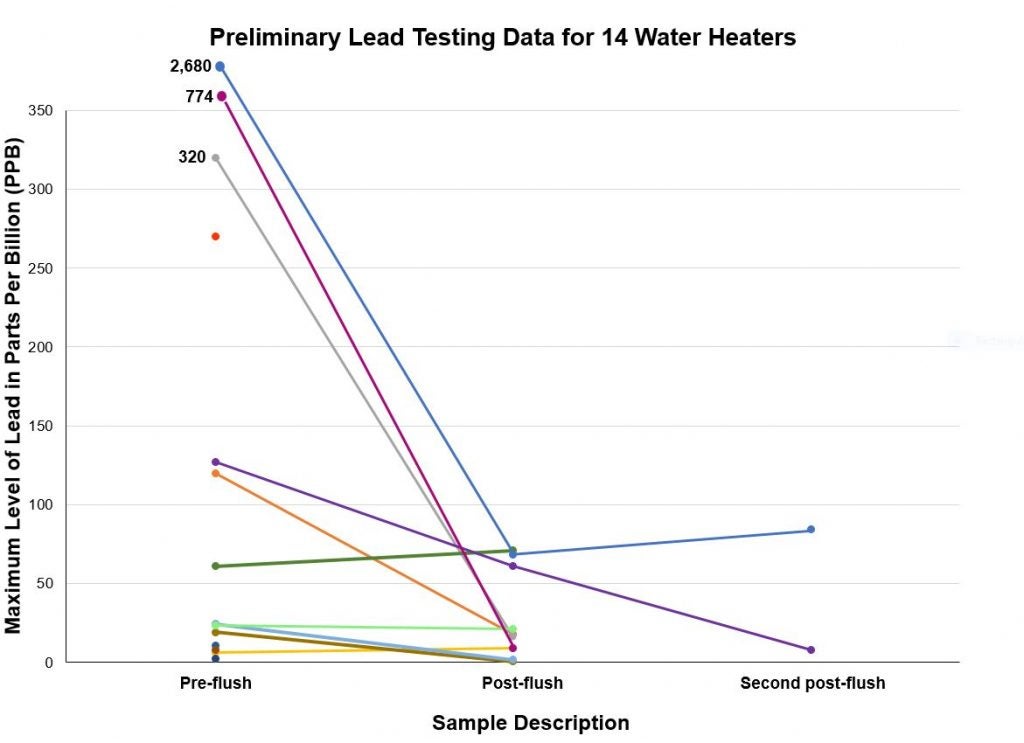

Figure 1: Measured lead levels in ¼ liter of water drained from 14 hot water heaters in 11 child care centers. Highest lead level detected during each sampling phase – the initial sampling (pre-flush), following a full flush of the water heater (post-flush), and following a second flush of the water heater (second post-flush). Lines connect data for a single water heater.

Our partners performed sustained flushes through the drain on 10 water heater tanks. The flushing helped significantly in almost every case. Among water heaters where water levels first tested above 50 ppb, flushing dropped the lead levels on average from 456 ppb to 20 ppb.[1] When levels in the water heater initially tested below 50 ppb, the drop was less evident (from 17 ppb pre-flush to 13 ppb post-flush, on average). Our partners performed second flushes with mixed results in two cases in an attempt to further reduce the lead levels. See additional detail in Figure 1 above and Table 2 below.

Our project is ongoing. So far, our takeaways are:

- Water heaters may be functioning as “lead traps” for upstream sources of lead.

- Don’t use hot water for preparing baby formula, drinking, or cooking. EPA’s advice is still sound. A good alternative is an electric hot water kettle.

- Flush your water heater through the drain line regularly per manufacturer’s instructions. This will reduce the accumulated sediment and should extend the life of your water heater and improve its overall energy efficiency.

Stay tuned as we learn more and please share with me any test results you find. We need to learn from each other.

[1] One child care center had an LSL, which we replaced with our partners in Cincinnati – Greater Cincinnati Water Works and People Working Cooperatively. Before replacement, the water heater had a baseline reading of 393 ppb (data not shown). One week following replacement, two consecutive samples from the water heater were 296 ppb and 774 ppb. Following a full flush of the water heater, levels dropped down to below 10 ppb.