Promising proposal for addressing lead in schools and licensed child care – but gaps remain

Lindsay McCormick, Program Manager, and Tom Neltner, J.D., Chemicals Policy Director

See all blogs in our LCR series.

Update: On February 5, 2020, we submitted comments to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) on its proposal.

Through its proposed revisions to the Lead and Copper Rule (LCR) under the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA), EPA made the unprecedented move of proposing to require community water systems (CWSs) to test for lead in water at all schools and licensed child care facilities constructed prior to 2014. The current rule only requires testing if the facility is itself a regulated water system (e.g., uses own private well). While EDF fully supports testing in these facilities, we are concerned that EPA has overlooked several major issues, especially in the child care context.

Based on our experience – including a pilot project to test and remediate lead in 11 child care facilities, a training program for child care providers in Illinois, and monitoring of state child care testing requirements across the country – we believe that addressing lead in child care facilities is an important opportunity to improve public health. Though schools are also critical, we’ve focused on child care facilities as they present a major gap due to a number of reasons. First, children under the age of six are more susceptible to the harmful effects of lead – and those at the highest risk are infants who are fed formula reconstituted with tap water. Second, child care, especially home-based facilities, are often smaller operations than schools, and therefore more likely to have a lead service line. Finally, child care facilities often lack robust facility support and public accountability that schools may have.

From our background on this issue, we have identified three key flaws with EPA’s proposal. Specifically, it:

- Ignores lead service lines,

- Relies on inadequate sampling, and

- Does not provide sufficient support for remediation.

We also are concerned that the result of this proposed rule may sound like “one hand clapping.” If state licensing agencies and local health departments are not requiring or promoting testing, child care facilities are unlikely to cooperate, making it more difficult for CWSs to comply with the requirement. For this requirement to have greatest effect, CWSs need the support and participation of all parties involved.

This blog will provide an overview of EPA’s proposed requirement and an analysis of each of the key issues.

Details on EPA’s proposed testing requirement

Under the proposal, CWSs would be legally responsible for ensuring that all schools and licensed child care facilities they serve have their water tested every five years (20% a year on a five-year cycle) – unless the system can document that the facility operators refused entry or declined to participate. The rule would also require CWSs to share the sampling results with the respective facility, as well as the local or state health department. CWSs in states or localities that already have an equivalent or more stringent school or child care testing requirement would be able to receive a full or partial waiver. It should be noted that unlicensed child care facilities are not covered by the rule.[1]

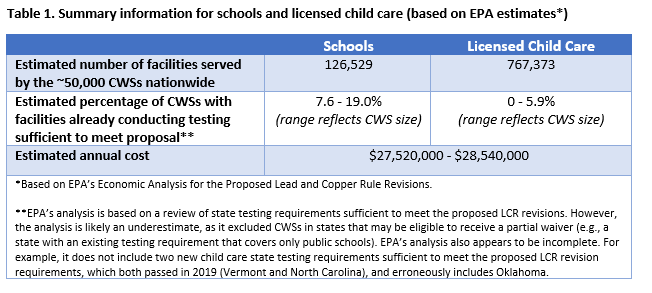

EPA justified the proposed requirement because it “sees a need to assist schools and child care facilities” and that “[w]ater systems are best positioned to provide this assistance as they have developed the technical capacity to do this work in operating their system and complying with drinking water standards.”[2] The agency also provided an Economic Analysis, which we summarize in Table 1 below.

EPA also considered an “upon request” option, where CWSs would only be required to provide assistance upon request from a school or licensed child care. Under this option, the CWS would contact each facility annually to determine its interest in the program. Compared to the mandatory option, with an estimated cost of about $28 million, the “upon request” approach would cost just over $10 million. The agency assumed that only 5% of facilities would request assistance each year.

EPA ultimately rejected the “upon request” option, positing that more facilities would participate in a mandatory program. It is also worth noting that an “upon request” option could present serious equity concerns – where wealthier schools and child care facilities make a disproportionate amount of such requests and therefore benefit more from the CWS’s assistance. Further, while an “upon request” program may be relatively effective for schools with public accountability, child care facilities are typically private institutions with less pressure to cooperate with water utilities and demonstrated hesitancy to participate in voluntary programs.

Areas for improvement

EPA should prioritize lead service lines at child care facilities

When lead service lines (LSLs) – lead pipes connecting the main under the street to the building – are present, they are the largest contributor of lead in water. While not typically found at larger buildings, home-based child care operations (as well as small school annexes) may have LSLs.

Though the proposed rule would require water systems to conduct an inventory of LSLs and notify all property owners (including schools and child care operations) of their presence on an annual basis,[3] it does not highlight or prioritize these facilities for LSL replacement. The proposal also requires CWSs to develop a list of all schools and licensed child care facilities it serves as a starting point for conducting testing; however, the proposal treats this list as distinct from the LSL inventory.

In addition, based on our pilot in child care facilities, EDF recommends that LSLs be identified and removed first, followed by sampling at each drinking water tap to identify lead sources internal to the building. Without first replacing the LSL, the first draw testing results will not provide useful information to pinpoint whether the lead is coming from the LSL or a fixture. This calls into question EPA’s proposed sampling approach which ignores the presence of an LSL.

EPA could address these issues by requiring CWSs to cross reference the LSL inventory and schools/child care list to both prioritize LSL replacements in such locations and inform the testing schedule to ensure testing occurs after LSL replacement where possible. Ideally the appropriate state agency would make public a list of all schools and licensed child care facilities with LSLs; however, EPA does not have the authority under the SDWA to require this.

EPA’s sampling scheme is inadequate and not supported by the evidence

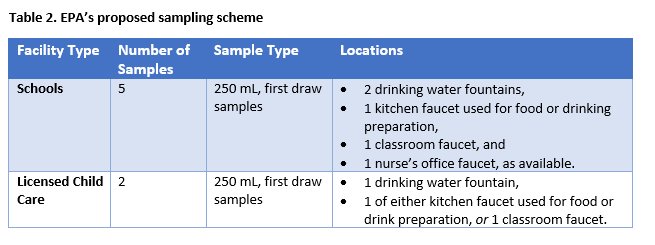

EPA has proposed an extremely limited sampling scheme. Instead of requiring all drinking water outlets to be tested, only five taps at schools and two taps at licensed child cares would need to be sampled under the proposal (section 141.92 (b)(1)).

EPA’s proposal runs contrary to its own voluntary guidance, 3Ts for Reducing Lead in Drinking Water Toolkit, that recommends that all outlets possibly used for water consumption be tested, including any “sink known to be or visibly used for consumption (e.g., coffeemaker or cups are nearby),” as well as a follow-up 30 second flush sample if the first draw sample is elevated.[4] It is also inconsistent with many state testing requirements, which commonly mandate sampling at every drinking water outlet.

Because lead contamination in fixtures is typically localized and unpredictable, such a limited sampling scheme may create a false sense of security for facilities that receive negative results. For example, in our pilot project, we found that while the majority of water samples had non-detectible levels of lead, seven of the 11 child care facilities had at least one drinking water sample above EDF’s benchmark for action – resulting in a total of 17 fixture replacements.[5] On average, we tested 18 drinking water fixtures at each facility, with a range of six to 59.[6] If we had chosen only two fixtures, it is unlikely we would have located and removed the lead sources.

EPA’s Economic Analysis provides no rationale for the agency’s decision to use such a limited sampling scheme. Presumably the agency’s decision was made to limit cost. However, much of the effort and cost associated with sampling for the CWSs revolves around getting into the facility in the first place. EPA estimates CWSs will spend 144.8 minutes (2.4 hours) per facility – identifying the facilities, coordinating sampling schedule and logistics, traveling to the facility, conducting facility walk-throughs, etc. – before sampling begins. After such an effort, it makes little sense to conduct such limited, arbitrary sampling. In contrast, EPA estimates 10 minutes to collect a sample and $21.58 for analysis by a commercial lab. (See Table 1A for additional detail.)

EPA ignores the elephant in the room – fixing problems once identified

EPA’s proposal would place the burden of fixing high levels of lead on the schools and child care facilities. CWSs would only be required to provide facilities with the testing results along with EPA’s 3Ts toolkit.

While the 3Ts toolkit is a helpful resource – with instructions for more detailed sampling, remediation options, and templates for communication with parents – ultimately facility staff will be fully responsible for determining when there is a problem and then identifying and financing appropriate solutions. From our experience, child care facilities need significant support to understand testing results and remediation options. CWSs have critical contextual information (such as local water quality or cost of remediation options like flushing or LSL replacement), that could help facilities respond to testing results in a thoughtful manner and avoid wasteful efforts. EPA failed to carefully consider what types of technical assistance the CWS may be able to offer. Further, schools and child care facilities would not be required to remediate based on sampling, as EPA does not have the authority under SDWA to regulate these entities.

In addition, relying on the facilities to take appropriate action will be particularly challenging given that the proposed rule does not establish an action level based on such testing. When EPA updated its 3Ts toolkit in October 2018, the agency removed the action level of 20 parts per billion (ppb) in the previous version, recognizing that there is no safe level of lead. The guidance states, “[i]f testing results show elevated levels of lead in drinking water, then you should implement remediation measures,” but EPA does not define “elevated lead level” anywhere in the toolkit. While arguably appropriate for a guidance document, it is inappropriate for an agency rule not to set a level to trigger action. This will place the burden on schools and child care staff to identify an appropriate action level for themselves – a particular challenge for understaffed and under resourced child care operations. Today, state and local testing requirements rely on action levels ranging from 1-20 ppb.

The rule also falls short of requiring the CWSs to take advantage of the information gleaned from the schools and child care testing as it plans LSL replacement or optimizes corrosion control. At a minimum, this testing data should be integrated in the CWS’s system-wide data for making decisions on corrosion control.

One hand clapping

In an effort to fill a regulatory gap, EPA proposed requiring CWSs to ensure water is tested for lead at all schools and licensed child care facilities through its LCR revisions. While an important objective, water testing at these facilities will be a challenge without the support and participation of a wide variety of actors – including the state and local education and licensing authorities, health departments, and the schools and child cares themselves.

Where these critical partners are absent, the result may be like the sound of one hand clapping. This may well happen in many states because, under SDWA, EPA only has the authority to regulate water utilities – not schools, child care facilities, or any of the other essential players. We encourage other federal agencies and national organizations to consider how to support EPA’s objective, such as through updating national child care recommended guidelines (e.g., Caring for Our Children Basics, NRC Caring for Our Children national standards).

[1] According to a 2018 National Women’s Law Center report, approximately 24% of children are cared for in unlicensed home-based child care with a relative.

[2] Economic Analysis for the Proposed Lead and Copper Rule, p 3-53. https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OW-2017-0300-0003.

[3] See sections 141.84 and 141.85

[4] See p. 31 of EPA’s 3Ts toolkit.

[5] We replaced 26 fixtures in total, but 9 of these replacements were bathroom sinks that may not be used for drinking.

[6] This number excludes tested fixtures in bathrooms, storage/laundry rooms, and outside hose bibs.