After a year-long delay from the pandemic, COP26 — the next UN meeting aimed at accelerating global action on climate change — is right around the corner. As a newly rejoined Party to the Paris Agreement under the leadership of President Biden, the United States will be arriving under much different circumstances than the last COP. But will other countries see the U.S. participation and its new commitments as credible? Will the United States be positioned to push global ambition to the levels needed to beat the climate crisis? The answers to those critical questions depend on how much policy progress the U.S. can make at home.

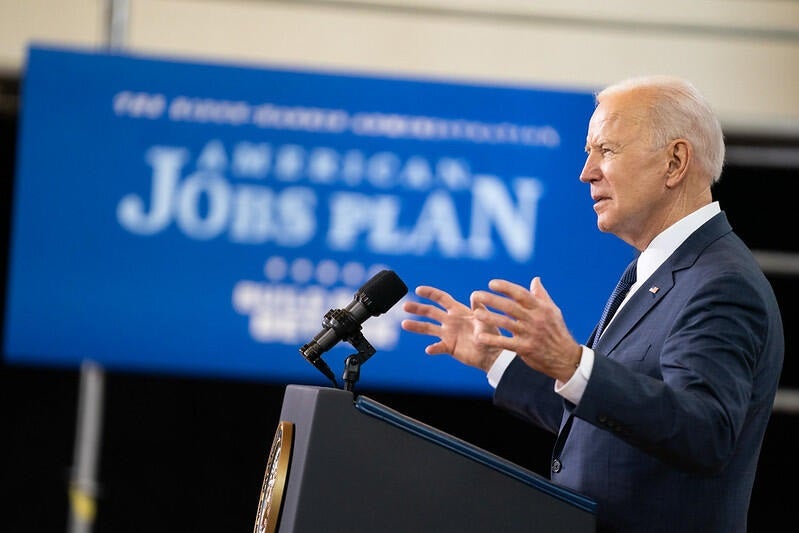

In April, the United States renewed its commitment to meeting global climate targets, including through an ambitious new nationally determined contribution (NDC) that pledges to reduce U.S. emissions by 50-52% from 2005 levels by 2030. While highly ambitious, multiple analyses have demonstrated that this goal is also achievable, lending much-needed credibility to the U.S. pledge. Since then, the Biden administration has unveiled a series of actions intended to move the country towards achieving that goal.

Critically, one of the largest and most significant components of the president’s plan to tackle climate change is a piece of legislation that is currently in active stages of negotiation in Congress. Getting this bill and the included climate investments across the finish line will be crucial to meeting our climate goals. On top of that, the U.S. must also ratchet up regulatory climate action at the federal and state level to meet our 2030 pledge, as incentives and investments alone won’t be enough to slash emissions at the pace and scale needed.

So what has the U.S. accomplished since announcing its new NDC in April and what is still on the table? Here is where progress stands.

Congress is on the verge of groundbreaking climate progress

An important element of the U.S. strategy for combating climate change is a sweeping climate and economic recovery bill known as the Build Back Better Act. With dozens of critical climate and clean energy investments, the Build Back Better Act would be the single largest investment in climate action ever made by the U.S. government and would make significant progress toward the country’s goal to slash climate pollution in half by 2030.

The bill includes historic investments in clean electricity generation, vehicle electrification, climate smart forestry and agriculture, and a fee on the super-potent greenhouse gas methane. Getting these investments into the pipeline will help us make immediate progress toward curbing climate pollution, while putting us on the path toward meeting our 2030 and 2050 climate goals. Our analysis finds that these investments will also have substantial benefits for job creation, economic development, environmental justice and equity, and public health.

But these benefits are not yet assured. Congress has not yet come to an agreement to pass these critical investments, and both the overall size of the package and its individual components remain in flux. There’s a lot on the line — the fate of the Build Back Better Act will likely strongly influence the ability of the U.S. to meet its 2030 NDC, which will in turn influence President Biden’s ability to advocate at COP26 and beyond for increased global action on climate change.

To learn more about the Build Back Better Act and follow along as the process unfolds, tune in for regular updates here.

White House takes aim at climate pollution from multiple sources

Even as Congress debates the Build Back Better Act, President Biden has been busy moving forward with additional actions to reduce climate pollution from a variety of sources.

Methane: In September, the White House, together with the European Union, announced the launch of a new global goal to reduce methane emissions by 30% by 2030. Methane is a super potent greenhouse gas with roughly 80 times the warming potential of carbon dioxide in the near-term, so curbing methane pollution is especially critical for slowing the rate of warming.

Domestic methane regulations are also in the works, with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) expected soon to issue new proposed rules to tighten pollution protections for oil and gas wells. In doing so, the EPA has an important opportunity to adopt protective standards that strengthen leak detection and repair requirements, incorporate advanced monitoring technologies and other best practices that leading states and operators have already deployed.

HFCs: Also in September, the White House unveiled a new regulation aimed at phasing down a class of powerful greenhouse gases known as hydrofluorocarbons or HFCs, which are commonly used in air conditioning and refrigeration. The new rule from the EPA is expected to reduce this potent form of climate pollution by 85% over the next 15 years. According to the White House, that will be the equivalent of eliminating 4.5 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide by 2050, or about three years’ worth of climate pollution from the electricity sector.

Pollution from transportation: In August, the President issued a historic executive order directing EPA to move forward with actions that would substantially reduce climate and health-harming pollution from the transportation sector. The order directs EPA to issue longer term, multi-pollutant emissions standards for passenger cars and sets an ambitious new target to make half of all new vehicles sold in 2030 zero-emissions vehicles. The order also directs EPA to issue rules to reduce harmful climate and air pollution from large freight trucks and buses — including direction to evaluate the role that zero-emissions vehicles can play in swiftly reducing pollution from those sources.

Biden moves to deliver on climate finance commitments

The Biden administration is also moving forward with plans to increase financial aid to developing nations. President Biden has said he would seek Congressional support to double international climate aid to $11.4 billion a year by 2024. Securing this funding will be key for demonstrating to our global partners that the United States is serious about supporting low-carbon growth and climate adaptation throughout the world. Recently, developing nations have expressed increasing frustration at wealthier nations for failing to live up to previous financial aid commitments.

U.S. states need to move from pledges to policy to close the emissions gap

The more than two dozen U.S. states that have made climate commitments in line with the Paris Agreement also have an important role to play in driving down U.S. emissions, but they are largely falling short. A December 2020 report found that these states were not on track to achieve critical 2025 and 2030 emissions goals.

This past year, however, a few states made noteworthy forward momentum: Washington state passed the nation’s most ambitious limit on climate pollution this past spring, providing a model for other states to follow. Pennsylvania, one of the biggest emitters in the country, is nearing the finish line on joining a multi-state program to cap pollution from power plants. And Illinois just passed a clean energy law that will phase out all fossil fuel plants by 2045.

On the other hand, most states with climate goals have much more work ahead to move from pledges to policy, including New Mexico, Oregon and Colorado.

The world is watching to see what the U.S. can deliver

As a global economic superpower and the largest historical polluter, the U.S. has a unique and important role to play in confronting the climate crisis. Our actions have an outsize impact and stand to influence the commitments of others. The health and economic upsides, at home and abroad, will be enormous — if we seize them.

That’s why it’s time for Congress to go bold with climate legislation. What gets passed from Capitol Hill in these coming weeks will not only impact the lives of Americans around the country; it will help put the U.S. in an even stronger position to support the goals of the Paris Agreement.