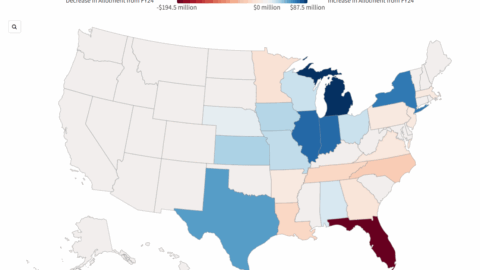

Over 7 million children exceed FDA’s new daily maximum intake level of lead

Tom Neltner, Senior Director, Safer Chemicals

This is the fourth in our Unleaded Juice blog series exploring how the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) sets limits for toxic elements like lead, arsenic, and cadmium in food and the implications for the agency’s Closer To Zero program.

In June, after issuing its proposed action levels for lead in juice, FDA tightened its Interim Reference Levels (IRLs) for lead to 2.2 µg/day for children and 8.8 µg/day for females of childbearing age—a drop of 27% from the original IRLs it established in 2018. We estimate this change increased the number of children over the IRL for lead from 1.2 million to more than 7 million.

The agency describes IRLs as daily maximum intake levels for lead in food and beverages. FDA scientists said the change was made to match the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) October 2021 revised blood lead reference value. This value is commonly known as the elevated blood lead level (EBLL).[1] FDA uses the “interim” label in recognition that there is no known safe level of exposure to lead and the neurotoxic harm it can cause. FDA anticipates matching the IRLs to future reductions in CDC’s reference value as the U.S. makes progress in reducing children’s exposure to lead.

We applaud FDA’s decision to tighten the IRLs. It is a good example of the type of continuous improvement to which FDA committed in its Closer to Zero Action Plan, which aims to lower levels of lead, cadmium, mercury, and inorganic arsenic in food that babies and young children eat and drink.

The challenge now is to translate the tighter daily maximum intake level into action levels for specific foods. Next steps for FDA should include:

- Further tightening its recently proposed action level for lead in juice.

- Using the revised lead IRLs as:

- The basis for its proposal for foods commonly consumed by babies and young children – currently stuck in the review process at the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB).

- A model for FDA’s anticipated IRLs for inorganic arsenic and cadmium under its Closer to Zero program.

What is FDA saying about the health risks from lead in food?

In tightening the IRL, FDA scientists reaffirm “a threshold has not been identified for lead’s effects on cognition, particularly IQ.” They acknowledge that “although the predicted IQ decrements associated with dietary lead exposure in the United States may seem minimal at an individual level, on a population level they are important.” They go on to say that “despite the smaller contribution of dietary lead to [blood lead levels] compared to other sources, no safe level of lead exposure has been identified for lead-induced neurodevelopmental effects, and therefore, reducing lead exposure from food is still relevant to public health.”

For that reason, FDA’s approach to the IRL is similar to CDC’s, which aims to drive blood lead levels closer to zero. CDC’s approach uses the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) to calculate the range of blood lead levels among U.S. children ages 1-5 years and then sets the EBLL at the 97.5th percentile. Children with blood lead levels at or above the EBLL represent approximately 500,000 children. Those levels can rise or fall based on a number of factors, including diet and community exposure.

CDC uses the reference value to identify children with the highest levels of lead in their blood compared with levels in most children in that age range in order to:

- Focus resources on children.

- Identify and eliminate sources of lead exposure.

- Take more prompt actions to reduce the harmful effects of lead.

CDC reviews and resets the EBLL every four years. FDA indicated it will adjust the IRL to ensure the dietary contribution to children’s blood lead levels stays below 10% of CDC’s EBLL.

New IRL should prompt FDA to further tighten its recently proposed limits for lead in juice.

In April 2022, FDA proposed action levels of 10 ppb in apple juice and 20 ppb for other juices. The agency’s supporting documentation for the proposal explained that the action levels will reduce the exposure of the 90th percentile of young children, from 1.57 µg/day to 1.07 µg/day – a 32% reduction.

The reduction, while significant, would mean that for the 90th percentile of young children, juices would represent almost half of children’s new IRL of 2.2 µg/day.

We are concerned that this major contribution from fruit juices will make it tougher for FDA to set other action levels for young children’s food and still stay under the new IRL for lead. While whole fruits have significant nutritional value, juices are less nutritious because much of the fiber and protein are removed. In addition, juices are high in calories and often very sweet, one of the reasons children like them. For these reasons, the American Academy of Pediatrics discourages serving fruit juices to young children.

In light of these factors, we think FDA can and should set tighter limits for lead in juice.

New IRL should serve as the basis for FDA’s proposal for young children’s foods.

In 2019, FDA evaluated data for foods collected from 2014-16 through its Total Diet Study (TDS) program to estimate young children’s dietary lead exposure. The study found that:

- Mean exposure ranged from 1.8 to 2.0 µg/day.

- 90th percentile ranged from 2.9 to 3.1 µg/day.

We estimate that exceed the new, tighter IRL.

In its Closer to Zero Action Plan, FDA committed to issuing action levels for lead in foods that young children typically eat and drink. Implicitly, the goal was to reduce the 90th percentile of consumption to less than the IRL. Limiting exposure to 2.2 µg/day would require that 90th percentile of young children’s intake be reduced by about 0.8 µg/day (from 3.0 to 2.2 µg/day). With the reduction in the contribution from juices of 0.5 ug/day, the other children’s food would need to be reduced by at least 0.3 ug/day.

Unfortunately, we do not know how FDA is planning to accomplish this reduction. It committed to releasing proposed action levels for children’s foods in April 2022. The agency sent the proposal to OMB on April 14, where it remains unreviewed after 4 months – past the 90 day review period.

New IRL should be a model for anticipated IRLs for other neurotoxicants.

In the Closer to Zero Action Plan, FDA committed to developing IRLs for inorganic arsenic, cadmium, and mercury. However, the agency has not indicated whether it will approach those IRLs in the same manner as it did lead. We think CDC’s approach of basing the level on the 97.5th percentile has merit, since these toxic elements also have no safe threshold of exposure.

Summary

FDA has taken an important step by lowering the IRL for lead. It needs to use this IRL more strategically in establishing action levels for lead in juice and for other children’s foods. It should also use the 97.5th percentile of exposure in establishing IRLs for other toxic elements addressed in Closer to Zero.

Sept. 9. 2022 Correction: Clarified that CDC uses the term Blood Lead Reference Value. It no longer uses the term EBLL.

March 23, 2023 Correction: Corrected estimated number of children over the old IRL of 3 micrograms per day from 2.2 to 1.2.

[1] To avoid confusion on acronyms and because it is more common, we use EBLL. The Department of Housing and Urban Development’s rule defines the EBLL to be the CDC’s Blood Lead Reference Value.

[2] FDA’s study did not provide sufficient statistical information to predict what percentile would be over 2.2 µg/day, but we calculated the following: Approximately 4 million children are born each year. Over a six-year period, that would mean ~24 million children in the age range, so 12 million children would be over the mean of 1.8 µ g/day. Assuming a typical distribution, we estimate that more than 7 million are over 2.2 µg/day.