Hydraulic Fracturing and the EPA Water Study: Where Do We Go from Here?

It’s been two months since EPA released its much anticipated draft report on hydraulic fracturing, and organizations like ours are busy preparing their official comments, which are due at the end of August.

It’s been two months since EPA released its much anticipated draft report on hydraulic fracturing, and organizations like ours are busy preparing their official comments, which are due at the end of August.

But based on what we have learned so far and what has been written in the media, it’s important to spend some time on what the report said – and didn’t say – and what it all means.

“Is Fracking Safe?”

Scouring the EPA report for statements proving or disproving that hydraulic fracturing is safe will surely reveal both. It is true that water supplies have been contaminated by activities related to hydraulic fracturing. It is also true that the number of documented contamination events make up a small percentage of all wells. But “Is it safe?” is a red herring.

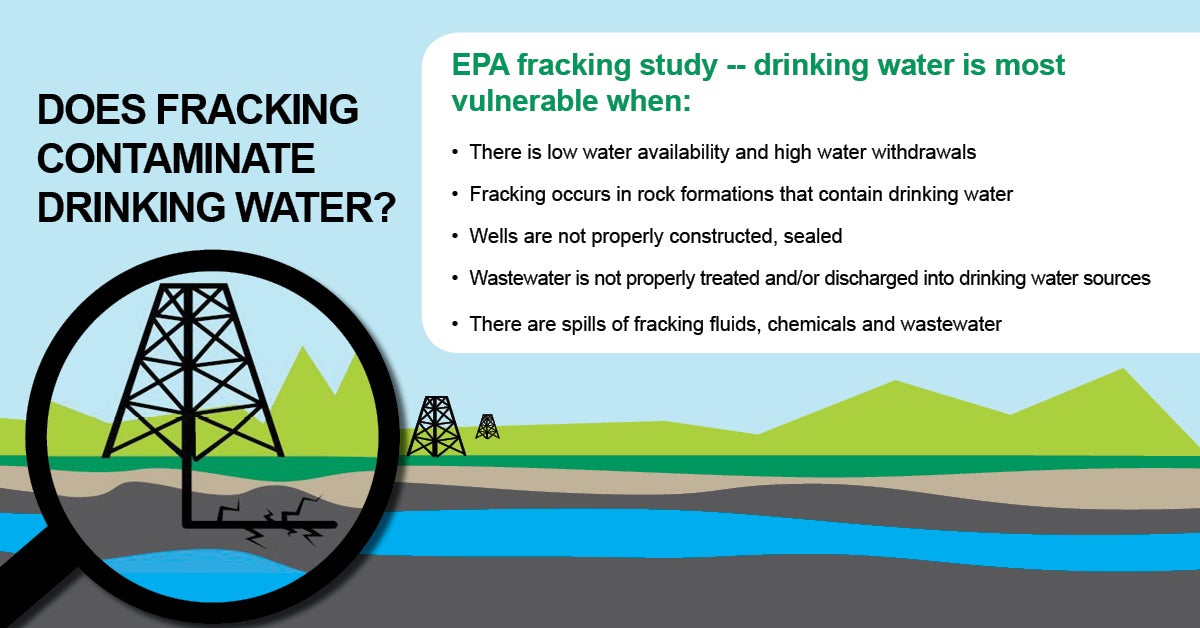

There are real, significant, and indisputable risks to land, water, and communities across the entire hydraulic fracturing “water cycle” – from water acquisition to waste disposal. EPA listed a number of them. Those risks can be considerably reduced with smart policies, technologies, procedures, and monitoring. Does the current evidence show that these risks have been reduced such that we can call the practice “safe” from start to finish? The report leads us to one conclusion: there isn’t enough evidence yet to make that call.

Perhaps the most quoted line from the nearly 1,000-page report states that EPA “did not find evidence that [fracking] mechanisms have led to widespread, systemic impacts on drinking water resources.”

To clarify, the lack of “widespread, systemic impacts” simply means that hydraulic fracturing activities aren’t currently impacting water supplies everywhere, not that they can’t impact the water supply anywhere. Where impacts do occur – and EPA confirmed a number of them – they can be devastating to local communities and the environment.

EPA’s report validated a number of EDF’s existing concerns. Sloppy oil-and-gas-field procedures, accidents, and often the lack of basic regulations that keep pace with practices, technologies, and science mean contamination can and does happen. Poor monitoring and insufficient data mean we can’t always know if and where contamination occurs. Even where we can pinpoint a problem, we often don’t have the data or analytical capability to know how bad it is or what we need to do about it.

What Remains Unknown

EPA’s draft report is, for the most part, a review of existing studies; little new research or fieldwork was conducted. And the universe of existing research is sparse in many areas. In the executive summary, EPA states “data limitations preclude a determination of the frequency of impacts with any certainty.” In other words, EPA can’t say for sure how bad things are because it doesn’t know. No one does.

This glaring disclaimer is perhaps the most important takeaway from the report, and it’s echoed numerous times throughout. EPA highlighted caveat upon caveat and uncertainty upon uncertainty, recognizing its limited ability to fully assess potential impacts to drinking water, such as:

- Future cumulative water use and local impacts

- Types and volumes of chemicals spilled, spill causes, containment and mitigation measures, and sources of spills

- Whether fluids and gas move in unintended ways below ground

- Evaluation of the design and performance of individual wells or wells in a region, particularly in the context of local geology or presence of other wells

- The ability to tie possible impacts to specific well construction, operation, or maintenance practices

- Total number of spills, released volumes and associated concentrations

- National picture of wastewater generation and management practices

- Analysis of influent and effluent from facilities that treat wastewater

- Toxicity and potential impacts for single chemicals as well as mixtures of chemicals

Furthermore, a number of potential areas of impact were simply beyond the scope of EPA’s review:

- Aspects of the environment other than the water cycle (seismicity, air quality, ecosystems)

- Site selection, well pad, and infrastructure development (like roads and pipelines)

- Well closure and site reclamation

- Impacts on other water users (like farmers)

- Worker health and safety

- Transportation-related spills, drilling mud spills, spills that occur off-site (such as during transportation or storage of chemicals in staging areas), and spills associated with wastewater disposal in underground injection control wells.

With this many unknowns, it’s simply impossible to make any definitive conclusions about the hydraulic fracturing activities reviewed by EPA other than “we need to know more.”

Above all else, EPA’s report is a clarion call for more research, while also using what we know now about vulnerabilities to spur improvements in regulations and industry practices. Instead of trying to reach consensus or draw conclusions from an incomplete assessment, we need to start talking about how we can fill some of these gaps, minimize risks, and address vulnerabilities.

Addressing Major Vulnerabilities

Addressing Major Vulnerabilities

EPA highlighted key vulnerabilities to water sources so industry, regulators, and the public can better understand and address them. EDF is also independently engaged to advance this work – our strategy overlaps with a number of EPA’s indicated areas of vulnerability, including: well integrity, spills, and wastewater.

Well Failure

As we have long known, EPA concluded that poorly designed or constructed wells can allow fluids and gasses to move out of wellbores and impact water resources. With smart polices that require careful planning, constructing, testing, and monitoring of wells, these failures can be minimized, if not eliminated. For example, Texas updated requirements for drilling, casing, cementing, and fracture stimulation in 2013 – incorporating new technology and leading practices. In the year after the rule became effective, blowout incidents were cut 40 percent, proving that smart policies can directly reduce risks to water sources as well as to worker safety. It’s why EDF is working to get more states to adopt similar progressive policies.

Spills

In addition to well integrity failures, a large majority of ground and surface water impacts are due to surface releases of chemicals, fracking fluids, and wastewater – like a recent pipeline rupture in North Dakota that resulted in more than 3 million gallons of salty produced water spilling into a nearby stream. We know very little about the broader impact of such spills due to a lack of data on spill numbers and volumes (EPA could only estimate spill frequencies for two states), as well as unknown characteristics of the fluids spilled. More than 1,000 chemicals are used in hydraulic fracturing or returned in wastewater. But in EPA’s limited hazard assessment, key chronic toxicity information was lacking for 87 percent of chemicals identified as associated with hydraulic fracturing. EDF believes the frequency and impact of these spills can be dramatically reduced, but it will require improvements in the way chemicals, frac fluids, and wastewater are reported, stored, transported, and otherwise handled on and off-site.

Wastewater Disposal

The oil and gas industry produces more than 800 billion gallons of wastewater every year, and our knowledge of its content, toxicity, and treatability is severely limited. This is especially important given a potential trend toward permitted treatment and disposal of this waste into streams or onto land. EPA concluded that there was limited information regarding the influents and effluents from facilities that treat wastewater from hydraulic fracturing operations and that improved analysis methods are needed so we can better determine concentrations of chemicals like organics and radionuclides.

EDF is working to fill those data gaps by launching studies to improve our ability to analyze and effectively treat oil and gas wastewater. Because new treatment and recycling efforts often are being pursued in the name of water conservation, EDF is working to ensure that these practices do not create more environmental risks than they solve.

Looking Ahead

EPA has provided a comprehensive, authoritative snapshot of what we know and what we don’t about the interplay between hydraulic fracturing activities and water. It is an important but incomplete assessment that, unfortunately, poses more questions than it answers.

More broadly, the report has affirmed the need for a widespread, data-based approach such as the one EDF has taken on this and other issues:

- Get the science right – the data shortcomings highlighted by EPA have sharpened our focus on various scientific areas where our staff can contribute, as we have done with methane emission science.

- Get the rules right – the report underscores the need for a process of continuous improvement, building on growing knowledge and changing technologies to better design and implement existing and emerging industry practices and regulations that can minimize risks to our water resources.

So, where do we go from here? Until we can fill the data gaps revealed by EPA’s water study, we can’t be certain that existing rules and industry practices adequately ensure that hydraulic fracturing and its associated activities are done “safely.” But that doesn’t mean significant progress can’t be made today to reduce risk and address known vulnerabilities with smart policies, like the 2013 work in Texas that cut the incidence of well blowouts nearly in half. EPA’s water study is an important part of the ongoing debate but clearly continued focus on the steps we can take now to protect oil and gas communities from localized impacts, even while we gather more data to further minimize risks, is essential.

Image Sources: Wikipedia, EDF