The transformative power of three days on a river

The history of California water is saturated with stories about years-long battles that inevitably get called “water wars.” But UC Merced is trying to flip that narrative and chart a new course for water in California based on finding common ground, or in this case, finding common water.

“Finding Common Water” is the name of a river trip that UC Merced and EDF have organized to bring together individuals who often hold diverse perspectives. The goal is to find areas of alignment and explore new collaborations.

I joined the inaugural “Finding Common Water” river trip that EDF and UC Merced co-hosted in 2022, and returned this summer for another unforgettable experience organized by Josh Viers and Lauren Parker of UC Merced’s Secure Water Future Program and financially supported by EDF and the State Water Contractors. Our diverse cast of rafters came from state and federal water agencies, a local water district, a Tribe, environmental and rural community nonprofits, and agriculture.

At a time when there is so much chaos and uncertainty in the world, getting out and spending three days along a secluded stretch of the Tuolumne with this fascinating group did wonders for the soul. As Josh said at the end of the tour, “Three days on the river buys me 300 more days off the river.”

Not only were we surrounded by the beauty of this majestic area, but our time together re-enforced in me the power and potential for collaboration on thorny and often protracted water issues and left me feeling hopeful for the future. To better convey the transformative power of the experience, I’d like to share the perspectives of four participants.

Yourself first, organization second

Participants were instructed to come to the trip as individuals — yourself first — rather than representatives of where they work — your workplace second.

Austin Stevenot, director of Tribal engagement at River Partners and a member of the Northern Sierra Mewuk Tribe, saw the value of those instructions, though he acknowledged it was a challenge for him because being Mewuk is so core to his identity.

“When you strip away someone’s pride and status, it makes us humans without the power of our title. That makes people vulnerable, and it makes it easier to have a conversation,” Austin said. Being on the river also helped separate people from their work affiliations: “You quickly realize the river doesn’t care what you do, or who you are. You are just another person.”

The trip spurred Austin to connect more deeply with others who he suspects had never really talked one-on-one with someone from a Tribe. One conversation that stood out was with Chandra Chilmakuri, the assistant general manager for water policy for the State Water Contractors, an association of 27 public water agencies that work to provide water to over 27 million Californians and 750,000 acres of farmland. Austin and Chandra discovered some similar views on the environment and water among people from North American Indian people and people from India, where Chandra is from. Both said they hope to continue their conversation beyond the trip.

At the end of our excursion, every participant had to make one commitment. Austin’s commitment: To bring more Tribal people on a future river trip.

“Water has been diverted and shifted around this state without consideration of certain people and with very little consideration of our environment,” he said. “Tribes in California were never given any water rights.

“We need to do this trip with some policymakers and invite Tribal water people and get them together so the policymakers can really hear the Tribal story and see how important it is for Tribes to be involved in water.”

Building relationships to find the right balance

Chandra, who has 20 years of experience as a water resources engineer, also called out his conversation with Austin as a trip highlight. “On the first day, Austin had very strong opinions on water issues in the state. He said some powerful things about Tribes,” Chandra said. “While I don’t necessarily agree with everything, I feel like we all have to figure out how to address what Tribes need. That conversation with him definitely stuck with me.”

Another thing that stuck with Chandra was how passionate everyone was about trying to solve California’s water problems, which he boiled down to balancing many different needs. “At the end of the day, we may have different perspectives on the balance, but everyone understands there needs to be a balance.”

His hope is that the honest conversations on the river will help start building relationships where people can talk freely about their positions, gain a better understanding of another side’s position and ultimately reduce adversarial positions.

Turning the tide toward collaboration

Jessi Snyder, program director for community development at Self-Help Enterprises, helps small rural drinking water and wastewater systems get funding to improve their systems. The tiny rural communities who rely on those systems have access to more financial resources than in the past, she said, but still don’t have any power to this day. However, the trip was wonderful because it reminded her about how widespread a collaborative mindset has become and how that might lead to communities having more agency when it comes to water. “The collaborative mindset might not dominate yet, but it feels like the tide is turning,” she said.

The most valuable part of the trip for her was the peer learning and networking, especially with folks from government agencies whose work is less familiar. “I was able to pick a couple people’s brains about an innovative project I’m working on to bring low-cost renewable energy to water systems,” she said.

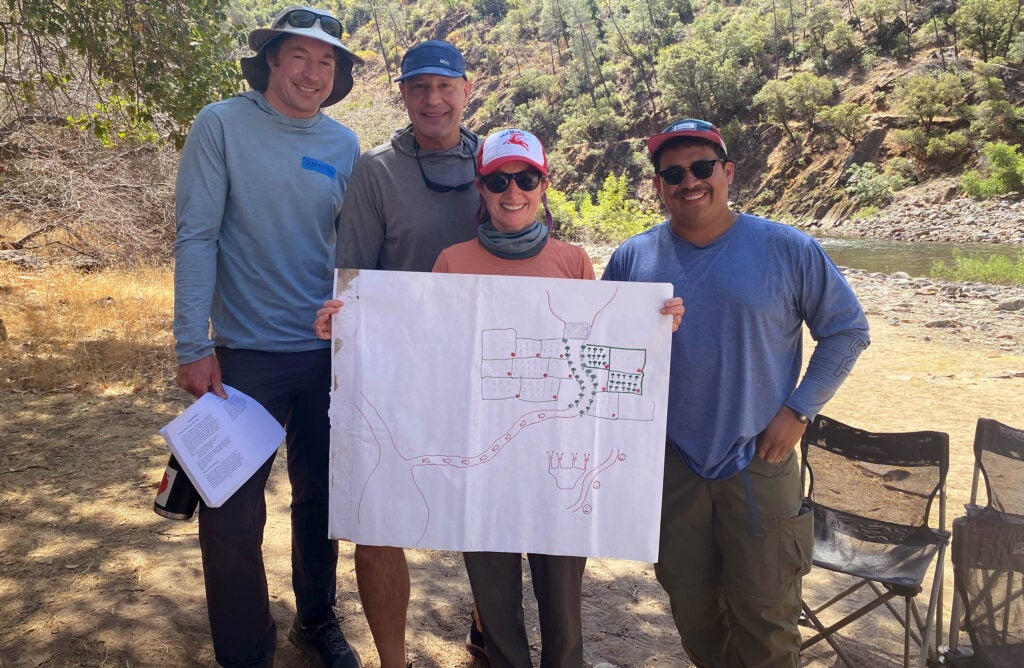

Before the trip, everyone was asked to send the organizers one “bright spot in California water,” and then during the trip the participants broke up into groups to talk about their bright spots and even draw them. Jessi’s group talked about breaking down silos as their bright spot.

“We have come a long way out of our silos, and a lot of people are really invested in thinking collaboratively and coming up with shared solutions with multiple beneficiaries,” she said.

Connecting over the San Joaquin Valley

Gustavo Cruz describes himself as “a proud first generation Mexican-American who did not know what a watershed was until college.” Gustavo took an environmental engineering class taught by Josh at UC Merced in 2016 and is now an associate water resources engineer focused on flood control and water supply planning at the Solano County Water Agency, where he started as an intern nine years ago.

Gustavo highlighted the guidance to come to the trip as yourself first and agency second as “very liberating.” It prompted him to bring up water rights as one thing about California water that is broken.

“The volume of overallocation for the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers in and of itself is problematic,” he said, referring to study co-authored by Josh showing that water right allocations total five times the state’s mean annual runoff. “It creates a situation of haves and have-nots, especially during drought periods.”

Gustavo said another benefit of the trip was getting to know people from nonprofits, like Self-Help Enterprises and Audubon California, and learning about their work in the San Joaquin Valley, where he lived while attending UC Merced.

“The San Joaquin Valley will always be a special place to me,” he said.

“We have changed the fundamental processes in the San Joaquin Valley, and I think there is a lot of great work to find what is sustainable,” he said. “I can’t say I know exactly what a sustainable valley looks like, but meeting people on this trip from federal, state, and local agencies and NGOs, I was overcome with this feeling of optimism. There are people at so many levels that do care about what ‘we’ are doing there.”

The diversity of perspectives was the cause of his optimism, he said. “We came from different backgrounds personally and professionally, but I think there was a lot of common water that allowed us to connect on so many different levels.”