Richard Denison, Ph.D., is a Lead Senior Scientist.

[My colleague Ryan O’Connell assisted in the research described in this post.]

[Use this link to see all of our posts on Dourson.]

In a series of earlier posts to this blog, we have described and documented numerous conflicts of interests that Michael Dourson, the Trump Administration’s nominee to head EPA’s toxics office, would bring to the job if he is confirmed.

(A vote on his nomination by the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee is currently scheduled for this Wednesday at 10am EDT. If he is voted out of committee, a majority vote of the full Senate would then be required for his nomination to be confirmed.)

Dourson has worked on dozens of toxic chemicals under payment from dozens of companies. Two consistent patterns emerge when his reviews are examined: The process he typically uses to conduct his reviews is riddled with conflicts of interest. And his reviews typically result in him recommending “safe” levels for the chemicals that are weaker, often much weaker, than the established standards in place at the time of his reviews.

If confirmed, Dourson would oversee most of the chemicals and companies he has worked on and with. The chemicals include numerous pesticides coming up for review shortly under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), as well as three chemicals that are among the first 10 EPA is now considering under the recently amended Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA).

To further gauge the impact Dourson could have if confirmed, we have looked a bit farther down the road. TSCA requires EPA to be conducting risk evaluations on at least 20 chemicals by December 2019. At least half of those chemicals are to be drawn from EPA’s so-called Work Plan for Chemical Assessments.

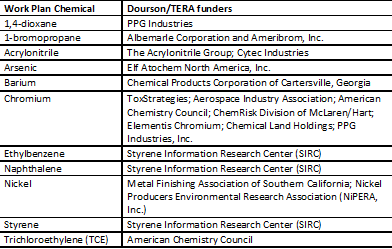

Using information available on the website of Dourson’s company, Toxicology Excellence for Risk Assessment (TERA), as well as his published papers, we compared the list of chemicals he/TERA have worked on to those on the EPA Work Plan. We found that 22 chemicals overlap. We then examined each chemical Dourson or TERA worked on to determine whether Dourson or TERA was paid for their work by their manufacturers or industrial users of those chemicals.

For at least half – 11 of the 22 Work Plan chemicals – we identified such funding. These include the three chemicals noted earlier that are among the first 10 EPA is currently evaluating: 1,4-dioxane, 1-bromopropane, and trichloroethylene. These and the eight additional Work Plan chemicals we identified are listed in the accompanying table, along with the corporate interests that hired Dourson or TERA to work on them.

This analysis only deepens the basis for concern over Dourson’s nomination: If confirmed, he would have full authority over the selection of which Work Plan chemicals EPA selects next for risk evaluations, not to mention the scope and content of those evaluations. Many other aspects of TSCA implementation would fall entirely under his purview as well, including those that are central issues in current litigation over EPA’s prioritization and risk evaluation rules:

- what uses are included in and excluded from risk evaluations;

- whether risk determinations are made for specific uses rather than across uses of a chemical;

- which and how many chemicals are designated low vs. high priority;

- how many and which company-requested risk evaluations EPA grants, and the scope of those evaluations; and

- whether and when to use the expanded testing authority the new law gave EPA.

The stakes are indeed high. Public health protection demands that the Senate reject Dourson’s nomination.