EDF and partners launch interactive Grand Canyon website

A new website from EDF, American Rivers, and Four Corners Mapping provides a special look at the Grand Canyon through an educational, interactive journey. The interactive tool invites people to take a tour through the Grand Canyon and learn how the complexities of the Colorado River crisis impact the Grand Canyon and its surrounding communities and ecosystems through words, images, and short videos. The Colorado River and those who depend on it for their water supply are facing a future of extreme uncertainty. Over the past year, reservoirs have fallen to the brink of potentially tanking due to long-standing overuse of the Colorado River and aridification. As states, tribes, the federal government, and the Republic of Mexico grapple with the dire water crisis along this majestic river, it may be easy to overlook the stretch of river in the Grand Canyon. Located between the two largest reservoirs in the county, Lakes Mead and Powell, the Grand Canyon has a front row seat to the water struggles in the Southwest.

The river management decisions made in the coming months and years will inevitably have lasting implications on determining what we value and how we use water in the Southwest. The Grand Canyon, caught in the middle of Lake Powell and Lake Mead, will directly bear the consequences of these choices.

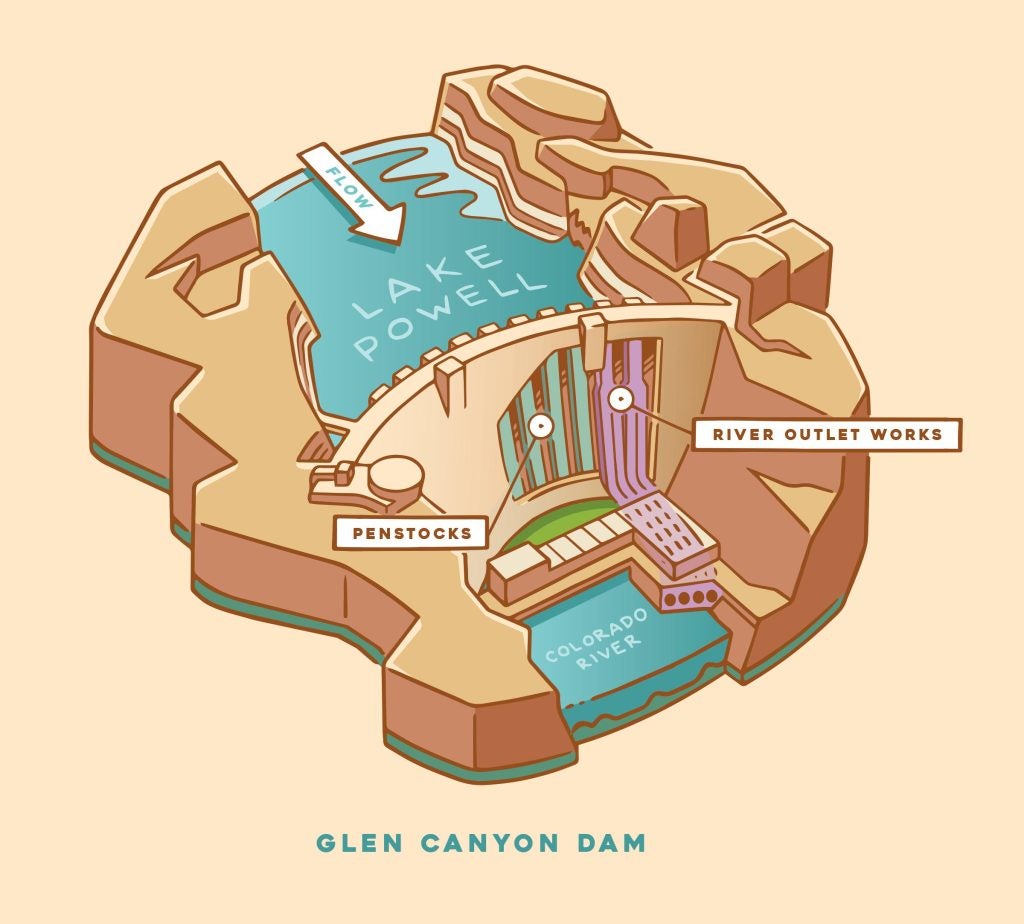

The Colorado River supports one of the biggest economies in the world and countless livelihoods depend on the water that flows out of Lake Powell, through the Grand Canyon, and into Lake Mead. Climate change, aridification and over-allocation have caused the reservoirs to decline rapidly, putting the water supply for 40 million people at risk. There is a significant risk of dropping water levels that would limit downstream deliveries for water users beyond the shortages already in place. To understand the risk of dropping reservoir levels to both the Grand Canyon and to the water users downstream of it, it is necessary to understand the workings of Glen Canyon Dam.

The workings of the Glen Canyon Dam

Upstream from the Grand Canyon sits the Glen Canyon Dam, which backs up the Colorado River to form Lake Powell. The operations of Glen Canyon Dam control how much and when, water is released into the Canyon below.

Min Power Pool

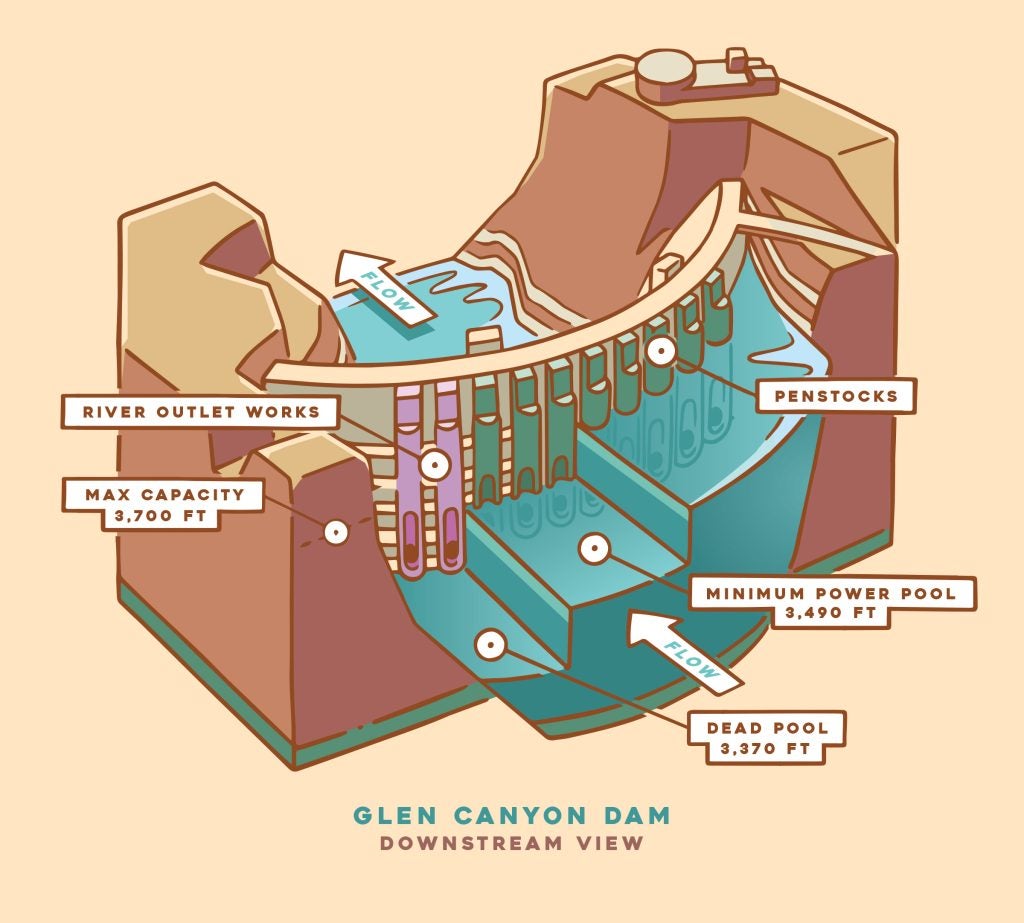

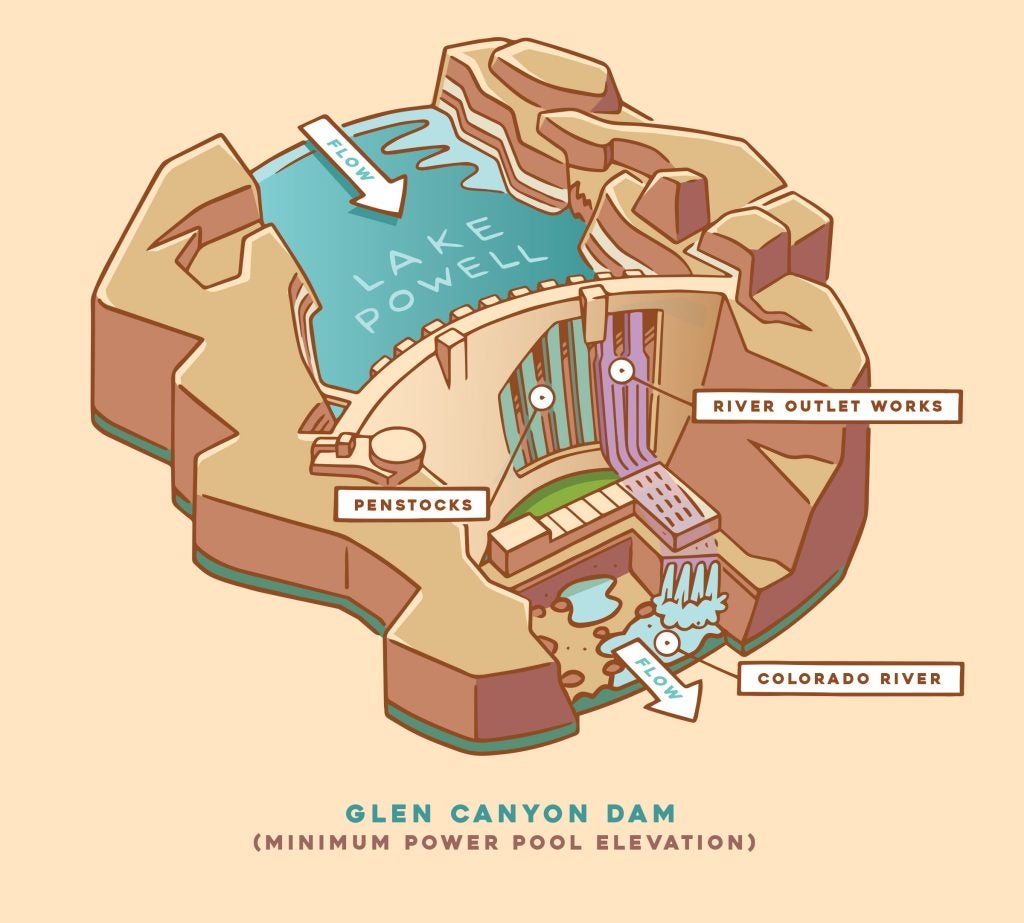

Glen Canyon Dam was designed to operate at a water surface elevation of 3490 feet above sea level or higher, also known as minimum power pool. Below this elevation, the penstocks that deliver water from the reservoir to the hydroelectric turbines, and into the Colorado River below, are not operational. If hydroelectric power generation ceases due to falling reservoir levels and water can no longer be delivered downstream through the penstocks, the only option for passing water through the Glen Canyon Dam will be to use the river outlet works, a set of 4 tubes located 100 feet deeper than the penstocks.

Relying solely on the river outlet works to pass water through the Glen Canyon Dam is a huge risk to the Grand Canyon’s health and the water security for 40 million people. The river outlet works are not intended for long-term use and there is uncertainty as to how they may fare as they work to continuously release water from behind the dam. Additionally, the outlet works have a smaller diameter than the larger penstocks, limiting the amount of water that can pass through the dam to the river and Canyon below. As water levels fall, the capacity of the river outlet works decreases, allowing less and less water to flow downstream. This scenario places the Grand Canyon and the water supply of 40 million people at severe risk.

Dead pool

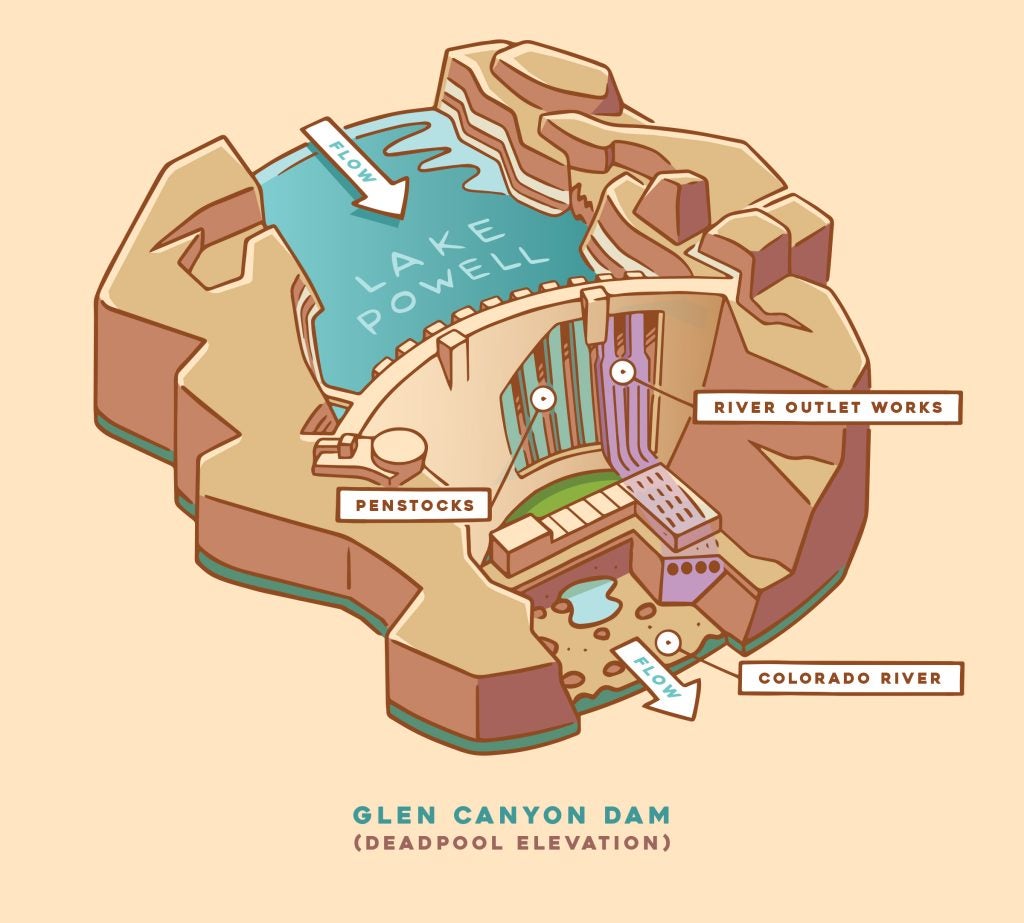

If the reservoir level continues to drop to a point where it falls below the river outlet works, then the lake will have reached what is known as dead pool. Dead pool at Lake Powell is elevation of 3,370 feet, below which water cannot pass through the dam at all. In this case, only water from tributaries and seepage around the dam will make its way to the Grand Canyon and downstream to Lake Mead.

In a scenario where the reservoir levels approach or fall below minimum power pool, water releases from Glen Canyon Dam downstream will likely be significantly curtailed. This has wide-ranging implications for Grand Canyon’s ecology, cultural connections, and recreational economy.

Collaboration and a collective water reduction

While the wet winter of 2022-2023 has provided a temporary improvement on the hydrological outlook for the Colorado River Basin, it is important to remember that a single wet year cannot balance out two decades of drought. To bring the Colorado River system into balance, it will be necessary to collectively reduce our water demand across the Basin.

The Bureau of Reclamation has already begun the decision making process that will impact operations of Glen Canyon Dam, Hoover Dam, and the future of the river flowing between them.The Bureau is currently in the process of taking steps to ensure the protection of the infrastructure at Glen Canyon and Hoover Dams through a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement that will consider proposed reductions in flows out of Glen Canyon Dam and reduced deliveries to water users from Hoover Dam.

As the Bureau proceeds with assessing viable operations at federal facilities on the Colorado River, it will be important to understand what is at risk in the Grand Canyon. The Grand Canyon is home to unique ecosystems found nowhere else in the world, supports an extensive recreational community and economy, and continues to sustain deep cultural and spiritual connections of at least 11 contemporary Tribes with historical roots in the Canyon.

As changes to the operations of Glen Canyon Dam and Hoover Dam are made to meet today’s hydrologic realities, it will be critical to identify potential risks and impacts to the Grand Canyon and its resources so we can meet the needs of the Colorado River Community without sacrificing the unmatched magnificence of the Grand Canyon.