Will we be prepared for the next natural disaster? Let’s make sure the answer is “Yes.”

It’s hard to believe it’s been nearly a year and a half since Hurricane Matthew delivered devastating floods across eastern North Carolina. With so many families and communities still recovering from that storm, the thought of having to prepare for the next one is daunting, but it’s a necessary reality.

This month, a group of North Carolina state legislators will convene in Raleigh to discuss how to spend the state’s remaining federal disaster relief funds provided in the wake of Matthew.

In addition to the needs of still ongoing recovery efforts, the North Carolina House Select Committee on Disaster Relief is expected to begin exploring investment opportunities related to flood control and risk mitigation.

Traditional approaches won’t cut it

As both a resident of North Carolina and a practitioner of streams, I’ve spent a great deal of time reflecting on why Hurricane Matthew caused so much damage. In the weeks following the storm, I wrote about it in a piece for Ecosystem Marketplace, in which I made the case that North Carolina’s rapid growth changed the natural course of our state’s waterways in ways that degraded some of the critical flood protection services they provide.

With another year’s worth of reflection on the natural disaster, I keep coming back to those two words, “natural disaster,” which lie at the heart of the matter.

Hurricane Matthew was a disaster. It was sudden, it was tragic, and it caused great damage and loss of life. It was also truly a force of nature. But nature can also provide us with important opportunities to reduce flood risks, improve the resiliency of our communities, and help ensure we are all better protected in the future.

I expect that our legislators will come up with several suggestions for how to spend our disaster relief funds. Traditional approaches like buy-outs, relocations, and engineered solutions like levees and dams are all likely to be on the table. But what we really need on the table is more nature-based solutions.

Ensuring a safe and prosperous future

In order to make sure we are better prepared for the next storm, we need to take a close look at our rivers, streams and floodplains to make sure they are capable of handling the next deluge and keeping our communities safe.

Will we be prepared for the next natural disaster? Let’s make sure the answer is “Yes.” Share on XIf we do this, we’ll likely find that many of our waterways are not equipped for the next storm, which is why I recommend that some disaster relief funds are dedicated to restoring our state’s waterways. Instead of levees and dams, we need broad vegetated buffers and large floodplains that can hold water and handle surges without flooding the surrounding communities.

Bonus: These forms of natural infrastructure are oftentimes more affordable.

Double bonus: These stream features also improve water quality, wildlife habitat, and recreational opportunities.

A case study from Wake County

In October 2016, just two weeks after Matthew, I visited a stream restoration site outside of Raleigh in Wake County, North Carolina. The site provides a good example of how stream restoration can help minimize the damages of hurricanes and severe flooding.

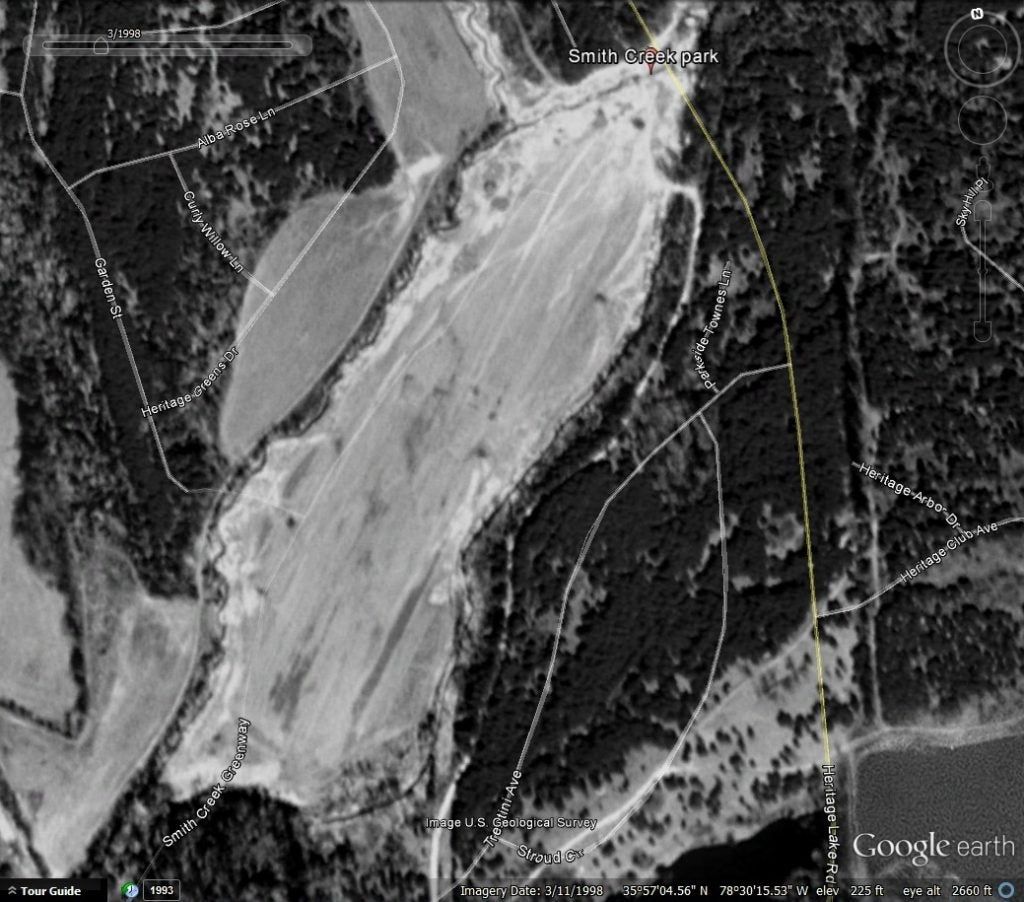

The site is positioned between Smith Creek and Austin Creek – an area converted from farmland to housing development in the early 2000’s. As you can see in the aerial images of the site below from 1999 (top) and today (bottom), Smith Creek (upper wooded area), and Austin Creek (lower wooded area) are now bordered by houses with soccer fields between the two.

Despite being located in a developed and still developing region, both streams have broad vegetated buffers and large floodplains, thanks to restoration efforts which focused on reconnecting the streams with floodplains.

This restoration clearly paid off when Hurricane Matthew hit the area. There was minimal evidence of erosion and significant evidence (from branches and other woody debris) that the surge of water exited the channels and flooded the floodplains as designed. Ultimately, the restoration design reduced flooding impacts on the communities next to and downstream of Smith and Austin Creeks.

As our legislators continue their work to support our communities in recovering from Matthew and preparing for the next storm, they should be looking to case studies like this, and focusing investments and policies on restoring the health of our state’s degraded waterways. It’s the best way for us to ensure a safe and resilient future for North Carolina.