States are turning to data and interactive maps to help residents confront and manage flood risks

2019 has been an unprecedented year for flooding, even before the start of hurricane season. Despite the number of devastating hurricanes in recent years, a new University of Notre Dame study published in Climatic Change found that most coastal residents do not plan to take preventative action to reduce damages.

In addition to speeding up the recovery process, taking action before disaster strikes can help homeowners reduce damages, save money and even lives. For riverine floods, every dollar spent before a disaster saves $7 in property loss, business interruption and death.

So how can individuals, businesses and the public sector be incentivized to make proactive investments to reduce vulnerability before a disaster strikes? The first step is clearly understanding risks—now and in the future—and having concrete recommendations for how to mitigate them.

In the past, FEMA’s National Flood Insurance Rate Maps have been the source for this information; however, these probability-based maps have not resonated with most people as they rely on the obscure “100-year floodplain” concept. Being told you live in an area that has a 1 percent chance of flooding any given year does not inspire action, nor does it reflect the reality of a changing climate.

In recent years, states have stepped up with more robust tools that give residents a clearer depiction of risks and resources for how to reduce them. Three states stand out.

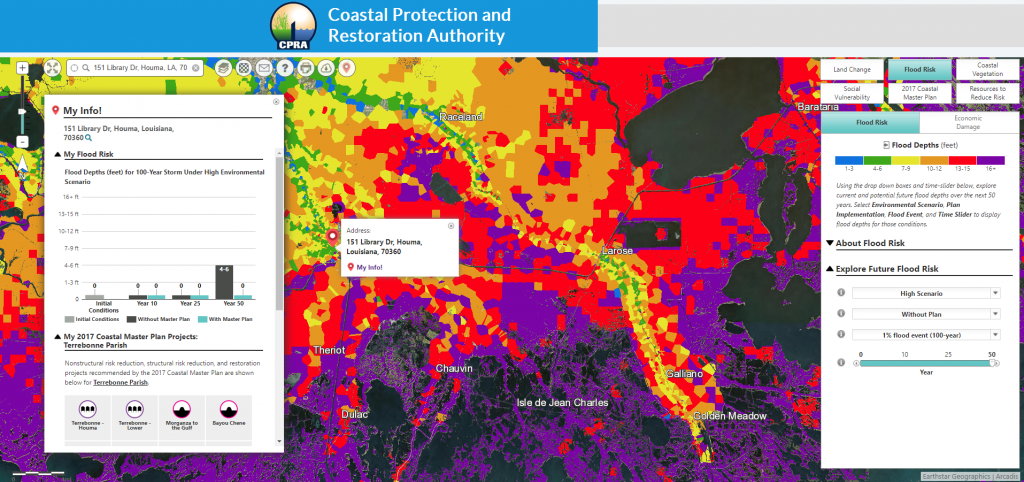

Louisiana provides 50-year storm-surge flood projections

Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan Viewer shows current land loss and flood risk and is unique in providing projections 50 years into the future. After entering their address, citizens can explore what different sea level rise scenarios may mean and determine how different flood probabilities (2 percent, 1 percent, 0.5 percent annual risk) will affect them. The integration of coast-wide data on infrastructure helps citizens determine how flooding will affect their community, and users can see how the state’s Coastal Master Plan can alter or reduce risks. The tool provides links to generic state and federal agency information on actions citizens can take, such as retrofitting or elevating homes. New tools are providing meaningful information to residents on managing their risks from flooding and other disasters. Share on X

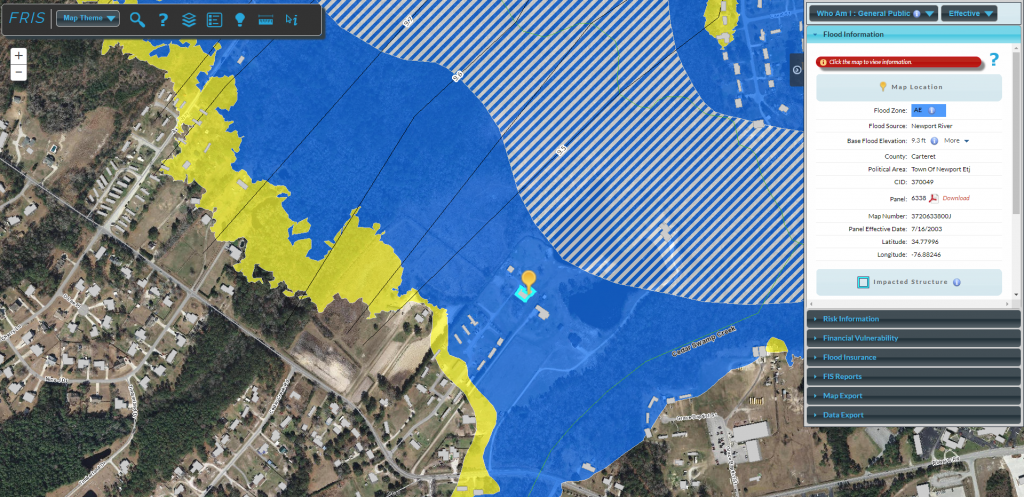

North Carolina calculates residential recovery and flood premium costs

North Carolina’s Flood Risk Information System is a residential stakeholder tool that goes a step further by providing flood hazard risk and mitigation information. The tool’s risk information describes a variety of mitigation options (e.g., elevation, relocation, wet-flood proofing, utility elevation, and levees) and estimates costs. Based on the building value, a calculator helps homeowners determine if they have the resources to recover if property is destroyed, and a flood insurance calculator helps them understand the expected monthly premiums. It does not, however, reflect changing flood probabilities based on recent floods and a changing climate.

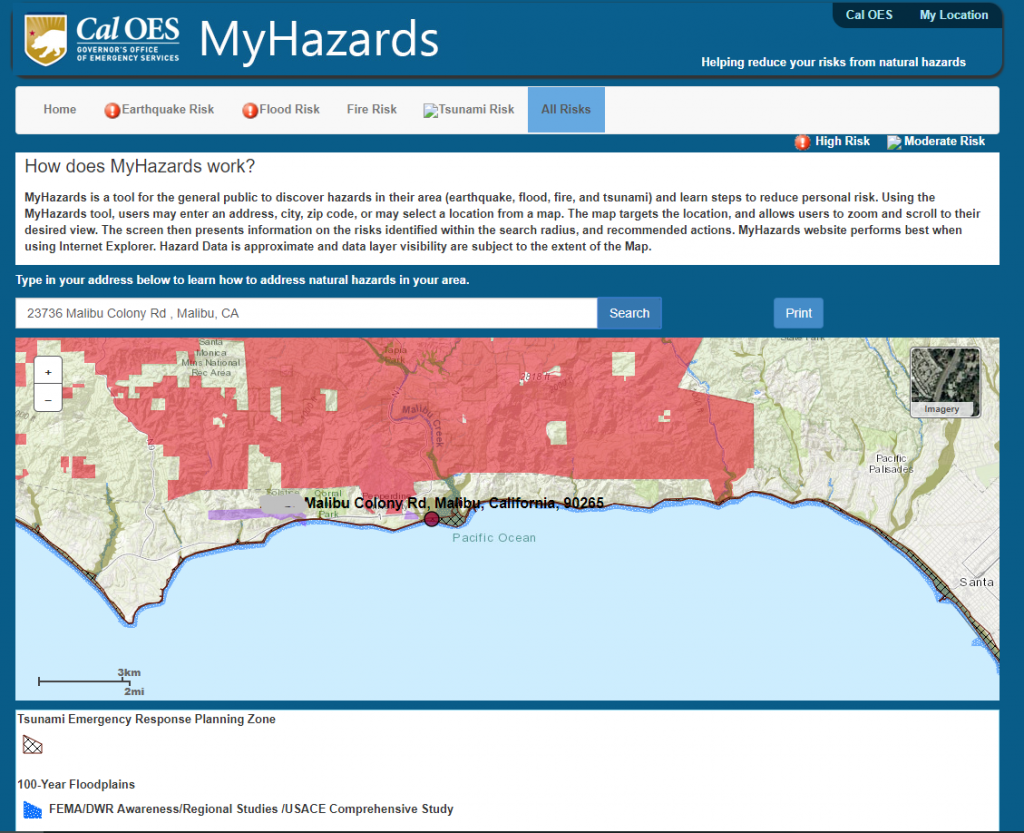

California maps out multiple hazards and provides recommended actions

California’s MyHazards tool lets users see all the natural hazards for a specific address – earthquake, flood, wildfire and tsunami – and identify steps to reduce risks. For areas in or near a flood zone, it provides options to reduce injury, loss of life and damage to home and property, specifying which are recommended, optional and not recommended. In looking at all potential risks and seeing mitigation actions, a property owner can determine where one action reduces damages from more than one hazard. What it fails to do is reflect changes in risk due to sea level rise, increased inundation and erosion.

Building socio-economic and environmental resilience to floods will require an integrated set of local, state and federal programs, as well as individual actions by property owners and businesses. These states, as well as companies in the private sector, have provided models that others can build on to provide meaningful information to residents on managing their risks from flooding and other disasters.