New Study Highlights Lead in Water at Child Care Facilities and Holes in Current EPA Rule

Lindsay McCormick, Program Manager

This month, EDF published an article along with collaborators from Auburn University and Mississippi State University, based on a pilot we conducted in partnership with local organizations[1] to comprehensively test and remediate lead in water at 11 child care facilities in Illinois, Michigan, Mississippi and Ohio.

The study found that while over 75% of first draw samples contained lead levels under the 1 ppb level recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 10 of 11 child care facilities produced at least one sample above that level. We fixed problems at the facilities, including replacing 26 contaminated fixtures and two lead service lines.

One of our goals with the pilot was to increase awareness of the issue of lead in water at child care facilities, given that children under the age of six are most vulnerable to harm from lead due to their developing brains and, further, formula-fed infants who rely on drinking water to reconstitute formula are among the most exposed. Lead service lines – the largest source of lead in water – are also more likely to be found at child care facilities than schools because schools generally have larger water service lines that are rarely made of lead.

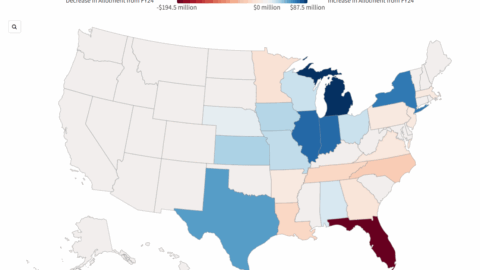

Since we began the pilot in 2017 the number of states requiring child care facilities to test for lead in water has increased from four to 11. Lead service line replacement at child care facilities is also becoming more commonplace. For example, Greater Cincinnati Water Works initiated a program to provide no-cost replacements to all licensed child care facilities and Denver Water’s program is prioritizing “critical customers.”

EPA also finalized a revised Lead and Copper Rule,[2] that includes, for the first time ever, a national mandate for water utilities to test lead in water at child care facilities. Unfortunately, the approach is significantly limited, as we blogged about before, requiring testing only at two outlets per facility – which could miss lead problems entirely. It also fails to require discovered problems to be fixed where lead is found at any level.

As part of the study, we wanted to dig into the implications of EPA’s approach, so we calculated the probability of detecting lead at two random first draw samples at study child care facilities under the rule’s sampling scheme and compared this at different hypothetical action levels. We found that, when applied to our 11 study sites, the sampling scheme would be unlikely to prompt fixes. For example, when assuming even a conservative action level of 1 ppb, the probability of randomly selecting two outlets that would trigger remediation was below 50% at all but two facilities – despite the fact that almost every study site had at least one outlet with greater levels.[3] Our results underscore the limitations of the sampling at just two outlets given the localized and unpredictable nature of lead contamination at fixtures.

Today, the Biden Administration is reconsidering the final Lead and Copper Rule promulgated under the Trump Administration. We expect that the agency will publicize its plan for moving forward by December. We are hopeful that EPA will improve the child care testing provisions of the rule to better protect children from lead exposure.

[1] Local partners recruited child care facilities into the study and oversaw sample collection at each site: Elevate (Chicago), Greater Cincinnati Water Works (Cincinnati), Healthy Homes Coalition of West Michigan (Grand Rapids), Mississippi State University Extension (Starkville and Tunica), and People Working Cooperatively (Cincinnati).

[2] The rule will not go into effect until December 16, 2021, and utilities have until September 16, 2024 to come into compliance.

[3] Note that sampling was conducted after lead service line replacement in this study.