By Tom Neltner, Senior Director, Safer Chemicals, Klara Matouskova, PhD, Consultant, and Maricel Maffini, PhD, Consultant

What Happened?

In our new study, we evaluated Generally Recognized As Safe (GRAS) notices—a total of 403 between 2015-2020—that food manufacturers voluntarily submitted to FDA for review. Our goal was to determine whether industry was adhering to FDA’s Guidance on Best Practices for Convening a GRAS Panel.

The guidance was designed to help companies comply with the law and avoid biases and conflicts of interest when determining whether substances added to food are safe and recognized as such by the scientific community. FDA published a draft of the guidance in 2017 and finalized it essentially unchanged in December 2022.

Our study found that no GRAS notices followed the draft guidance. Specifically, we also found there were high risks of bias and conflicts of interest because the companies:

- Had a role—either directly or through a hired third party—in

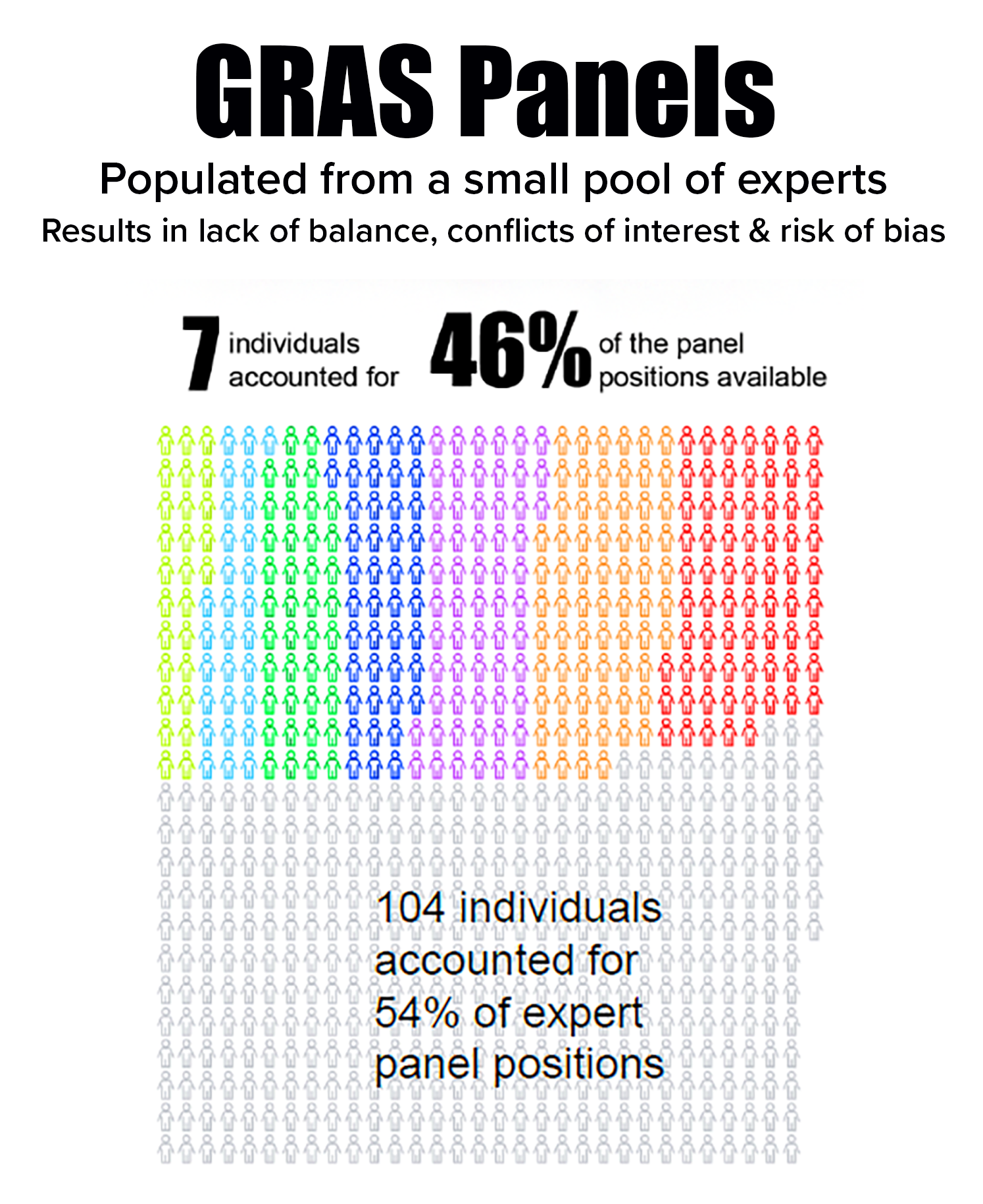

selecting panelists that likely resulted in bias and conflicts of interest. - Depended on a small pool of experts in which seven individuals occupied 46% of panel positions. The seven often served together, further enhancing risk of bias.

- Relied on panels that did not realistically reflect the diverse scientific community that evaluates chemical risks to public health—which is needed to comply with the law’s requirement that there be a “general recognition” within that community that a substance is GRAS.

Why It Matters

Since 1997, when FDA started reviewing voluntary notifications, the safety of food has relied heavily on companies properly determining that their new chemicals are GRAS before the chemicals are added to food. Records show that between 1997 and August 31, 2023, FDA was asked to review just over 1,100 GRAS determinations.

Our current best estimate is that manufacturers have notified FDA of less than half of the chemicals they are marketing as GRAS, based on the estimated 1,000 that bypassed FDA review as of 2011 and reinforced by our 2022 evaluation.

FDA has been aware of the risks of industry’s GRAS self-certifications since at least 2010, when the Government Accountability Office (GAO), a congressional watchdog agency, published a scathing report on FDA’s GRAS program. GAO recommended that FDA develop strategies to 1) “minimize the potential for conflicts of interest,” and 2) “monitor the appropriateness of companies’ GRAS determinations.” FDA took seven years to respond to that request. Rather than develop strategies, it relied on nonbinding guidance documents without an accompanying plan to ensure—or even monitor—compliance.

This study is the first to evaluate whether companies were adhering to FDA’s draft 2017 guidance when they voluntarily submitted GRAS notices for agency review. There have been five previous evaluations of GRAS notices,1 including one in 2013, which concluded that “between 1997 and 2012, financial conflicts of interest were ubiquitous in determinations that an additive to food was GRAS,” but there was no federal guidance at that time for comparison.

For GRAS determinations where the company chose not to notify FDA, we have not found any study evaluating whether those determinations followed the law or FDA’s guidance.2

It is hard to identify the public health consequences of secrecy, but occasionally we get a glimpse. That was the case in 2022 with tara flour, an ingredient linked to 329 illnesses and 113 hospitalizations in 36 states—or in 2010, with caffeine was added to alcoholic drinks, which caused what is known as the “wide awake drunk effect” in young people. In both cases, FDA had not been notified before the additives caused harm.

Our Take

We remain greatly concerned that decisions about what is safe for Americans to eat are being made by individuals with strong financial interests in the sale of their ingredients/additives. This risk of bias and these conflicts of interest are particularly a problem when there is a small cadre of individuals who have made GRAS panel participation a source of income for more than two decades.

This study adds to the mountain of evidence that FDA’s GRAS program is broken. The agency’s lack of systematic post-market oversight continues to create health risks, as companies determine new chemicals are safe while keeping the agency in the dark. We are not alone in our concerns; last session both the House and the Senate considered legislation to fix the system. In addition, consumers continue to rate food chemicals as their top food safety concern.

The agency’s well-intentioned guidance on convening GRAS panels is only a half-step to limit bias. It fails to address in any serious way the conflicts of interest that occur when companies rely on their employees or hired consultants for GRAS determinations. It may even backfire and push companies to bypass GRAS panels altogether and rely solely on employees and consultants to decide whether new chemicals added to food are safe.

The GRAS Decision Tree

It is important to note three things about the FDA’s GRAS program:

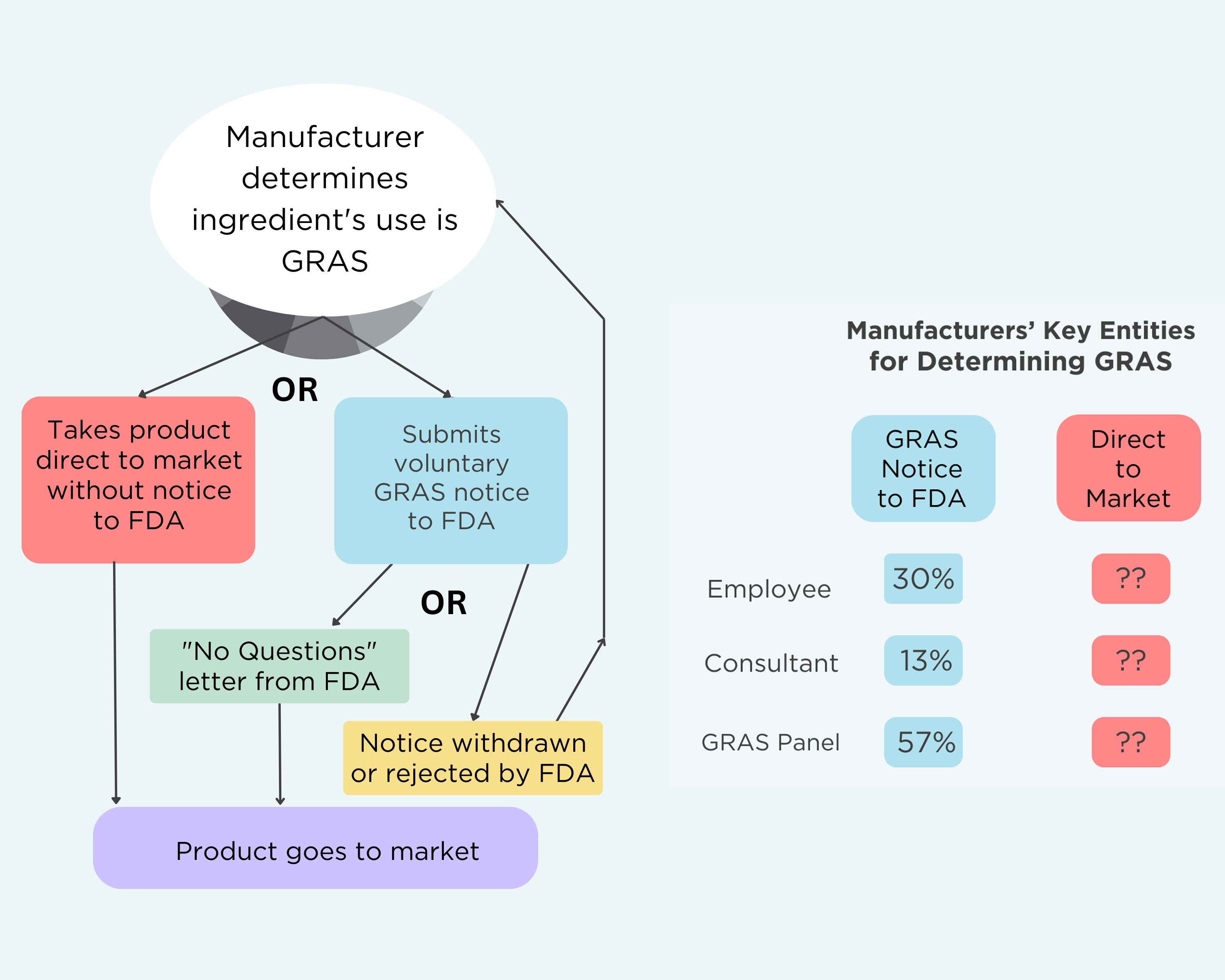

- Manufacturers have no legal obligation to submit GRAS notices to FDA. They make GRAS determinations regardless of whether they ever alert FDA about a specific chemical. If they determine that their ingredient is GRAS, they are allowed to rely on reviews by their own employees or a hired consultant if they wish.

- Manufacturers are legally allowed to take their product straight to market. They do not have to inform FDA or go through any other review process.

- FDA reviews the GRAS notices and publishes an opinion. There are three possible outcomes from FDA review: 1) FDA can issue a “No Questions” letter when it agrees with the GRAS determination; 2) the agency rejects the notice; or 3) the manufacturer withdraws the notice. A withdrawn GRAS determination can be resubmitted.

Here’s what the GRAS decision tree looks like—and who plays a role in those decisions:

Next Steps

We will continue to press FDA to fix the broken GRAS program by requiring notice and providing necessary oversight to ensure compliance with the law. As part of this effort, we will:

- Highlight specific examples of chemicals that do not appear to be properly designated as GRAS or safe.

- Assess whether FDA is issuing “No Question” letters for GRAS notices that do not conform to the guidance.

- Evaluate whether FDA is taking action on withdrawn or rejected notices, including reviewing the agency’s database of substances whose use is not GRAS and its warning letters.

- Encourage Congress and the media to investigate GRAS issues to understand the public health implications.

Download a PDF copy of this blog post

NOTES

1 FDA in 2010, Neltner et al. in 2013, Center for Public Integrity in 2015, FDA in 2016, and Hanlon et al. in 2017.

2 We expect that the companies are taking extra care with notices submitted to FDA because the agency is reviewing.