A new report from the Academy of Medicine, Engineering and Science of Texas (TAMEST) is shedding more light on what we know and don’t know about the potential health and environmental impacts caused by oil and gas development in Texas.

The report, the first of-its-kind authored by experts across the state, looks at all areas of concern related to oil and gas – including seismicity, air pollution, land and traffic issues – but TAMEST’s observations about the risks to water are especially noteworthy.

Tracking and reducing spills and leaks

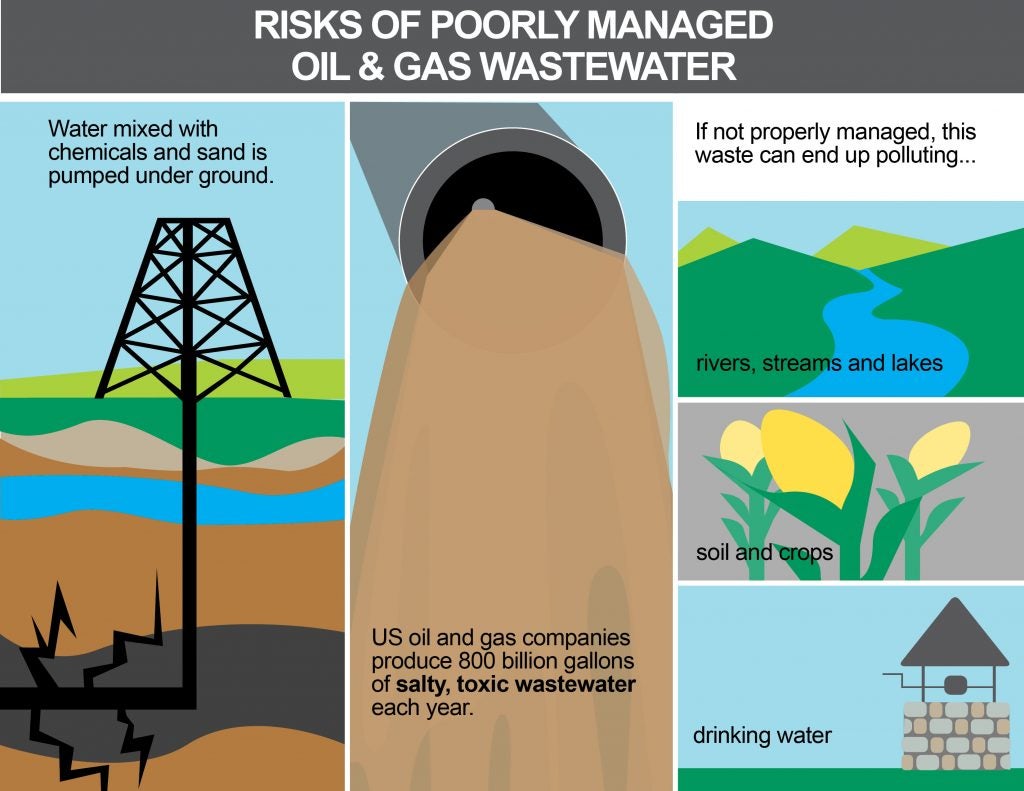

Wastewater that comes out of an oil or gas well is usually extremely salty and can be laden with chemicals, and TAMEST notes this wastewater can contaminate soil and harm vegetation. In fact, according to the report, spilling or leaking wastewater and other substances is the most likely pathway for surface water contamination from oil and gas development in Texas. Yet Texas is the only major state that doesn’t require companies to report their produced water spills. The report suggests that Texas should consider improving spill reporting policies in order to better understand where spills are happening, and what is causing them.

The report also suggests spills can be reduced through better management of the fluids at or near the surface of a well, and asserts that regulators and industry should focus on reducing the risks of well leakage through improved well design and construction.

Managing the strain on freshwater, without causing more environmental problems

TAMEST also looks at the way industry uses water more generally. According to the report, less than 1% of the state’s freshwater is used for hydraulic fracturing, although in some rural and arid counties, as much as 90% of the local freshwater is used for oil and gas development. This can put a strain on communities where access to fresh water is scarce.

Water scarcity is driving debate about whether or not companies should drill wells with brackish (salty) water, or use their own wastewater, rather than freshwater. This practice could help alleviate water scarcity concerns. However, as TAMEST notes, the use of these alternative resources “increases the potential for spills or leaks that could lead to further environmental impacts.”

Therefore, while TAMEST notes that increased use of fresh water alternatives for oil and gas operations is desirable, the authors also recommend expanded research to understand the potential environmental trade-offs of increasing this practice.

A growing consensus to keep industry wastewater in the oilfields

The experts don’t expect the interest in reusing produced water to expand outside the oilfield (like using it for agricultural purposes) any time soon. TAMEST notes that most water from Texas oil and gas wells is “extremely poor quality” and neither the science — nor the technology — currently exist to safely or affordably treat this wastewater for use in other purposes.

According to the report, “In Texas, both economics and risk considerations dictate that much of the produced water will continue to be injected in deep wells or used as fracturing fluid to minimize impacts on other water sources.”

The TAMEST report goes further, saying there are “potential negative impacts of trace contaminants in produced water that might limit their beneficial use” outside the oilfield.

This reinforcement — that economic and risk realities mean that reuse of oil and gas wastewater is best limited to within the oilfield — aligns with EDF’s own science-based position. There are too many knowledge gaps about the toxicity of produced water chemicals to effectively design treatment systems or conduct risk assessments. Meaning we don’t currently have the ability to design effective environmental and public health policies to protect communities from exposure to this wastewater.

Oklahoma came to a similar conclusion earlier this summer. The state’s Produced Water Working Group analyzed numerous produced water management alternatives for nearly a year and concluded that the most economically and environmentally viable near-term alternative is in-field recycling and agreed that in-depth research on other reuse alternatives, including improved understanding of toxicological risks, is necessary before pursued.

There’s no doubt that water management in the oilfield can and should be improved. Risks to fresh water resources from drought and heavily localized water use are real, and communities across the state have experienced them. But that doesn’t mean that we need to rush to alternatives that we don’t fully understand or encourage practices that create new risks to our health or environment.

The record is clear that oil and gas development can and does pose a real risk to water resources. With this report Texas experts reaffirm the realities of these potential impacts, but also join a growing chorus of voices in encouraging smarter, science-based policies and practices that aim to find a balance in the way industry and regulators address water management challenges without jeopardizing our water resources, health, and environment.