Activating social science for flood risk and resilience planning in Louisiana and beyond.

Climate change is increasingly threatening the homes, health, livelihoods and cultural heritage of communities across Louisiana’s coast. The Bayou State is experiencing the fastest rate of coastal land loss in the country and has already lost nearly 2,000 square miles of land since the 1930s. Louisiana is taking important steps to address this risk, implementing the most comprehensive coastal planning in the nation with massive infrastructure investments for restoration and resilience.

While the state’s Coastal Master Plan incorporates the most advanced technologies and engineering, it should also include an understanding of individual and community behavior and what motivates people to act in response to climate risk – a critical component of resilience. Many factors can influence the actions people are willing to take, whether switching jobs, voting for climate policies, flood-proofing a home or business, or even choosing to relocate. That’s why we need an understanding of the unique motivations that spur individual and community action in order to equitably allocate resources.

To fill this information gap, we need scientific analysis of how people and their social networks in coastal Louisiana perceive, respond and adapt to extreme ecological changes and climate impacts. Working with partners at Cornell University, we set out to do just that.

Here is how we addressed this question and key takeaways for policymakers and planners to consider as they lead flood risk reduction and climate adaptation planning in their communities.

Two approaches to learning about coastal Louisiana communities.

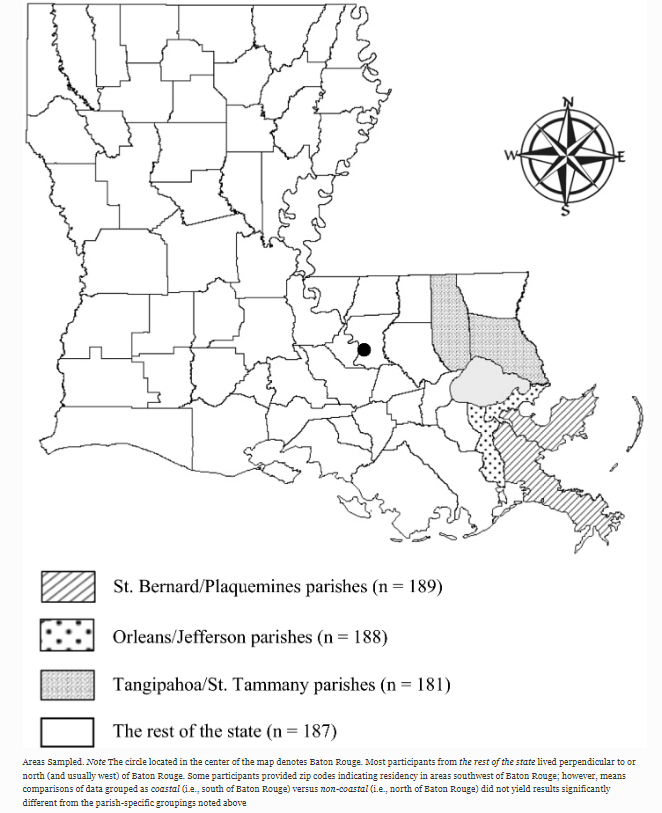

EDF and partners at Cornell University launched a two-part social science study to examine Louisiana residents’ risk perceptions related to coastal land loss and climate change.

First, we organized six focus groups in multiple parishes in southeastern Louisiana as well as in the inland community of Alexandria. Throughout these discussions, participants indicated a strong connection to Louisiana’s ecosystems and cultural history but felt they had little control over coastal land loss and their associated climate risks. Participants noted a history of mistrust in public institutions and felt both state and federal governments could do more to build resilience for coastal communities.

We used the focus group results to develop a statewide telephone survey focused on the willingness and perceived ability of residents to change their behavior to avoid or adapt to increased flood risk, coastal land loss and other climate impacts.

From nearly 800 responses, we found that people who are attached to their community are less likely to relocate, change jobs, or engage in other life-changing behaviors, even as their perceptions of flood risk increase. On the other hand, strong attachment also means people are more likely to take action to enhance community resilience, like voting for new policies, especially as perceptions of flood risk increase. Additionally, participants who had negative emotions like anger or anxiety about land loss were more willing to take life-changing actions to avoid flood risks, such as moving or changing jobs.

It is important to note that over one-fifth of participants were likely or very likely to change jobs (21%) or move within state (23.3%) or out of state (20.7%) as a response to their perceived risk. Even when participants were willing to take on life-changing behaviors, they also acknowledged that the barriers to taking this action were incredibly difficult to overcome.

Recommendations for community planners and policymakers.

Results from these studies can help generate more effective, scalable and durable solutions for communication, public outreach and coalition-building for community adaptation efforts in coastal Louisiana and beyond.

Based on our research, these are four considerations for planners and policymakers engaging in community climate adaptation planning.

1. Understanding motivations – In order to help people address their growing flood risk, we must understand the cultural and social metrics that drive their behavior. Without this information, we could inadvertently develop policies and programs that are ineffective.

2. Move at the speed of trust – Many communities are still bearing the burden of systemic marginalization, disinvestment and environmental injustice. Planners must meet communities where they are, prioritize transparent communications with communities and follow through with the necessary resources, staff and action that allow people to engage when and how they can.

3. Evaluate and remove barriers – Climate adaptation actions that are deemed to be more difficult will have less support unless they are framed as the most effective actions to reduce flood risk. Assess and remove barriers that prevent residents from changing their behavior to reduce their climate risks.

4. Start difficult conversations now – Conversations around managed retreat and strategic relocation can be emotionally fraught, challenging and time-intensive for both retreating and receiving communities. Residents may be more willing to engage in these conversations sooner rather than later, providing it means they will also have a say in the final outcome and how policy decisions impact their futures.

Overall, planners and policymakers need to utilize more social and behavioral science research as an opportunity to learn about the granularities of communities with which they work and represent. Integrating social and behavioral science into ongoing resilience efforts can help inform strategies for both individual action and larger societal action to reduce the devastating impacts of disasters and build community resilience.