Demand Response at the Core of Energy Savings for Large Office Building in Chicago

By: Karan Gupta, EDF Climate Corps Fellow at Jones Lang Lasalle

Demand response – an energy saving tool that encourages customers to shift their electricity use to times of day when there is less demand on the power grid or when more renewable energy is abundant – has been at the core of my work this summer as an Environmental Defense Fund Climate Corps fellow. My host company, Jones Lang Lasalle, is the property manager for 77 West Wacker Drive, a 50-story office building in downtown Chicago. Here, I am focusing on maximizing the benefits of demand response, which have already been implemented through multiple technologies.

Currently, 77 West Wacker is enrolled in the PJM demand response capacity market through a demand response service provider. As discussed in my previous post, there are standby payments for demand response commitments, meaning that the building is paid for simply making itself available to reduce energy demand when called upon to do so. In addition to these standby payments, the building is paid for actual energy conservation as real demand falls below baseline demand during emergency events. The building also participates in voluntary price-based demand response, whereby energy conservation is performed in non-emergency events to take advantage of opportunities when real-time energy prices exceed the fixed rate that the building pays for energy.

The software platform provided by the demand response service provider allows engineers to view the building’s baseline demand, real-time action alerts and forecasts for weather and energy prices. When the grid is stressed due to extreme weather or system lapses, the engineers receive notification, usually the day of, to enact demand response protocols. While extreme weather may or may not result in an emergency event, it almost always presents earnings opportunities through economic demand response. For this reason, the team here is proactive and monitors weather forecasts throughout the Midwest and East Coast, and has usually already taken action by the time emergency notification is received. In the summer, the primary form of action is “load shifting,” a process works by pre-cooling the building during early morning off-peak hours and reducing cooling demand during peak hours.

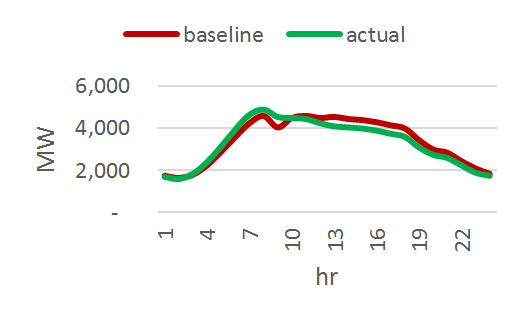

The snapshot above shows a hypothetical demand response event where load shifting was used. The red line represents the baseline and the green line represents actual building use. Actual use exceeded the baseline in the morning hours when building equipment ramped up to pre-cool the building (there is no penalty for going above the baseline during non-peak hours), and then around 10:00am, the equipment ramped down for the rest of the day as it had to work less hard to maintain the lower temperature. During the period where the green line is below the red line, real-time energy prices are paid back to the building for the difference between baseline energy consumption and actual consumption.

When a non-weather event occurs, load shifting may not be an option, and instead a series of minor operational adjustments must be made to achieve the necessary reductions. Tenant comfort is an important consideration when making these adjustments as reasonable temperatures and minimum levels of ventilation have to be maintained. Excessive ramping and cycling of equipment should also be avoided to prevent undue stress and shortened life. Where base building equipment adjustments alone are not sufficient, the building may send out notices for tenant involvement. Effective communication is critical for tenant satisfaction, but to that end, building management has performed exceedingly well, making efforts to educate occupants about the value of demand response.

The two primary technologies that have enabled demand response capability at 77 West Wacker are the building automation system (BAS) and variable frequency drives (VFDs). The building automation system allows for monitoring and control of the various equipment from a central command center (which I’m pictured standing in above). This control is necessary to quickly enact demand response protocols while guarding the health, safety, and comfort of the building occupants. In the past, motor-driven equipment such as fans and pumps would either run at full load or not at all, and when at full load, would be modulated by dampers or fans. A common analogy is using the brakes to control the speed of a car while pushing the accelerator to the limit. VFDs basically provide throttle control and allow for the modulation of such equipment.

The next step in fully implementing demand response at 77 West Wacker is enrolling into ancillary services, which are used to support the transmission of electric power from seller to purchaser (i.e. scheduling and dispatch, electric grid protection, etc.). While BAS and VFDs are a strong first step, further hardware and software investments will be necessary to make frequency regulation possible. To some extent, real-time control will have to be relinquished to the system operator, but the primary objective will still remain to maintain tenant satisfaction. Automated scripts that guide operational parameters within predefined limits will occasionally have to override signals to ramp loads up or down. Cracking the code for successful implementation will hopefully release a new wave of revenue for property managers around the country while enhancing grid reliability.

This post originally appeared on the EDF Climate Corps Blog.