Natural infrastructure is gaining momentum when our country needs it most

(This post was co-authored by Shannon Cunniff and Grace Tucker)

2019 has been an unprecedented year for extreme weather, and we’re still in the thick of hurricane season. As disasters have increased, so has the popularity of using nature-based solutions to reduce flood hazard and exposure while also benefiting ecosystems and wildlife.

Along our coasts, healthy natural features – such as mangrove forests, wetlands, reefs and barrier islands – can be used to absorb the shock of storm surge, waves and rising sea levels. Further inland, nature-based features along rivers and in their floodplains can slow and retain water to help protect nearby communities.

In terms of public awareness, funding and policy, natural infrastructure is gaining steam as a critical strategy to help people and property become more resilient in the face of extreme weather.

Trending on Google

For more than ten years, the Association of State Floodplain Managers (ASFPM) has been advocating for restoration projects that build back natural buffers in riparian and coastal areas. In partnership with other professional and non-governmental organizations, including EDF, ASFPM has helped expand awareness and acceptance of natural infrastructure as a tool for flood resilience.

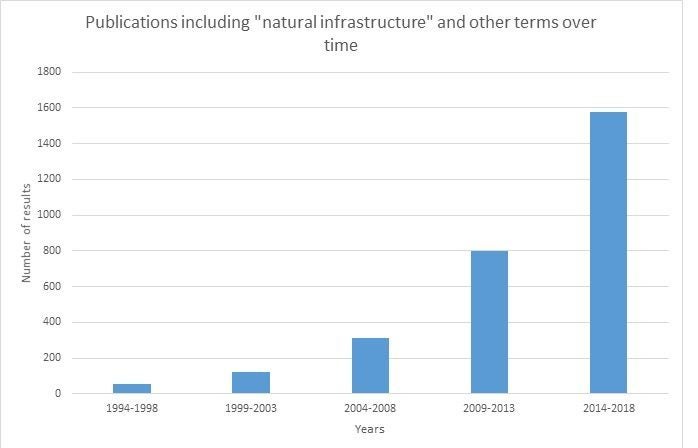

And as interest in nature-based solutions has grown, natural infrastructure is also being increasingly cited in scientific literature. References to “natural infrastructure,” “green infrastructure” and other related terms in Google Scholar essentially doubled between 2014-2018 compared to the previous five years.

Gaining steam in Congress

As more places around the country experience natural disasters, Congress is turning to natural infrastructure to address and mitigate these challenges. Water Resources Development Act reauthorizations in 2014, 2016 and 2018 have referenced nonstructural measures and green infrastructure (other terms for natural infrastructure) to reduce damages from natural disasters and most recently directed agencies to consider natural infrastructure solutions in project feasibility studies.

Before leaving for August recess, the Senate’s Environment and Public Works Committee unanimously passed their Highway bill, which included a climate title for the very first time, as well as a definition of natural infrastructure. The bill highlights the ability of natural infrastructure to mitigate the risk of recurring damage and cost of future repair due to extreme weather events.

Other proposed bills this year have also referenced natural infrastructure solutions. Senators Kamala Harris and Chris Murphy introduced legislation to advance living shorelines in the face of sea level rise; Rep. Frank Pallone introduced a similar measure in the House. Meanwhile Sen. Cory Booker proposed a bill to use nature-based solutions, such as restoring coastal wetlands, to deal with climate change.

Attracting more funding

Funding for natural infrastructure projects has roughly doubled since 2012, in part due to large programs like the National Coastal Resilience Fund that grew out of natural disasters.

In the wake of Hurricane Sandy, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation (NFWF) and Department of Interior created the Hurricane Sandy Coastal Resiliency Competitive Grant Program with a goal of reducing the impacts and threat of storm surge, strengthening coastal ecosystems and identifying cost-effective resilience tools to mitigate the effects of future storms. Policymakers in state and federal government need to work across the aisle and across the country to make natural infrastructure a priority so we can build a stronger and more resilient America. Share on X

This program has since expanded into the National Coastal Resilience Fund to cover coastal resilience projects across the country. In partnership with the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration, Shell and TransRe, NFWF administers a competitive grant program with a stated goal to restore, increase and strengthen natural infrastructure to protect coastal communities while also enhancing habitats for fish and wildlife. In 2018 alone, the program funded nearly $30 million in natural infrastructure projects with total funding increasing to nearly $70 million with matching funds.

myriad of other benefits. Photo Credit: USFWS

Innovative funding solutions for natural infrastructure are also on the rise. Environmental impact bonds (EIBs) are pay-for-performance bonds that tie investor repayment to the quality of environmental outcomes. In 2018, EDF and Quantified Ventures completed an EIB feasibility study for a marsh creation project in coastal Louisiana. Earlier this year, Atlanta and Baltimore announced their own EIBs to fund natural infrastructure projects that address critical flooding, storm water and water quality issues, while also enhancing community development and quality of life.

While this progress is encouraging, we need more attention, policies and funding for comprehensive natural infrastructure solutions from the federal to the municipal levels. Policymakers in state and federal government need to work across the aisle and across the country to make natural infrastructure a priority so we can build a stronger and more resilient America.