5 principles for resilient groundwater management in Texas

Although Texas has a solid foundation for managing groundwater, this foundation is cracking under the combined pressures of increasing demand and decreasing supply.

These pressures are pitting rural areas against urban areas and landowners against each other, with groundwater conservation districts caught in the middle.

To overcome these challenges and ensure resilient water supplies, Texas leaders must improve the state’s framework for managing groundwater. That means finding common ground among diverse stakeholders on how to best sustain supplies.

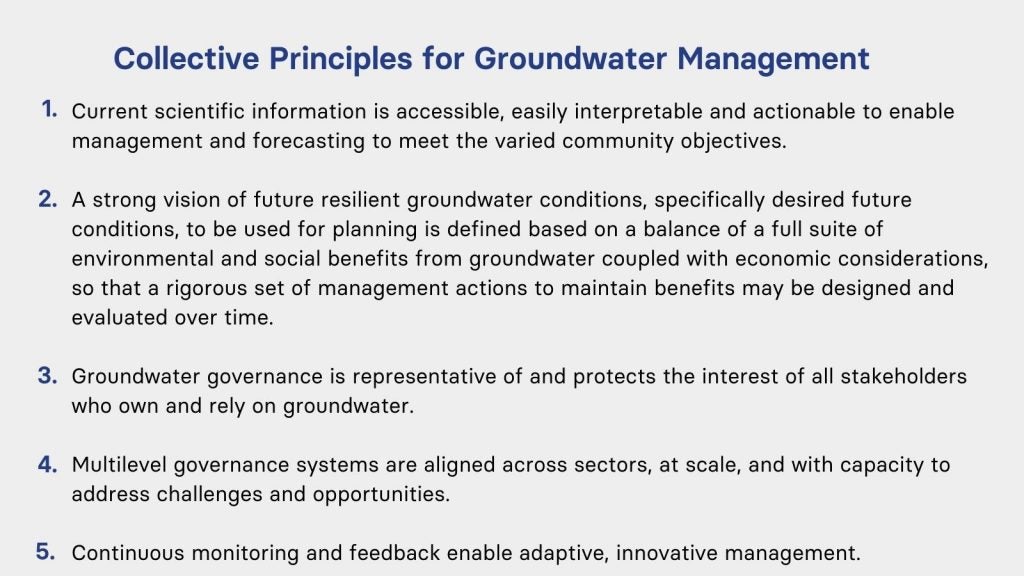

A new report by Environmental Defense Fund, Toward Resilient Groundwater Management in Texas: Identifying Collective Principles, outlines five areas where common ground exists.

In late 2020 and early 2021, EDF convened Texas stakeholders — groundwater managers, farmers and ranchers, city water managers, landowners, academics and technical experts, and conservation and wildlife advocates — to discuss the principles that should guide groundwater management.

After a series of questionnaires, interviews and meetings, these diverse stakeholders reached consensus on the following five principles.

1. Current scientific information must be accessible and understandable.

To allow for effective water management and meet diverse needs, communities need access to reliable data in a centralized, accessible place that’s easy to find.

It’s equally important that this data be understandable to people who aren’t water experts, but whose support is necessary to meet conservation and management goals.

2. There needs to be a vision for resilience — and a plan for achieving it.

By bringing stakeholders together around a common vision for an aquifer’s future, groundwater conservation districts can develop comprehensive plans that move toward shared environmental, economic and social goals. Such plans will help maintain benefits and evaluate results over time.

3. Groundwater management should protect those who rely on and own groundwater.

Groundwater conservation district boards must represent the interests of all community members who are connected to groundwater.

Most participants preferred elected district boards, since elections would be more likely to ensure that governance is representative of — and protects the interests of — everyone who owns and relies on this resource. Participants also acknowledged, however, the risk that money and politics could lead to unbalanced representation, which could likely make a hybrid model a better solution.

4. Effective groundwater management requires a system that reflects the complexity of the issue.

Texas needs a groundwater governance system that effectively balances both the management of local resources and representation of local voices with the need for consistent, aquifer-based science and policy. Some participants noted the need for consistent rules and more tools to facilitate communication among adjacent groundwater conservation districts.

5. Continuous monitoring and feedback are essential to adaptive and innovative groundwater management.

As aquifers respond to new stresses, local systems must adapt. That’s only possible with a steady stream of reliable data and a system that allows — or even encourages — groundwater conservation districts to adapt as situations demand.

Comprehensive data sharing that’s easily accessible to local officials, water stakeholders and the public can help ensure officials make the best decisions possible.

As this consensus process shows, it’s imperative that Texas update its groundwater management framework to address the growing tensions between supply and demand, and between rural and urban water users. However, state legislators have not acted.

By using these five principles as common ground to guide new policies, Texas can make real progress toward ensuring both its groundwater resources and its regulatory framework for managing groundwater are more resilient.