It’s hard to know what to make of the recent monarch butterfly news. On one hand, the western population of monarchs native to California is down 86 percent this year compared to last – reaching a dangerously low threshold that puts them on the brink of extinction. On the other hand, the eastern population that migrates east of the Rockies and overwinters in Mexico is up 144 percent – the highest count since 2006.

With the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service currently weighing the need to list monarch butterflies as threatened or endangered, the stakes are incredibly high to understand what these population trends mean for the iconic species.

So how do scientists explain these apparently conflicting population numbers?

Trends are more important than a single data point

It’s critical to understand that every species’ population has natural variations from year to year. For a number of reasons, there are good years and bad years.

Maybe flowers bloomed at just the right time to make ample food available one year. Or perhaps a big storm made migration particularly hard another year. That’s why it’s so important to look at population trends over many years to know if a pattern of bad years is outweighing a few good years. If we act now, we can change the trajectory for both monarch populations, before it’s too late. Share on X

It’s just like climate change. The polar vortex most Americans experienced last week was a weather event – a very cold week. But the Earth’s climate continues to warm rapidly when scientists observe global average temperatures over recent decades.

Just like we would celebrate a nice weather report, we should celebrate any good monarch population report, but we should also remain prepared for bad weather, especially as climate change creates a new abnormal for humans and wildlife alike.

Science still shows monarchs are at great risk

If we take a step back and look at the population trends for both the western and eastern populations, the pattern is clear: one good year doesn’t fix the problem.

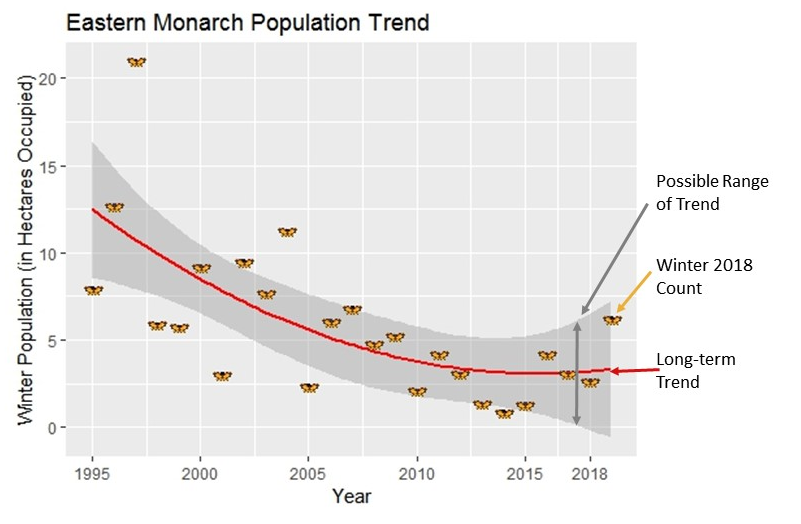

In the chart above of the eastern population, the pattern over the last few decades clearly shows an overall decline. This winter’s monarch population increase is great news, but even the best models cannot tell if this is a change in the population trend or just a blip outside of the pattern.

We need several more years of high monarch population counts before the model would confirm that the eastern populations of monarchs is, in fact, recovering.

Out West, one more bad year could be the end for the monarch

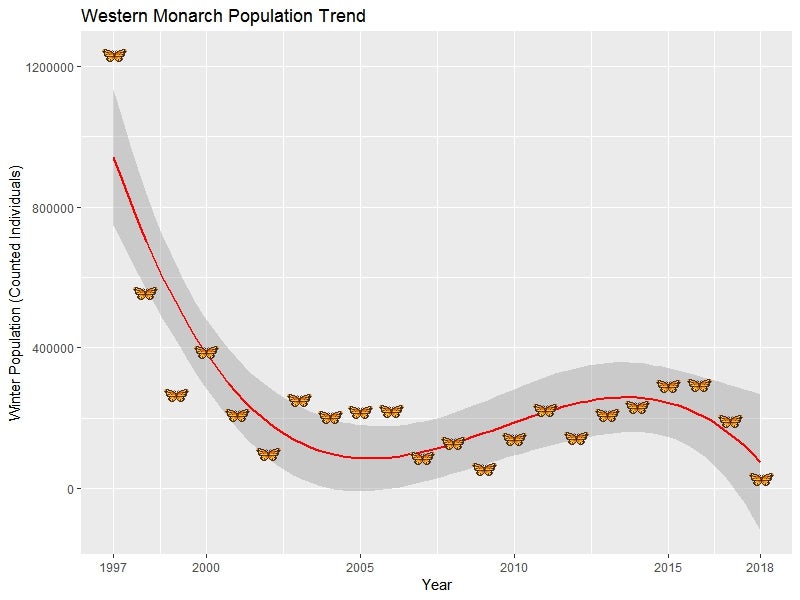

The western population is a different matter entirely. While the overall trend is bad (the last three years have seen massive declines), the most recent report was especially concerning.

That’s because studies show that 30,000 butterflies is the average population needed to avoid a complete collapse of the western migration, and extinction of the entire western population. As you can see from the chart below, the data trend is pointing in that direction.

In short, the science shows the western monarch population balancing delicately on the precipice of extinction. One more bad year would likely mean the end of the western monarch.

But all hope is not lost

We can’t control the weather, but we can build resilience. And we need to do it fast.

We can build resilience in both monarch populations by working with key partners on working lands across America to make more monarch habitat available throughout the species’ range – from the Central Valley of California to the Corn Belt in the Midwest. My colleagues are already working with farmers and ranchers on the ground in Iowa, Missouri, Texas and California to help provide technical assistance to those willing to conserve habitat for monarchs, including planting new milkweed and wildflower habitat.

We’re working to ramp up these conservation activities quickly to help build more robust monarch populations. This will help us move beyond one-off good years and begin to see a population data trend pointing upwards.

If we act now, we can change the trajectory for both monarch populations, before it’s too late.

6 Comments

Great Post, I really appreciate to blogger for this useful information. Keep sharing.

There is no man made climate change..temps on mars are differing about the same as earth..cycles of the sun. California has wiped out Milkweed ..and over wintering areas. However in the Midwest and mid south, there is an active and growing outcry to plant Milkweed for the Monarchs and its helping, it is estimated that more Milkweed was planted last year in 2018 than in the past 5 years combined.

Stop repeating the Mars warming hoax. The sun is in a coolong trend that has been well documented. Inferring that all the planets are warming is an outright lie.

The species itself is in no danger of imminent extinction. If you search Google, you’ll see that Monarch butterflies have been invading other countries and continents, from Bermuda and Spain to Polynesian islands and Australia. This is not the picture of a species bordering on extinction. Meanwhile I do not counsel indifference to the North American populations.

Sounds reasonable to me, Joe! Before Iowa became a corn/bean desert, many vried native plants in the roadside ditches and farmsteads, pastures. The Wild rose, Iowa’s state flower is harder to find.

You cannot compare Mars and Earth. Different atmospheres…different distance from the sun…different size…no plants to absorb CO2…no water at the surface on Mars.