Lead from new “lead-free” brass faucets? An update on progress

Tom Neltner, J.D. is the Chemicals Policy Director and Lindsay McCormick is a Program Manager.

[Update: On 10/23/19, the NSF committee responsible for revising NSF 61 tentatively agreed to tighten the limits on lead leaching from new faucets and drinking fountains. The committee will move forward with a formal vote and, if approved, will receive public comment on the proposed changes.]

Last year, we discovered and reported in a blog, that some new brass faucets that meet existing standards and are labelled “lead-free” can still leach significant amounts of lead into water in the first few weeks of use. Here, we answer some questions that have come up and provide an update on efforts to revise the NSF/ANSI 61 standard to better protect and inform consumers.

Last November, the committee responsible for revising the NSF/ANSI 61 standard convened a group to consider an optional certification for faucets that meet a more protective limit. A study of more than 500 models of faucets showed that 73% of faucets leach less lead into water and can meet a limit that is five times more protective for children. However, currently there is no easy way to identify these “lower lead” models. The optional certification would enable consumers, schools, and child care facilities to identify and purchase faucets that leach less lead to drinking water.

Unfortunately, as described later in this blog, representatives of the brass faucet manufacturers have worked to block the optional certification. As of August 2019, the committee has not decided whether to move forward with a proposal for the optional certification to receive public notice and comment. If the committee fails to move forward, we anticipate that some major retailers that sell brass faucets and other major buyers such as school districts and builders would use their leverage to set higher standards in their purchasing specification that favors models performing better on the NSF/ANSI 61 lead leaching test.

Key questions that have been raised

What is the “lead-free” standard? Most states require that any device or plumbing component that contacts drinking water meet the NSF/ANSI 61 standard, a voluntary consensus standard developed by the Joint Committee for Drinking Water Additives – System Components (“Joint Committee”), that is associated with NSF International. As of 2014, this standard expressly allows lead to be added to brass and bronze metals used in faucets, small valves, drinking water fountains, and icemakers and other end-use devices as long as the average amount of lead in the wetted surfaces is less than 0.25%. Before 2014, the devices could have been up to 8% lead. The current standard also limits the average amount of lead leached during the first three weeks of use to less than 5 micrograms (µg) in the water allowed to sit in the device overnight. As confusing as it sounds, a device that meets these limits can currently be labelled “lead-free.” We explain the standard’s lead leaching test protocol in our November 2018 blog.

Why is lead added to brass? Lead is added to brass to make it easier to machine into smooth surfaces for valve seats, threads, and other fittings. Alternatives to lead have had some problems with corrosion in the past. However, researchers at Virginia Tech, including Dr. Marc Edwards, released a study earlier this year showing that bismuth and silicon brass could withstand very corrosive water. So it appears that the technology exists to make truly lead-free plumbing components that do not noticeably compromise performance.

When is lead leaching a significant issue? New plumbing will usually leach the most lead within the first days after installation. The levels drop over the first few weeks of use as the lead on the surface of the plumbing components gets into the water and as a protective coating develops on the leaded-brass from the corrosion control treatment provided by the drinking water supplier (see Figure 1 in November 2018 blog).

As a result, anyone drinking the water from the brass faucet in the first few weeks may be exposed to significant amounts of lead, especially in the first cup of water after the faucet has not been used overnight. Taking the faucet out of service is not helpful since running the water is necessary to clear the lead. The only practical option to avoid lead is to routinely flush the faucet for a few seconds before every use to clear the accumulated lead. This practice is clearly problematic for those in areas with water shortages. Additionally, many may not be aware of the need to flush a new faucet, which presents the need for consumer education.

Why does leaching present a special challenge for schools and child care facilities? The standard creates a significant issue for schools and child care facilities responding to state and local requirements for lead testing designed to protect young children from the harmful effects of lead exposure. If high levels are found, the facilities must take steps to reduce exposure, often by replacing faucets. Cautious facility managers typically want to test a new faucet to ensure limits are met before letting children drink from it. Some states even require this testing. However, as a result of the lead added to the brass, the samples could be well over state or local action levels in the 250 mL samples collected consistent with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recommended protocols. This may create an alarming situation in which facilities find elevated lead levels after installing brand new faucets.

Update on revisions to NSF/ANSI 61

The Joint Committee is responsible for managing revisions to the NSF/ANSI 61 standard to ensure it protects consumers from the health effects of the chemicals in plumbing components such as piping and faucets. The Joint Committee has balanced representation of three interests: 1) user/consumer; 2) industry; and 3) public health and safety/regulatory. No single interest, including plumbing manufacturers, may dominate the committee’s membership.

In response to concerns raised that new faucets can fail state and local testing standards for schools and child care facilities, in November 2017, the Joint Committee established a task group[1] to investigate tightening the lead leaching standard in NSF/ANSI 61. NSF does not require task groups to have a balanced representation of interests.

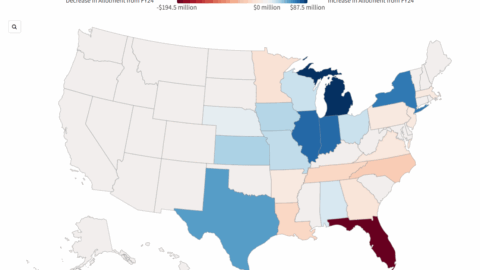

The task group learned from NSF staff that of 507 faucets it certified as NSF/ANSI 61 compliant, 73% of the faucets could meet a 1 µg limit – five times more protective than the current limit. For small valves and flexible plumbing connectors, a much higher percentage could meet the tighter limit. The labs that test other devices such as drinking water fountains, icemakers, and coffee makers did not provide the task group with any results. As a result of significant industry opposition, the task group reported to the Joint Committee that it could not reach a consensus recommendation on whether or not to tighten the standard.

In response, at its November 2018 meeting, the Joint Committee, by a vote of 24 to 2, established a new task group to consider proposals for optional certification approaches. While not mandatory, companies would have the option to obtain an additional certification under the NSF/ANSI 61 for those faucets and other devices that performed better than the current standard.

While a standard that covers all devices and is not optional sounds like an attractive approach, it would take several years to implement as all devices would need to be recertified. An optional certification approach, on the other hand, could be implemented more quickly since it supplements the existing certification program. In the short-term, the manufacturers only need to request the additional certification for the more rigorous standard, but it could later be required for all devices.

In the second task group, the proposal for an optional certification received support initially, including from EDF. But then, the task group members representing faucet and brass manufacturers voted against all proposed variations of an optional certification.

Despite the industry opposition, on May 13, 2019, the co-chairs of the second task group wrote a May 13, 2019 memo to the Joint Committee recommending that it vote in support of the optional certification. In the memo, the co-chairs said “that all of the arguments against a low lead annex were responded to and contradicted by technical arguments from those supporting the inclusion of optional requirements.” They noted that “the opposition presented no other values, no other test methods, and simply opposed the inclusion of any optional annex.” The memo included results of a straw ballot with an explanation of each person’s vote and the responses to each from the co-chairs.

Next steps and implications

The Joint Committee has not yet decided whether to proceed with a formal ballot in support of an optional certification. If it does, then it will seek public review and comment before proceeding. For more information on the process, see NSF’s policy.

Given the overwhelming support by the Joint Committee on the optional certification at its November 2018 meeting and that, unlike the task group, it is not dominated by industry representation, we are optimistic the committee will support moving forward.

If the Joint Committee declines to change the standard, then we anticipate that major retailers that sell brass faucets and other major buyers, such as school districts and builders, would use their leverage to specify higher standards.

EDF strongly supports an optional certification, which would empower consumers, schools, and child care facilities to be able to easily identify faucets that leach significantly less lead into drinking water so they can better protect children from unnecessary exposure to this toxic metal.

[Blog revised August 22, 2019 to remove sentence comparing new faucets to potential leaching from older faucets.]

[1] Tom Neltner served on both task groups.