Over my nearly 30 years of working on water issues in the West, I have repeatedly thought there has got to be a better way to measure how much water is used to grow the food we eat. This data is surprisingly complex, and up until now, it has been expensive to calculate.

That’s why it’s difficult to contain my excitement as this “better way” comes to fruition in the form of a new web platform called OpenET that EDF is developing with NASA, Google, the Desert Research Institute, the U.S. Geological Survey and dozens of other partners.

Using publicly available data and satellite imagery, OpenET will for the first time make data on how much water crops use widely accessible at no to low cost to farmers and water managers large and small in 17 western states. OpenET will go live next year.

The early days of satellite methods

I first learned about the possibility of using satellite data to measure crop water use in 1993 as a graduate student in Colorado, where I was researching how to improve water and nutrient management on farms along the South Platte River. Another graduate student was working on this new satellite-based method, and to earn some extra pizza money, I signed on to help with ground measurements to test its accuracy.

Even in those early days the satellite method worked pretty well. If only that data were widely available and affordable, I could have used it in nearly every water resources project I’ve worked on since, from evaluating long-term water supplies for Sacramento Valley farmers to supporting water savings projects to help salmon in California’s north coast rivers.

The ET in OpenET

The “ET” in OpenET stands for evapotranspiration, which is the process by which water evaporates from the land surface and transpires off plants. When irrigation water is applied to crops, between 60% and 95% of that water is returned to the air through ET, while the rest of the water sinks into the ground or runs off into canals or rivers and remains part of the local water system.

Managing water without ET data is like balancing your checkbook without knowing how much money you are spending day in and day out. With data from OpenET, farmers will be able to refine irrigation practices, maximize their “crop per drop” and improve their bottom line. With data from OpenET, local water managers will be able to create more accurate water budgets and design innovative conservation and responsible water-trading programs to help make farms and communities more resilient to drought and water scarcity.

“What OpenET offers is a way for people to better understand their water usage. Giving farmers and water managers better information is the greatest value of OpenET,” said Denise Moyle, a farmer from Diamond Valley, Nevada.

Sparking innovation among water managers

We’re already seeing how OpenET can drive innovation in California’s Central Valley, a region that is required to substantially reduce groundwater use over the next two decades under the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act.

In Kern County, the Rosedale-Rio Bravo Water Storage District is using OpenET data in a new online accounting and trading platform for landowners to better track their water use in a way that’s as simple as checking their online bank account. The accounting portion of the platform launched this year and the trading portion is expected to launch next year. Well-designed water trading programs can help to significantly soften the potential economic impacts of SGMA and reduce the need to retire land to reduce overpumping, according to a Public Policy Institute of California study.

There's finally a better way to measure how much water is used to grow the food we eat, says @maurice_water Share on XHelping farmers maximize “crop per drop”

Meanwhile, in Diamond Valley, Nevada, farmer Denise Moyle believes OpenET will help her move closer to answering an existential question: “How do I cut my water consumption by 50% over the next 30 years and still manage to grow a crop of alfalfa?”

Diamond Valley is a severely over-appropriated groundwater basin, prompting Nevada’s state engineer to require the region to develop a plan to reduce pumping (which is now in the courts). Moyle plans to use OpenET data to easily and relatively quickly determine how much new strategies and practices are helping her decrease water consumption.

I’m sure these early OpenET use cases are only scratching the surface of the possible ways easier access to trusted data will help transform water management in the West. As climate change continues to bring more severe droughts and put more pressure on our precious water supplies, we are going to need OpenET and many other tools, along with novel ideas from farmers and water managers, to ensure we have enough water for people, wildlife and agriculture. Our future depends on it.

Follow @OpenETdata on Twitter to stay up with the latest developments on OpenET.

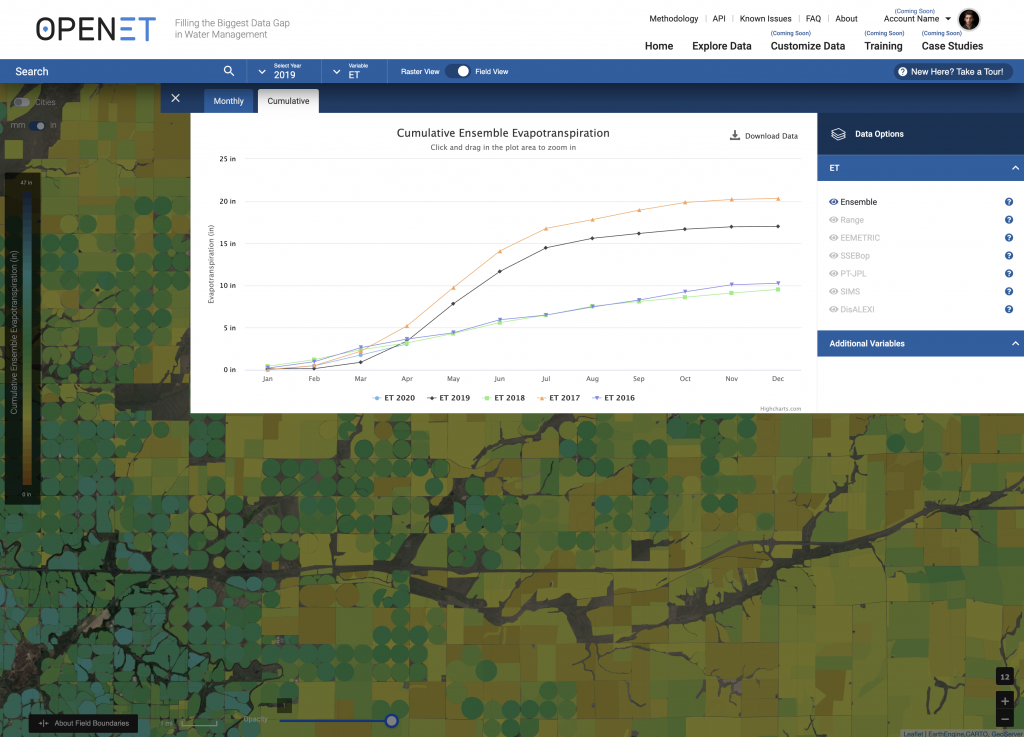

A screenshot of the OpenET interface, which shows annual water consumption data at the field scale for the past five years.

One Comment

ETo is a great tool for determining how much crop water is needed. One also needs a soil moisture reading and crop stress reading to know when the crop needs water. The statement from this article “while the rest of the water sinks into the ground or runs off into canals or rivers and remains part of the local water system” needs some context since it implies that excess irrigation is not a problem. Excess irrigation is a problem. Water that percolates into the soil below the root zone takes salts, fertilizers and pesticides/herbicides down into the water table – degrading groundwater quality for human and other life-forms use and potentially for future agricultural use. Plus, taking unneeded water from a river/stream and returning it down stream (used or unused) reduces stream flow, the return flow has increased temperature, etc. Water use charges should have tiers – with unnecessary water diverted/applied charged at a significantly higher rate.