An environmental justice case study: how lead pipe replacement programs favor wealthier residents

Tom Neltner, Chemicals Policy Director and Lindsay McCormick, Program Manager

Dr. Karen Baehler and her team at American University’s Center for Environmental Policy, with support from EDF, recently published a peer-reviewed case study highlighting the environmental justice issues that arise when water utilities require property owners to pay when they replace lead service lines (LSLs) that connect homes to the water main under the street. Our experience indicates that the vast majority of the 11,000+ water utilities in the U.S. engage in this practice. Based on the findings, these utilities need to reconsider their programs as they address the more than 9 million LSLs nationwide.

The study found that Washington, DC residents in low-income neighborhoods between 2009-2018 were significantly less likely than those in wealthier neighborhoods to pay for a full LSL replacement and, therefore, had an increased risk of harm from lead exposure from a partial LSL replacement.

The practice of requiring customers to pay for a full LSL replacement also raises civil rights concerns in cities like Washington, DC that have a history of racial segregation, redlining, and underinvestment in neighborhoods predominately comprised of people of color. If a utility that follows this practice also receives federal funding such as state revolving loan funds (SRFs), it may be violating Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. While Washington, DC largely resolved the issue in 2019 by banning partial replacements and addressing “past partials” left in the ground, this scenario is replicated across the country.

The problem of partial LSL replacements

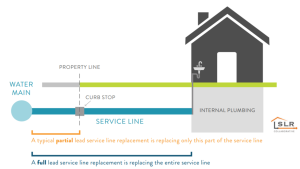

The figure below shows the difference between a full and partial LSL replacement.

To maintain their infrastructure, utilities regularly replace aging drinking water mains. The issues arise when the water mains are attached to LSLs because the work disturbs these lead pipes.

A full LSL replacement provides significant long-term reductions in the risk of lead exposure in a customer’s drinking water. However, a partial LSL replacement – that leaves in place the lead pipes on private property – creates short-term spikes in lead levels that are much higher and last longer and does not reliably reduce the risk of lead exposure over the long-term.

In 2011, EPA’s Science Advisory Board found that in “water distribution systems optimized for corrosion control, full [LSL replacements] ha[ve] been shown to be a generally effective method in achieving long-term reductions in drinking water [lead] levels.” The Science Advisory Board also stated that “[partial LSL replacements] have not been shown to be reliably effective in reducing drinking water [lead] levels.”

Customers thus face a stark choice: accept the risk of increased lead exposure from a partial replacement or pay potentially thousands of dollars to ensure the LSL is fully replaced.

Where customers are unable or unwilling to pay, utilities typically proceed with a partial LSL replacement, upgrading the portion of pipe that runs from the water main to the curb stop (usually near the property line), and leaving in place the lead pipe that connects the curb stop to the home.

In essence, partial LSL replacements not only increase the risk of lead contamination in the home’s drinking water, threatening children’s brain development and putting adults at higher risk of heart disease and other harm, they also leave the work half-done to be finished in the future at a greater overall cost.

Environmental justice issues when utilities force customers to choose

The study from Dr. Baehler and her team shows how the practice of partial replacements can result in a major equity issue, with significant health implications for lower-income households.

Using Washington, DC as a case study, researchers evaluated data on more than 3,400 full and partial LSL replacements conducted in the nation’s capital from 2009 – 2018. During this ten-year period, the local water utility, DC Water, followed the common cost-sharing practice for replacing LSLs. The utility covered the cost of replacing LSLs located on public property but required customers to pay to replace LSLs on private property. The utility took measures to reduce the cost, but customers still needed to pay a contractor an average of $2,000, with prices ranging from $1,000 to $10,000.

According to the study, a neighborhood’s household income was a major predictor of the prevalence of full LSL replacement. Residents in higher income neighborhoods in the city had a significantly greater probability of paying for full replacement of their LSL, with customers in lower income neighborhoods more likely to have a partial LSL and the greater risks of lead exposure that come with it.

Importantly, the study suggests that these patterns of inequity “have policy and program relevance far beyond one city’s boundaries.” The same environmental justice issues can arise across the country because many other water systems employ the same key features as those used by DC Water during the period studied.

Some have already stopped partial LSL replacements

In late 2019, Washington, DC approved an ordinance stopping partial LSLs replacements and providing financial support for homeowners who had partial replacements in the past.

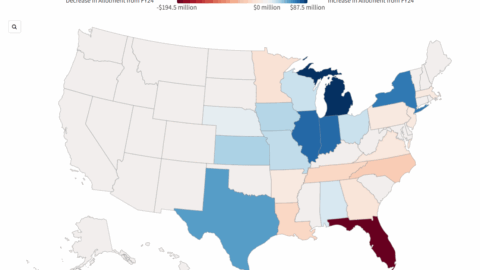

Other cities like Cincinnati, Milwaukee, and Philadelphia have also rejected the practice of partial LSL replacements, and states like Illinois, Michigan, and New Jersey have recognized the risks from partial LSL replacements and banned the practice.

A new influx of federal funds from the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act enacted in November 2021 should also benefit efforts to stop partial LSL replacements. The money goes to SRFs and includes $15 billion specifically for LSL replacement programs. The challenge ahead is to ensure the funds are spent right to the benefit of all residents.

The study’s conclusions seem like common sense, but having them documented in a statistically representative manner in a peer-reviewed journal makes them more useful to policy makers. In light of the evidence, utilities demanding that low-income residents pay to replace LSLs on private property should seriously consider the environmental justice and civil rights implications. States administering SRFs should as well. As EPA reminds us in its December 17 Federal Register notice on the Lead and Copper Rule, “States and water systems receiving federal funds have an affirmative obligation to implement effective nondiscrimination compliance programs.”

It is time utilities and states took this obligation seriously.