Climate-driven floods could displace millions of Americans. Local buyout programs could help them relocate.

By Kelly Varian, Master of Public Affairs Student at UC Berkeley

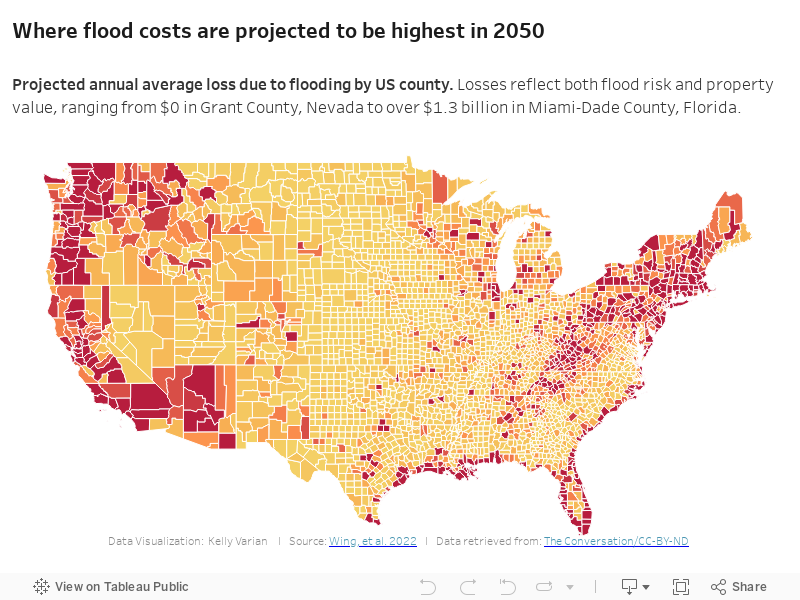

Flooding is the most frequent and costly natural disaster in the United States, causing over $30 billion in damage annually, with disproportionate effects on low-income communities. With climate change exacerbating flood risk and population growth continuing in high-risk areas, over 40 million Americans living along rivers and inland floodplains, along with 13 million more on the coasts, could see their homes inundated with water by the end of the century.

To help people move out of harm’s way, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and other federal agencies fund state and local governments to purchase repeatedly flood-damaged properties from willing owners and convert them to open space. While this process, known as a “buyout,” can save lives and lower disaster aid costs, there are numerous challenges that disincentivize homeowners and communities from participating.

The challenges that discourage flood buyout participation

The average buyout process takes more than five years to complete due to administrative complexity, a lack of capacity in local governments and funding challenges for homeowners and communities. This is too long for many households to wait for relocation and leads participants to drop out.

Even when buyouts are efficient, homeowners may not want to move, may be unable to find affordable alternative housing in a climate-resilient location or may not fully understand the risk they face. Local governments also benefit from maintaining taxable housing stock in high-risk areas, while homeowners and the federal government bear the cost of disaster recovery.

Consequently, too many flood victims rebuild their homes in floodplains and continue to expose themselves to disasters that can destroy lives and livelihoods. This drives up federal disaster aid and insurance costs, with the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) owing the U.S. Treasury $20.5 billion as of April 2022. To prevent rising costs and support national climate resilience, we need strong local buyout programs that support households and communities in the highest-risk areas.

Enable faster buyouts by pre-approving properties and establishing standing acquisition funds

State and local governments can speed up buyouts by working with communities to pre-approve homes for voluntary acquisition before disasters hit. Flood District officials in Harris County, Texas, for example, are using LiDAR technology to rapidly and economically determine eligibility for entire neighborhoods. In addition, governments can establish right of first refusal agreements with homeowners and processes to acquire properties with federally backed mortgages.

Setting up standing acquisition funds can also accelerate the processes by providing liquidity to cover the non-federal cost of FEMA buyouts or bypassing slow-moving federal programs entirely. For example, the local government in Charlotte, North Carolina has financed rapid buyouts with stormwater utility fees for decades. Other local programs leverage a variety of funding streams to buy flood-prone properties, including federal grants, state government appropriations, revolving loan funds and green bonds.

Encourage buyouts through community-based resilience planning

Pre-disaster planning can help communities align on where and when to prioritize buyouts given the costs, benefits and alternatives. Education should go beyond sharing FEMA flood maps and include climate projections, flood histories, case studies of successful buyouts and collective visioning for a more resilient future.

Providing wrap-around services through case managers for flood victims can reduce the barriers that lead to buyout attrition and support more equitable recovery. This may include pro bono legal services, financial assistance, help in finding affordable housing in a suitable location and vouchers for temporary accommodation while moving. Federal grants should be designed to cover these costs as well. Local government can explore opportunities to safely relocate residents within the same jurisdiction and consolidate municipalities to address lost tax revenue and support community cohesion. New Jersey’s Blue Acres Program provides a blueprint for highly supportive six to 12-month buyouts.

Create and sustain local programs with expanded flexible funding

Climate disasters are experienced locally and relocating people involves deeply personal decisions that reshape communities. Buyouts succeed when local governments understand their value and have the will and ability to implement them. FEMA should consider grants and technical assistance to establish or strengthen state and local flood buyout programs that account for a region’s unique natural infrastructure and political, economic and social dynamics. Such investments can complement a growing list of potential federal reforms (such as a bill to authorize the use of NFIP payments for buyouts, a pilot to speed up flood mitigation assistance and a suggestion to reduce federal aid to communities that fail to reduce disaster exposure).

Expanded flexible funding will also be needed to finance more buyouts if local programs succeed in incentivizing take-up. This may include allowing for proactive buyouts for qualified properties or reimbursement for costs already incurred. An example of innovative funding is FEMA’s Safeguarding Tomorrow through Ongoing Risk Mitigation (STORM) Act, which seeds revolving loan programs for state governments and Tribes to make their own funding decisions to mitigate climate risk.

Upfront investments should lead to significant financial savings. Cost-benefit analysis suggests expanding buyout programs in the highest-risk areas ultimately saves $6 for every $1 spent.

As a warming planet intensifies flooding in the United States and billion-dollar disasters continue to escalate, voluntary relocation could be a critical tool in our climate adaptation toolbox, but only with the proper care and attention to local program design, support and resources.