Study Reveals Vast Unrecorded Oil and Gas Industry Methane Emissions

A new study published today reveals that facilities that collect and gather natural gas from well sites across the United States emit about one hundred billion cubic feet of natural gas a year, roughly eight times the previous estimates by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for the segment. The wasted gas identified in the study is worth about $300 million, and packs the same 20-year climate impact as 37 coal-fired power plants.

A new study published today reveals that facilities that collect and gather natural gas from well sites across the United States emit about one hundred billion cubic feet of natural gas a year, roughly eight times the previous estimates by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for the segment. The wasted gas identified in the study is worth about $300 million, and packs the same 20-year climate impact as 37 coal-fired power plants.

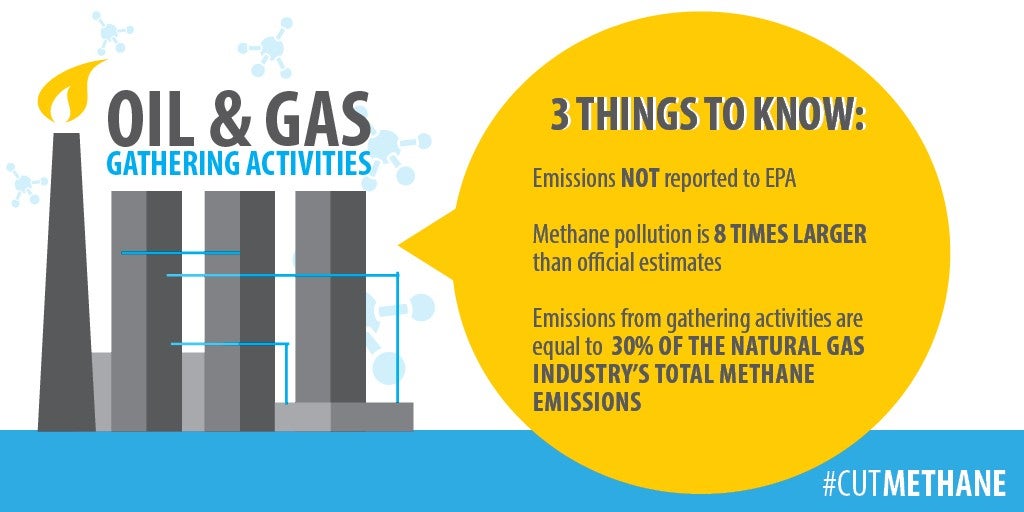

Until now, emissions from thousands of gathering facilities – which consolidate gas from multiple wells in an area and feed it into processing plants or pipelines – have been largely uncounted in federal statistics, yet they may be the largest methane source in the oil and gas supply chain. Indeed, the newly identified emissions from gathering facilities would increase total emissions from the natural gas supply chain in EPA’s current Greenhouse Gas Inventory by approximately 25 percent if added to the tally.

The study was conducted by scientists at Colorado State University and published today in Environmental Science & Technology.

EPA doesn’t track emissions from gathering facilities separately from production activities, and there have been no estimates and almost no research on them until now. One reason prior emissions estimates are so uncertain is because the number of facilities was completely unknown. Without conducting a full census, the CSU researchers were able to put the figure at between 3,846 and 5,470 facilities – a wide range, but far better than the guesswork than existed previously.

A different study in the Barnett Shale recently found over 250 gathering facilities, many more than anyone realized, and confirmed they were the industry’s biggest methane source in the region.

Compare & Contrast

The new CSU study also looked at natural gas processing facilities. Unlike gathering, the processing phase is well accounted for, in part because of stronger reporting requirements and regulatory oversight. Thanks to rigorous leak detection and repair programs, these processing emissions are much better controlled.

In fact, according to the study, processing emissions are lower than the EPA inventory (although they are also three times higher than reported under the EPA Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program, because of differing reporting requirements), enough to lower the inventory by about 5 percent.

That’s good news, but it’s nowhere near enough to offset the huge emissions uncovered on the gathering side. The combined result of the study still shows a net increase of 18.1%, a huge jump if it were accurately reflected in EPA figures for all natural gas systems. What’s more, the combined emissions from gathering and processing emissions are a whopping 87% higher than EPA inventory estimates for those sectors (which are currently tallied together as one).

Fixing the Problem

As EPA and the federal Bureau of Land Management prepare to introduce rules to reduce methane emissions from the oil and gas industry, these contrasting results underscore just how important effective policy can be.

EPA is already beginning to take some steps to address the issues uncovered by this research — there is currently a pending rule at the agency that would require gathering systems to report methane emissions to the EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program (which is separate from their estimated inventories), and this new study can help inform those changes.

But even more importantly, it is critical for EPA to propose methane emissions rules this summer that provide rigorous and comprehensive oversight of the oil and gas supply chain. As this new research shows, when operations go unmeasured, overlooked and poorly regulated, it can lead to massive leaks and little understanding of how to fix them.

Growing Body of Research

The study is the last of four EDF-led studies focused on the individual segments of the natural gas supply chain (production, gathering and processing, transmission and storage, and local distribution). A forthcoming synthesis paper will put these pieces together with 11 other studies to present a more complete picture of the methane emissions across the different sectors in the natural gas supply chain.