From California to Idaho: Protecting rural pit stops on the monarch butterfly’s great migration

As a kid growing up in northern California, I found myself migrating to the beaches and boardwalk of Santa Cruz (along with tens of thousands of other land-locked youth) to escape the sweltering inland heat each summer.

Now, as an adult more than a decade into my conservation career, I’ve come to learn that the monarch butterfly, one of America’s most well-known and beloved insects, is drawn to the same place, only during winter.

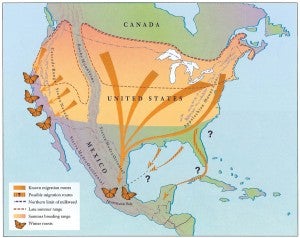

The western population of monarch butterflies spends their winters along the California coast, seeking the temperate climate and coastal forests the area offers. This overwintering habitat extends as far North as the San Francisco Bay Area and as far South as San Diego along the U.S.-Mexico border. But the highest concentrations occur in a handful of sites in and around Santa Cruz.

A few weeks ago, I paid a visit to my old summer stomping grounds to see this iconic North American butterfly.

First stop: Natural Bridges State Park

I wanted to catch a glimpse of the monarchs while they were in Santa Cruz this December, before they dispersed across the West – their flight paths dedicated to sustaining the next generations of their kind.

My first stop was at Natural Bridges State Park, where, quickly upon entering the park, I discovered a half dozen orange clusters of monarchs clinging tightly to branches in a protected eucalyptus grove. Scientists estimated that as many as 8,000 monarch visited this site at the peak just before Thanksgiving.

The weather was a chilly 50 degrees, a temperature too cold to allow the insects to take flight. Monarch butterflies are most active when temperatures exceed 60 degrees. They don’t fly at all when temps fall below 55 degrees.

While at the park, I met and chatted with Ron, an amiable retired biology teacher who serves as a volunteer docent at the park. He was concerned that a family of Steller’s jays had taken residence in the grove. These Steller’s jays were known to fly directly into the assembled butterflies in an attempt to scatter them from their protected clusters, occasionally feeding on the monarchs.

Ron pointed me toward an even bigger population of monarchs at a site a mile down the road near Lighthouse Point – a stone’s throw from the Santa Cruz surfer statue.

Temperatures had warmed a bit by the time I arrived at the spot, and the sun shone brightly on the face of a tall Monterey cypress tree covered with thousands of monarchs. The sun’s rays offered enough warmth to allow me to witness a few hundred butterflies take flight, flitting about aimlessly (or at least that’s the way it looked to me). Nonetheless, it was a remarkable sight.

Next stop: milkweed

In the coming weeks, the monarchs I saw in Santa Cruz will set off from the coast, heading inland to mate and in search of milkweed plants on which female monarchs will lay eggs.

Monarch butterflies only lay their eggs on milkweed and the larvae exclusively feed on the milkweed sap, which is toxic to most other organisms. Monarchs have a unique capacity to sequester the toxins in the sap, which in turn makes them unpalatable to many predators.

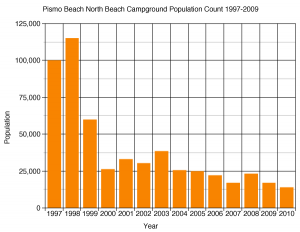

Unfortunately, milkweed is in decline across the U.S., accounting for a significant portion of the population decline. Habitat loss and increased use of pesticides are largely to blame for the loss of milkweed. Climate change poses an additional threat to the species’ habitat and population.

Efforts are underway by organizations like the Xerces Society, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to develop appropriate seed sources and to plant milkweed throughout the range.

More milkweed, more monarchs

EDF recently decided to join in the effort to protect and restore habitat for the monarch butterfly, applying our own market-based approach to habitat protection – through habitat exchanges – to bring more of these conservation efforts to private lands, namely agricultural lands.

Since farmers, ranchers and forestland owners manage much of the habitat appropriate for milkweed, we are working to develop a tool that will accurately determine the value of habitat for monarch, which will in turn allow incentive payments to be directed to the right places at the right time, ensuring maximum bang for the buck, and for the butterfly.

If we are successful, I hope to see more monarchs returning to their old overwintering stomping grounds in Santa Cruz year after year.

Related:

Why we need a new way to protect wildlife >>

Habitat exchanges: How do they work >>

USDA invests $350 million to protect farmlands, grasslands and wetlands