Warning: Unnecessary Pipelines Could Leave Consumers Holding the Bag

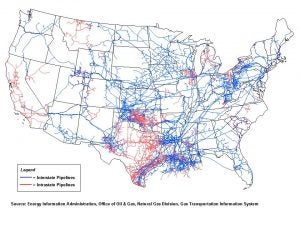

New oil pipelines are very much in the national spotlight. There’s been less attention on big pipes to transport natural gas. So far, debates over gas pipelines have been mostly local and regional affairs, even though there are dozens of gas pipeline applications pending before the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). The traditional concerns with both types of pipelines are largely the same: safety, routing, and environmental impacts.

But even before you get to those questions, there’s a more fundamental one we should be asking: Have the pipeline developers established a true need for the project?

In some cases, the answer might be yes. But in other instances, there are strong reasons to believe the “need” for new gas infrastructure is exaggerated by pipeline developers with corporate ties to the local utilities signing contracts to pay for the pipe whether or not they end up using the gas. Utilities can do this because – by law – the bill for that infrastructure ultimately gets passed through to captive ratepayers.

One example is the Access Northeast Project proposed by Spectra Energy LP, which has sparked a debate across New England. But there are several other examples of pipelines with similar structures proposed across the country, from New Jersey to North Carolina. Fortunately, there are some steps regulators can take to minimize the risk of green-lighting unnecessary, expensive natural gas pipelines, namely providing heightened review procedures to affiliate-backed contracts.

Who’s Paying Whom?

Ordinarily, regulators insist on hard evidence that there’s a need for new capacity before signing off on a multi-billion-dollar pipeline. To build an interstate pipeline, developers need blessings from regulators, including FERC. One important key is having long-term contracts with customers for the gas – typically local gas and electric utilities, sometimes large industrial users or producers.

Signed contracts show FERC that there’s sufficient demand to support the huge investment. Or at least, that’s the idea. Things are fine so long as contracts between pipeline companies and utilities reflect arms’ length deals between parties with no corporate relationship. But when that’s not the case, things get thorny fast. Suddenly, you can end up with the same companies (or their affiliates) on both sides of a pipeline deal, effectively shaking hands with themselves. That creates a big incentive to get the deal done out of mutual financial interest, regardless of actual need.

In a normal business, lenders or shareholders are on the hook for bad bets, but not here. That’s because as state-regulated monopolies, local utilities have a legally guaranteed right to recover costs of providing service to their ratepayers. These costs include the signed contracts used to support the initial pipeline investment. This means developers get paid whether or not demand for gas shipped through their pipeline ever materializes. The only ones left holding the bag are the utility’s customers.

Too Close for Comfort

As the energy industry has evolved in recent years, local utilities are increasingly likely to exist as part of a larger corporate group, under an umbrella parent or holding company. Some of these subsidiaries fall outside the regulatory realm where local distribution companies exist, and thus play by very different rules. The concern is that a franchised public utility and an affiliate may be able to transact in ways that transfer benefits from the captive customers of the public utility to the affiliate and its private shareholders – and offload financial risk in the other direction. If there was a legitimate and pressing need to take service from the project, presumably the regulated utilities would already have signed up. Instead, we see a pattern emerge where affiliates become owners of the pipeline while simultaneously committing their franchise public utilities to fund the costs of the pipeline.

Policing Perverse Incentives

This new financial model has been popping up throughout the country, including the PennEast Pipeline, Mountain Valley Pipeline, and the proposed Access Northeast Project. Regulators need to be on the lookout for these kinds of troubling affiliate relationships.

Some states, including North Carolina, have laws requiring state utility commission approval of affiliate contracts. But in most places, the normal course of business is for state commissions to approve them, if they even do review the contracts in the first place. To address this regulatory gap, EDF recently requested the New York State Public Service Commission to take a harder look at these types of transactions.

At the federal level, FERC is supposed to approve pipelines only where there is a demonstrated need. But as the New Jersey Division of Rate Counsel pointed out in a recent FERC proceeding regarding the PennEast pipeline, when the project is supported by affiliate-backed contracts: “two-thirds of the demand for the pipeline exists because the Project’s stakeholders have said it is needed.”

Long-Term Consequences

The new corporate paradigms at work in the pipeline business result in a major shift of risk, where ratepayers end up shouldering the costs of long-term agreements, while the shareholders of the pipeline developers enjoy higher-than-average returns. Dr. Steve Isser recently highlighted the dangers of this risk-shifting in a recent paper, noting that it could lead to pipeline overbuild.

It’s time that FERC and state regulators apply heightened levels of scrutiny to these affiliate precedent agreements to ensure there is sufficient market need for new pipelines. If unaffiliated shippers are unwilling to sign these long term contracts, regulators also needs to ask: why should affiliated ratepayers?

Image source: EIA.gov