The Grand Canyon Protection Act would advance water security and environmental justice at critical time

Climate change and drought are bringing home the urgent need to protect the Grand Canyon and secure clean water supplies for all communities in the Colorado River Basin. With the compounding threat of uranium mining, the stakes are high in the Grand Canyon — a global treasure, economic driver for Arizona, and place of great cultural and spiritual importance to at least 12 sovereign indigenous nations.

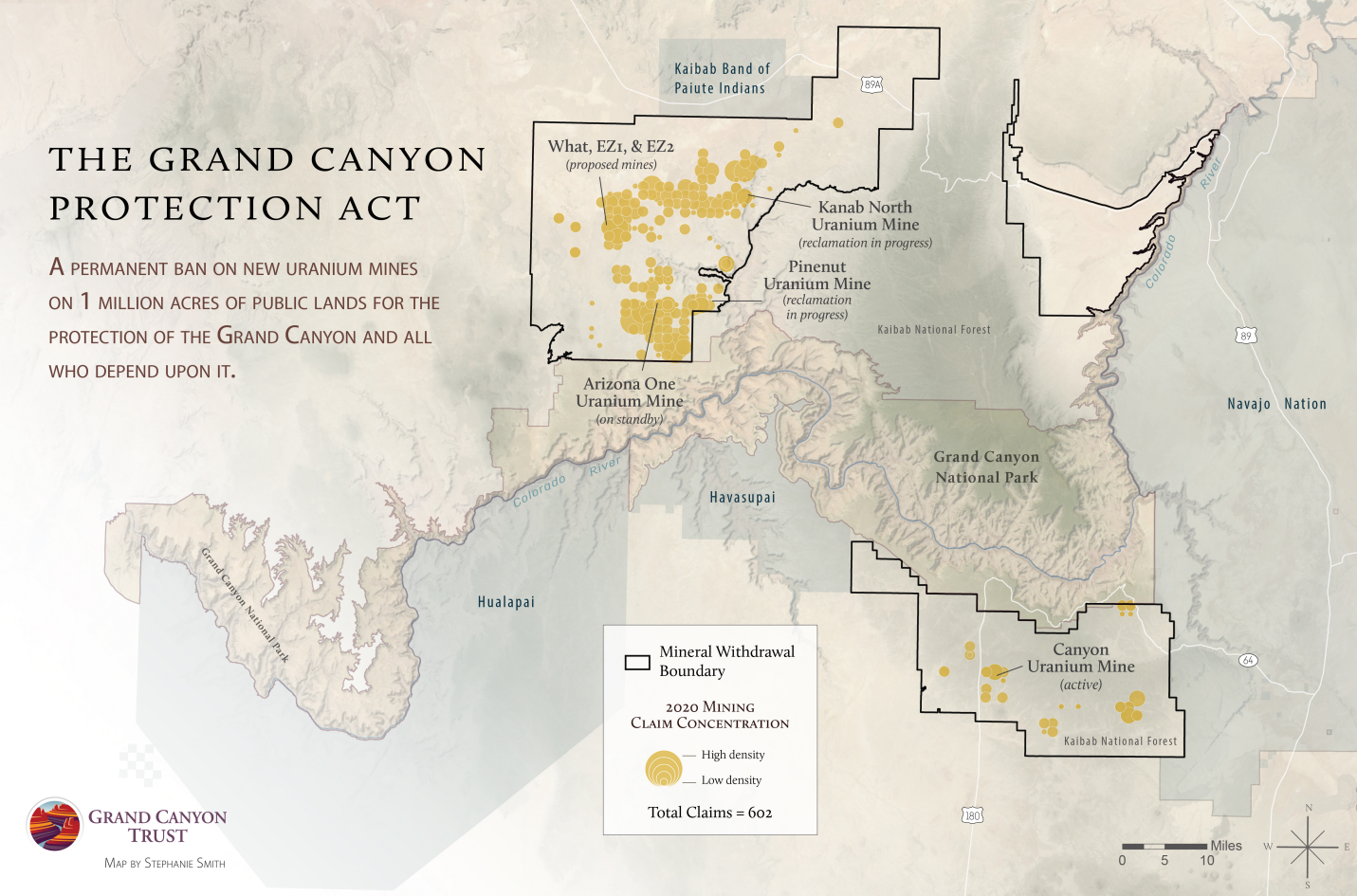

If passed, the Grand Canyon Protection Act would make permanent the 20-year temporary ban (enacted in 2012) on new uranium and other hard rock mining on about 1 million acres of public land around Grand Canyon National Park. The bill was introduced earlier this year by Reps. Raúl Grijalva and Tom O’Halleran and Sens. Kyrsten Sinema and Mark Kelly, all Arizona Democrats. It has passed out of the House but has not yet received a vote in the Senate.

Groundwater’s importance to the Grand Canyon

Although the Colorado River flows through the Grand Canyon, groundwater is the primary drinking water source for the region and its massive tourism economy — an economic engine that supports 13,000 rural jobs and over 6 million annual national park visitors, who directly spend about $1 billion in neighboring communities.

Additionally, the Grand Canyon’s complex groundwater systems feed springs and creeks, which in turn support the unique ecosystems, Havasupai Tribal homelands and magical oases found below the rim. At least 750 springs percolate and flow in the Grand Canyon, supporting species diversity up to 500 times greater than the surrounding landscape.

Today, uranium mining threatens these critical groundwater resources at a time when the Grand Canyon region cannot afford that risk.

Water security in the era of aridification

Although science has made important advancements, there is not yet a systematic understanding of how groundwater travels the Grand Canyon’s complex geologic layers and aquifers. Studies that have been conducted revealed groundwater behaving in surprising ways, finding water can travel over 20 miles, in some cases within only a few days.

Studies suggest that, at least in some places, contamination could spread quickly and far through the region’s aquifers. We simply do not understand enough to risk water security and the tribal homelands of the Grand Canyon region.

Moreover, climate change-driven aridification is causing already scarce water to become even scarcer. The Colorado River Basin lost a staggering 53 million acre-feet of water over a recent nine-year period, with groundwater depletion contributing to over three-quarters of that loss. In the Grand Canyon, as one example, flows in groundwater-dependent and popular Garden Creek have declined by 25%.

The Grand Canyon region holds less than 0.20% of the nation’s known uranium reserves. We cannot tolerate any risk of sacrificing its already scarce groundwater supplies for a negligible amount of uranium. Once groundwater that has taken hundreds or even thousands of years to accumulate is either depleted or lost to radioactive contamination, it’s gone, and there will be no additional water supplies.

A step forward on water justice

The Inter Tribal Association of Arizona, which includes 21 tribal nations, passed a resolution supporting the Grand Canyon Protection Act, calling the expansion of uranium mining the “greatest risk” to religious, cultural and traditional land use by Native peoples in the area.

Uranium mining has a toxic, exploitative legacy that has been well documented in such work as the book Yellow Dirt. A recent University of New Mexico study found 26% of Navajo women and some newborn infants still had concentrations of uranium in their body that exceeded levels found in the highest 5% of the U.S. population. The impacts, especially on tribal lands in the nearby Four Corners area, have been severe, affecting families, communities and landscapes across multiple generations.

Elevated levels of uranium still persist from long-idled mines in the Grand Canyon region. Meanwhile, the active Canyon Mine (renamed the Pinyon Plain Mine) has repeatedly flooded with groundwater after its mineshaft pierced the water table.

Though not yet even producing ore, the Canyon Mine experience offers a forewarning of the real and significant risks that “modern” uranium mining still poses for communities living in and around the Grand Canyon.

No one bears greater risk than the Havasupai Tribe, whose name translates to “The People of the Blue Green Waters.” The Tribe’s identity is interwoven with the waters of Havasu Creek, which also serves as their water and driver of their tourism economy. Havasu Creek is fed by a deep regional aquifer that lies beneath the Canyon Mine and other mining claims.

Passing the Grand Canyon Protection Act is essential

Passing the Grand Canyon Protection Act may not halt operations at the Canyon Mine. But it will permanently stop the hundreds of other mining claims waiting for the temporary ban to expire, taking a major step forward to help secure clean water supplies and environmental justice for the region.

With the Grand Canyon Protection Act, Congress has an opportunity to help safeguard a global treasure and its waters, protecting communities, livelihoods, and the many deep spiritual and cultural connections to this irreplaceable landscape for generations to come.

We are grateful to Sens. Sinema and Kelly and Reps. Grijalva and O’Halleran for their leadership on this issue. Now let’s get the Grand Canyon Protection Act across the finish line.