Every lead service line replaced yields an estimated $22,000 in reduced cardiovascular disease deaths

Tom Neltner, J.D. is the Chemicals Policy Director.

See all blogs in our LCR series.

Using publicly available information from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), EDF estimated that fully replacing the 9.3 million lead service lines (LSL) in 11,000 community water systems (CWS)[1] across the country would yield societal benefits of more than $205 billion, or about $22,000 per LSL removed. This estimate is based solely on reducing lead exposure in adults in order to have fewer cardiovascular disease (CVD) deaths over 35 years. It does not include the benefits to children’s brain development.

We submitted our analysis in comments to EPA on its proposed revisions to the Lead and Copper Rule (LCR), the federal regulation that limits lead in drinking water. Given the magnitude of the benefits, we called on the agency to incorporate CVD mortality into its economic analysis and consider strengthening its proposal by requiring full LSL replacement as an integral part of every CWS’s efforts, instead of as a last resort when lead levels get too high.

Heart disease and adult lead exposure – A connection long recognized, but now quantifiable

When it comes to reducing exposure to lead, the focus has been almost entirely on protecting children’s brain development. This makes sense, since disruptions at vulnerable, younger ages can result in a lifetime of harm – you only get one chance at a healthy brain.

But as the National Toxicology Program and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) concluded in 2012 and 2013, adult exposure to lead at levels previously thought safe is associated with cardiovascular disease. The mechanism is understood and the evidence is strong. In 2018, we highlighted an important study by Dr. Bruce Lanphear and others that examined data on more than 14,000 adults and found that an increase of 1 to 6.7 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood was significantly associated with an increase in deaths of 37% for all-causes, 70% for CVD, and 108% for ischemic heart disease.

Recognizing its obligations to fully assess both the costs and the benefits in its rulemakings designed to reduce lead exposure, EPA undertook two important efforts:

- Modelled the impact of reduced exposure to lead on adult blood lead levels and estimated the reductions that would be achieved from its October 2019 proposed revisions to the LCR.[2]

- Assessed the scientific evidence and modelled the impact of reduced adult blood lead levels on CVD deaths based on four studies (including Lanphear’s). In June 2019, EPA successfully completed external peer review of the model and posted the reviewer’s comments, its responses to comments and plan to refine the model based on the feedback.

Combining two EPA models to estimate benefits of reduced mortality

With the guidance of experts, we took EPA’s estimate of reduced adult blood lead levels of its proposed rule over 35 years from the first model and applied them to the second model to estimate the reduced CVD deaths from the proposal. We then calculated the societal benefits using EPA’s estimated “value of a statistical life” of $10.2 million in 2016 dollars. For details on the methodology, including assumptions, that we used to calculate the benefits, see our comments on the proposed rule.

Our analysis showed that EPA’s proposal would prevent 3,430 to 6,150 CVD deaths, delivering societal benefits of between $18 and $33 billion over the next 35 years. When added to the IQ benefits, this results in total societal benefits between $26 and $51 billion.

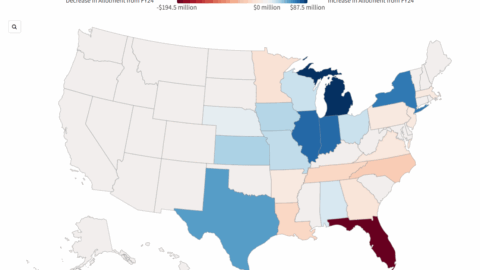

Recognizing that EPA failed to consider the option of requiring all 11,000 CWSs with LSLs to fully replace the 9.3 million lead pipes within ten years,[3] we estimated that the benefits in reduced CVD deaths from this option would be more than $205 billion accrued over 35 years.[4] This is 4 to 8 times more than EPA’s proposal would achieve. Using EPA’s high-end estimated cost[5] to replace an LSL, this would return more than $310 for every $100 invested. See the table below for a summary of our findings.

Estimated societal benefits* of EPA’s proposal and of full LSL replacement in 10 years

| Total CVD benefits** | Total IQ benefits | Total societal benefits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EPA’s Proposal | $18 - $33 B | $7-18 B*** | $26 - 51 B |

| 10-year full LSLR**** | $205 B | Not calculated | >$205 B |

| * Benefits are based on 3% discount. ** Midpoint of high and low estimates based on four studies. See Table 2 of our comments to EPA. ***Based on incremental benefits in Exhibit 6-17 in EPA’s proposed rule for 35 years. **** Based on EPA’s estimate of 9,267,910 LSLs in use on rule’s effective date in 2023. |

|||

Note that our estimates are based on assumptions and rough calculations of publicly available information and do not reflect refinements to EPA’s CVD model that the agency committed to in its June 2019 response to the peer review.

Next steps for EPA

We applaud EPA’s scientists and encourage them to continue their efforts to fully consider the impacts of reduced lead exposure, not only for children’s brain development, but also adult CVD. We recognize that the peer review of the CVD model was not completed in time to be incorporated in its proposed revisions to the LCR.

Given the strength of EPA’s CVD model, especially after the agency refines it as planned, and the magnitude of the expected benefits, we maintain that EPA has an obligation[6] to quantify the CVD benefits and consider revising its proposal to ensure full LSL replacement is an integral part of every CWS’s compliance responsibilities.

The societal benefits are too significant to ignore.

[1] Based on EPA’s estimate of 9,267,910 LSLs in use on rule’s effective date in 2023 and 11,338 CWSs with LSLs. See Exhibits 4-10 and 4-13 in EPA’s Economic Analysis for its proposal.

[2] See EPA’s proposed revisions in Section VI.D.3 in the November 13, 2019, Federal Register at 84 Fed. Reg. 61,727-29. See also Section 6.5 in EPA’s Economic Analysis for the proposal as well as Section D.1 and G in the Appendices to the Analysis.

[3] We used 10 years as a helpful starting point for the assessment. If it takes longer than ten years, it will reduce the benefits.

[4] The estimates for the four studies range from $113 to $296 billion.

[5] EPA, Economic Analysis for the Proposed Lead and Copper Rule Revisions, 2019. See Exhibit 5-11, using the largest estimated cost to replace a LSL.

[6] EPA can address the Proposal’s shortcomings, thereby fulfilling its responsibilities under Executive Order 12898 for Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations, by reducing health disparities, and by helping states and communities that receive federal funding avoid violating Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.