Carbon dioxide injection wells require deliberate and protective liability rules

Post-closure liability management may be a rather obscure part of the burgeoning carbon capture and sequestration , or CCS, industry. But more and more lawmakers and regulators in U.S. states and around the world recognize it’s an important piece of their climate change agenda.

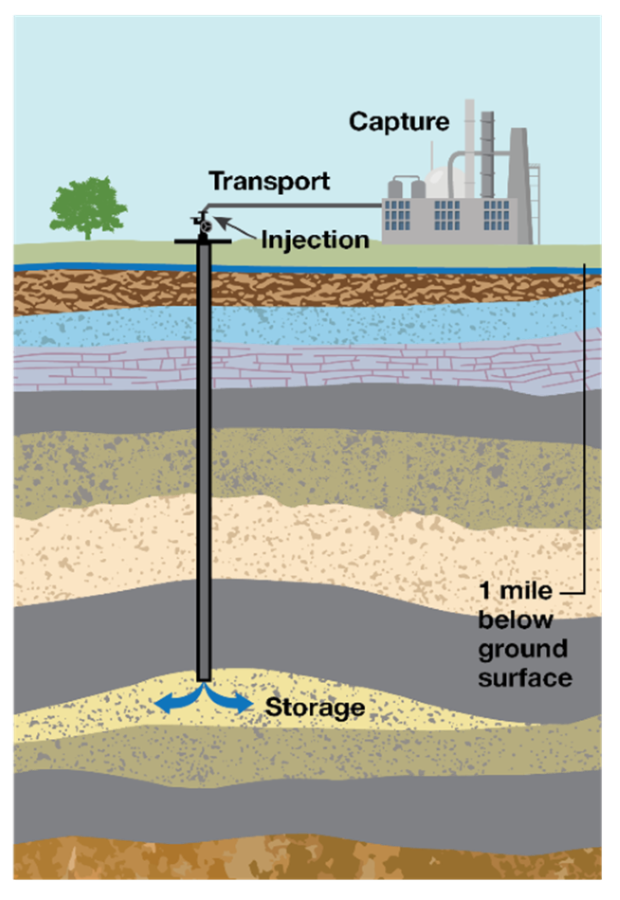

That’s because many experts, including the International Energy Agency, estimate that — even as far out as 2070 — more than 90% of the tens of billions of tons of carbon dioxide captured globally will need to be injected deep underground where it can be permanently stored.

https://blogs.edf.org/energyexchange/wp-admin/post.php?post=23376&action=edit Share on XPermanently is a long time — an outcome the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concludes can occur if storage sites are properly sited and operated. And it raises questions about long-term responsibility and oversight of storage facilities. Concerned with limiting their risk to a more narrow timeframe, some companies are actively seeking legislation in likely CCS regions that would absolve them of any long-term liability and pass the risk to the public.

This isn’t the right solution.

Post-closure liability simply refers to who’s legally and financially liable if something goes wrong at a carbon storage facility once it’s been sealed and has received an official certificate of closure — which could be many decades after a project starts. Up to the point of the closure, liability rests with the operator running the project. Unless modified by state law, the general presumption is that an operator is responsible for the impacts of their actions — a liability standard the oil and gas industry is held to for the life of their wells. Aiming to spur commercial investment certainty, legislatures around the country and the globe are modifying this general principle to varying degrees. Some transfer responsibility for any and all incidents post-closure to governments and taxpayers. Others establish various limitations on transfer.

EDF has been working on the technical and regulatory issues surrounding CCS for years, and we teamed up with Great Plains Institute to provide legislators and regulators who are wrestling with this issue a framework to guide their deliberation.

Download the EDF/GPI Liability Framework

The good news is that properly selected, managed and closed carbon storage facilities have a very low risk of problems, and thus liability, over long time horizons. The IPCC has estimated that, done right, a well should safely sequester carbon dioxide for 10,000 years or more. Over time, it chemically binds to the rock.

Yet the risk of incurring long-term liability plays a very important role in ensuring operators do, in fact, select good locations, design and execute the project well, and follow best practices that minimize the risk of failure. Removing all liability removes a basic incentive to do it right, not to mention reducing public trust in the industry’s confidence in their work.

With the insurance and other risk-management tools available today, liability relief simply isn’t needed for commercial investment to continue. However, as governments continue to consider their options to offer this release from liability, it’s vital they avoid inadvertently incentivizing shoddy work.

Identifying a permanent public steward for these projects is logical and reasonable. But such transfers should not shift liability for problems caused by operator actions. Our framework outlines four key exceptions states should consider for any liability relief legislation to protect taxpayers and incentivize companies to build the best projects possible.

The exceptions would apply if:

- the operator violated a duty imposed by law or regulation prior to the certificate of closure

- the operators provided deficient or erroneous information that the regulators used to approve the closure

- the regulator determines the operator is responsible for fluid migration that causes or threatens endangerment to drinking water sources

- the regulator determines there is not enough money in escrow or storage trust funds to cover costs

Climate change is an urgent threat, and fully solving it will likely require carbon sequestration at massive scale. But we cannot make rash decisions that spark unintended consequences. If carbon sequestration is to live up to its potential as a climate mitigation tool, we have to be smart about how we regulate it. Our framework is a sound place to start.