Getting dangerously creative with oil and gas wastewater

The oil and gas industry has a massive wastewater problem. And if the growing dialogue about new ways of dealing with it are any indication, it may get worse if we aren’t careful.

Cost concerns, pressure to conserve water, and other factors have led some oil and gas companies to consider new ways to manage or repurpose wastewater – including using it to irrigate crops. That could create more problems than it solves.

Managing the massive amount of oil and gas wastewater has been a challenge for energy companies for generations. Some wells produce up to 10 times more wastewater than oil. In the United States, companies produce nearly 900 billion gallons of wastewater a year. That’s enough to fill over 1,000 football stadiums.

Ongoing Risks

Oil and gas wastewater is often many times saltier than sea water – and can ruin soil for generations if large amounts spill or leak during storage or transport. In fact, landowners with a long history of oil and gas production on their lands know that a wastewater spill can cause much more long term damage to their land than an oil spill.

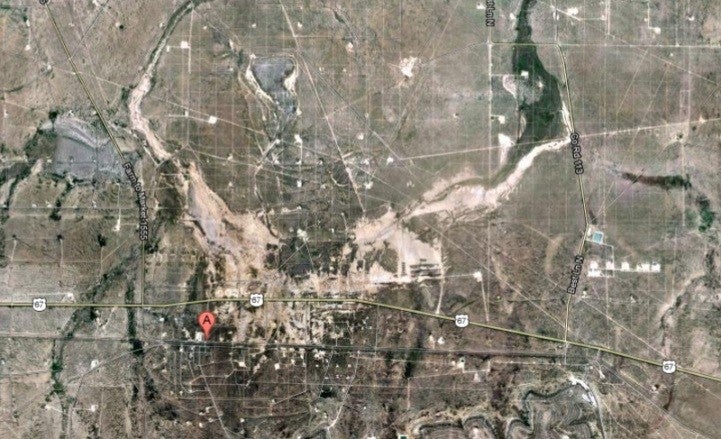

Case-in-point, in the 1920s oilfield wastewater was managed by releasing it directly onto West Texas soil, before the industry and regulators fully realized the negative consequences of this practice. It created the Texon Scar, a patch of dead earth so large it can be seen from space.

Beyond salt, this waste can contain any number of nearly 1,600 chemicals that are either present in groundwater or known to be used in the well construction process – chemicals ranging from ethylene glycol (antifreeze) to hydrochloric acid. And yet, regulator-approved chemical detection methods only exist for about a quarter of them. This means that we can’t know if certain toxic chemicals are present, and the energy companies can’t say they aren’t.

Beyond salt, this waste can contain any number of nearly 1,600 chemicals that are either present in groundwater or known to be used in the well construction process – chemicals ranging from ethylene glycol (antifreeze) to hydrochloric acid. And yet, regulator-approved chemical detection methods only exist for about a quarter of them. This means that we can’t know if certain toxic chemicals are present, and the energy companies can’t say they aren’t.

Quakes, Cost and Climate

Industry’s most common solution to this deluge of wastewater has been to pump it into specialized disposal or enhanced recovery wells, but a number of factors have companies (and sometimes regulators) looking at alternatives.

One reason? A dramatic increase in the number of earthquakes in some oil and gas regions, has raised questions about this once tried-and-true disposal method. In Oklahoma, for example, regulators limited wastewater disposal volumes after a rash of earthquakes shook the region (the number of quakes dropped afterwards).

And disposing of wastewater can be expensive. Depending on the well and its location, water management – including trucking, treatment, and disposal – could be the single greatest expense of the operation.

Finally, there’s no doubt that concerns about fresh water use and protection will only increase as climate change exacerbates prolonged droughts in a number of key energy-producing states like Texas, California, New Mexico and Oklahoma.

What now?

All of these factors have insiders looking for new ways to repurpose wastewater, but perceived near-term pressures should not push decision-makers towards options that could create new, long-term risks to water and other resources.

Some options, like recycling industry’s wastewater to fracture new wells, are viable with current management practices – assuming leaks and spills are minimized. Others, however, like using treated wastewater for agricultural purposes, come with a number of risks and unanswered questions, like: how can companies and regulators ensure the water is “clean enough” for new uses? And what are the long term impacts to the soil and crops? What about other health or toxicological impacts? We don’t know, and that’s the problem.

Moving forward with new management practices before we know more about what’s in wastewater could be dangerous; the Texon Scar is the perfect example of that. Operators in the 1920s didn’t know their decision to release wastewater onto soil could be problematic, but that lack of information resulted in a vegetative dead zone that has lasted for nearly a century despite countless hours and dollars spent on restoration.

Our advice is fairly simple: not so fast. Before industry adopts (or regulators allow) new uses for this polluted water, we need to learn a lot more about what’s in this water and how it could threaten human health and the environment. In other words, we need to look before we leap, and everyone’s eyes – companies’, regulators’, scientists’ and citizens’ – need to be wide open.

EDF is certainly not the only group advising caution. In the last issue of Air and Waste Management Association’s magazine, several academics and industry experts outlined the various challenges of new wastewater uses. And the Ground Water Protection Council has announced a project to define the types of important questions state regulators need to be asking and answering now to make smarter decisions on produced water in the future. That’s good. We NEED to spend time getting this right. Let’s not leap before we look.

One Comment

That’s a good sign though.