Latest research leaves questions about some sources of atmospheric methane unsettled, but need to act remains

A pair of new scientific papers published in the journals Nature and Science argue that levels of so-called fossil methane coming from naturally occurring sources — underground seeps, volcanoes, and so forth — are much lower than previous estimates, and that human-made emissions from the fossil energy industry account for a much larger share of the global methane budget.

The widely reported findings arrive in the midst of a robust debate among researchers in which a great deal is still unsettled. Whether these latest findings eventually prove correct remains to be seen. But the ongoing discourse leaves no doubt about the continued need to dramatically reduce the vast amounts of methane that we know are currently emitted by oil and gas production and distribution.

Running debate

Atmospheric concentrations of methane have increased about 150% since the beginning of the industrial revolution, due mainly to anthropogenic sources including oil and gas production, coal mining, agriculture and landfills. Since 2007, however, the increase in concentrations has been particularly steep, accounting for roughly 13% of the total.

The scientific debate about the specific sources responsible for this global accelerated increase since 2007 has received public attention. In part, this is because some have suggested that the U.S. shale gas boom could be responsible for a large proportion of the increase (e.g., here), but the science is not sufficiently settled to determine if that is in fact true. The Global Carbon Project was set up to integrate and reconcile data collected by the science community to investigate issues such as this.

Latest research leaves questions about some sources of atmospheric methane unsettled, but need to act remains Share on XTwo new papers are focused on the related but separate question of the size of current (or baseline) fossil fuel industry-related methane emissions — as opposed to whether the U.S. shale gas boom has contributed to the global methane rise since 2007, and if so how much. The question of current emissions rates is the same that EDF addressed at the national level in the U.S. through a coordinated series of measurement campaigns over five years, which concluded that EPA’s estimate of oil and gas supply chain methane emissions was 60% too low. That effort was subsequently expanded to collecting similar data in other countries.

The latest studies

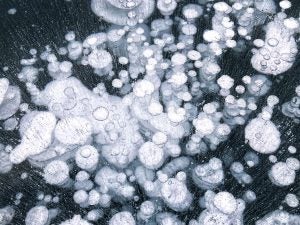

Isotopic fingerprinting allows scientists to distinguish methane created a long time ago (i.e. fossil methane in oil and gas deposits and coal seams) from recently created methane (e.g. wetlands and cows) by comparing the chemical structure of methane molecules in the atmosphere (isotopic signature).

However, distinguishing whether the source of “old” fossil methane in the current atmosphere arrived ‘naturally’, or as the result of fossil fuel production and use is not easy. To address this question as to the source of fossil fuel methane, the authors of two recent papers looked at the amount of methane trapped deep inside a glacier in Greenland hundreds of years ago, before fossil fuels came into wide use. Any fossil methane trapped in those ice cores could only have come from natural sources, which they assume have remained fairly constant over time.

By subtracting the amount of naturally occurring fossil methane from present day levels the remainder can be assumed to be the result of human activities — principally use of oil, natural gas and coal.

The Nature paper estimates that methane emissions from global fossil fuel value chains are 25-40% higher than previous studies have suggested. The related paper in Science uses the same approach, but extends the analysis further into the past. It arrives at a similar conclusion.

Conflicting evidence

The devil, of course, is in the details. The specific radiocarbon isotope methane measurements used in the two papers provide an immediate global picture, but they are highly complex in terms of data collection and interpretation.

The estimates of natural methane seepage derived in both papers stand in stark contrast to a large body of present-day direct measurements of methane emissions at geologic seeps, which indicate the volume of fossil methane escaping naturally is an order of magnitude higher than what the new research suggests. These direct measurements use well established methodologies to estimate emissions from seeps, but the results need to be extrapolated globally to determine total emissions.

At this point, there is no agreement on how to reconcile these conflicting results. For now, we think it’s too early to draw larger conclusions.

More mitigation action needed

Whether the upward revision of current day fossil fuel industry methane emissions in the two papers represent reality or not, it does not change the fact anthropogenic methane emissions — driving more than 25% of the current warming — are too high.

Recent scientific studies clearly indicate that mitigating anthropogenic methane emissions is important for slowing the rate of warming, and the oil and gas industry provides major opportunities to doing so cost effectively and rapidly.

Given that cost effective measures exist in the oil and gas industry to mitigate a large portion of these emissions there is every reason to do so as soon as is possible.