10 years later: What we have (and haven’t) learned from the devastating Aliso Canyon methane leak

This week marks the 10th anniversary of the Aliso Canyon methane leak — the largest natural gas leak in U.S. history that pumped more than 100,000 tonnes of the potent greenhouse gas methane into the atmosphere. Many have compared the resulting environmental damage to the catastrophic 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

The leak occurred at an underground gas storage facility northwest of Los Angeles and went on for over 100 days before eventually being plugged.

By that time, thousands of residents were displaced from their homes and reported experiencing severe nose bleeds, headaches and other health impacts. Studies on the longer term health impacts of the disaster are still ongoing, but a recent study indicated that pregnant women living near the facility were significantly more likely to have babies with low birth weight. Meanwhile the climate impact of the gas emitted during the leak is similar to that of a large European country’s annual greenhouse gas emissions.

10 years later: What we have (and haven’t) learned from the devastating Aliso Canyon methane leak Share on XThe gas company responsible for the leak ultimately agreed to pay out over $1 billion to settle lawsuits regulated to the damages. The facility has remained in operation in order to meet the region’s energy demands but with new regulations to help prevent another incident. Will it be enough?

The leak exposed significant vulnerabilities in the way the United States’ natural gas system is managed — drawing attention to both the impacts of mega leaks at storage facilities, as well as to the millions of smaller leaks occurring everyday across the entire natural gas supply chain.

So what has changed since the leak drew international attention to the methane problem?

New rules for gas storage, but largely on the industry’s terms

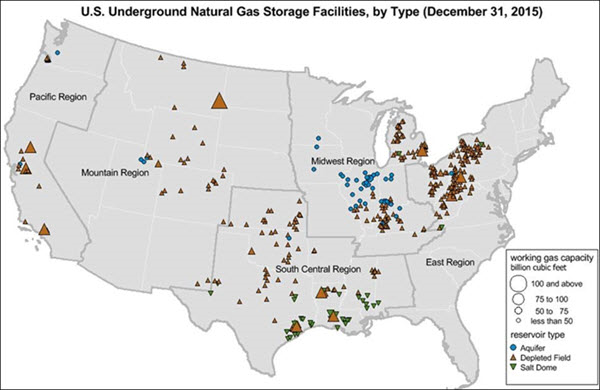

The Aliso Canyon gas storage facility is not unique. It’s one of 400 facilities across the country that store about half of the country’s natural gas. For many years, there was effectively no federal oversight and only minimal state oversight of these facilities, which has had fatal consequences.

The international attention generated by the Aliso Canyon gas leak triggered the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration to adopt new recommended practices, developed by industry, for gas storage sites in 2017. And in fact, earlier this month, PHMSA adopted industry’s updated recommended practices for gas storage, which feature significantly improved risk management and emergency response planning — good news worth celebrating.

However, because even these improved practices were originally written as voluntary industry best practices and not meant to act as regulation, they can be vague, ambiguous and difficult to enforce. And the recommended practices are not easily accessible since industry groups charge a fee to view them online. PHMSA should make access to these recommended practices publicly available. And its critical that it develops and enforces more comprehensive regulations for gas storage facilities to reduce risks to our health and our environment.

Further, the underlying law giving PHMSA authority to oversee gas storage creates an arbitrary bifurcation in safety regulations. States have the ability to go beyond PHMSA standards for facilities that store gas for use in that state, but can’t apply those same standards to a facility if that gas is sent elsewhere. There’s essentially no difference in the operations of these interstate vs. intrastate facilities — they all can experience single points of failure leading to catastrophic blowouts. In fact there are some 17,000 wells that feed these storage sites and, as they age and corrode, many are at risk of failing. While it’s good that there are improved federal guidelines for safer gas storage, it’s clear we still need a more coherent plan for upgrading facilities and managing these long term risks.

It’s unclear whether any of that will happen anytime soon. Under the Trump Administration, PHMSA has been hemorrhaging staff. There are nearly 50 job vacancies in the department, including key experts and people at leadership levels, and enforcement actions have plummeted to record lows. Without staff and resources, it’s highly unlikely the agency will be able to achieve its mission of protecting people and the environment from the risks associated with energy transport and storage.

More scrutiny on methane – for now

Since the leak, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has also made significant progress to limit leaks at hundreds of thousands of oil and gas production sites across the country. Cumulatively, emissions from the oil and gas industry add millions of tons of methane and other toxic smog-forming and cancer-causing pollutants into the atmosphere each year. Studies have revealed that unchecked pollution from oil and gas facilities has caused thousands of premature deaths, asthma attacks and hospitalizations and are responsible for over $77 billion in annual health costs. Over the past decade, leaky equipment and other wasteful operations at oil and gas facilities have led to nearly 90 million metric tons of wasted gas.

While some states have led on efforts to address oil and gas methane pollution (California, Colorado, New Mexico and Pennsylvania) many states have not yet adopted cost-effective practices that can reduce energy waste and save lives. And despite the known health and environmental impacts, as well as the massive waste of American energy resources, the Trump Administration is attempting to demolish these federal methane protections and has even said it will no longer track greenhouse gas emissions altogether.

- Want to take action? The deadline to provide public comments regarding proposed changes to the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program is open through Nov. 3, 2025.

In the decade since the Aliso Canyon disaster, oil and gas companies have demonstrated that controlling emissions isn’t just feasible, it’s economical. EDF estimates that since the first oil and gas emissions regulations went into effect in 2012, companies have saved around $2.6 billion worth of natural gas — demonstrating that with the right practices, it’s possible to safely and economically manage methane as we transition to safer forms of energy.

As super storms, wildfires and other severe climate impacts wreak havoc on communities across the globe, the anniversary of one of the worst emissions events in our nation’s history, and the actions that have unfolded since, should serve as a reminder that controlling methane is crucial for our climate, for energy security and our health.