In South America’s Humboldt Current, this collaboration to build more climate-resilient fisheries brings together two great fishing nations

By Kristin M. Kleisner and Mauricio Galvez

By Kristin M. Kleisner and Mauricio Galvez

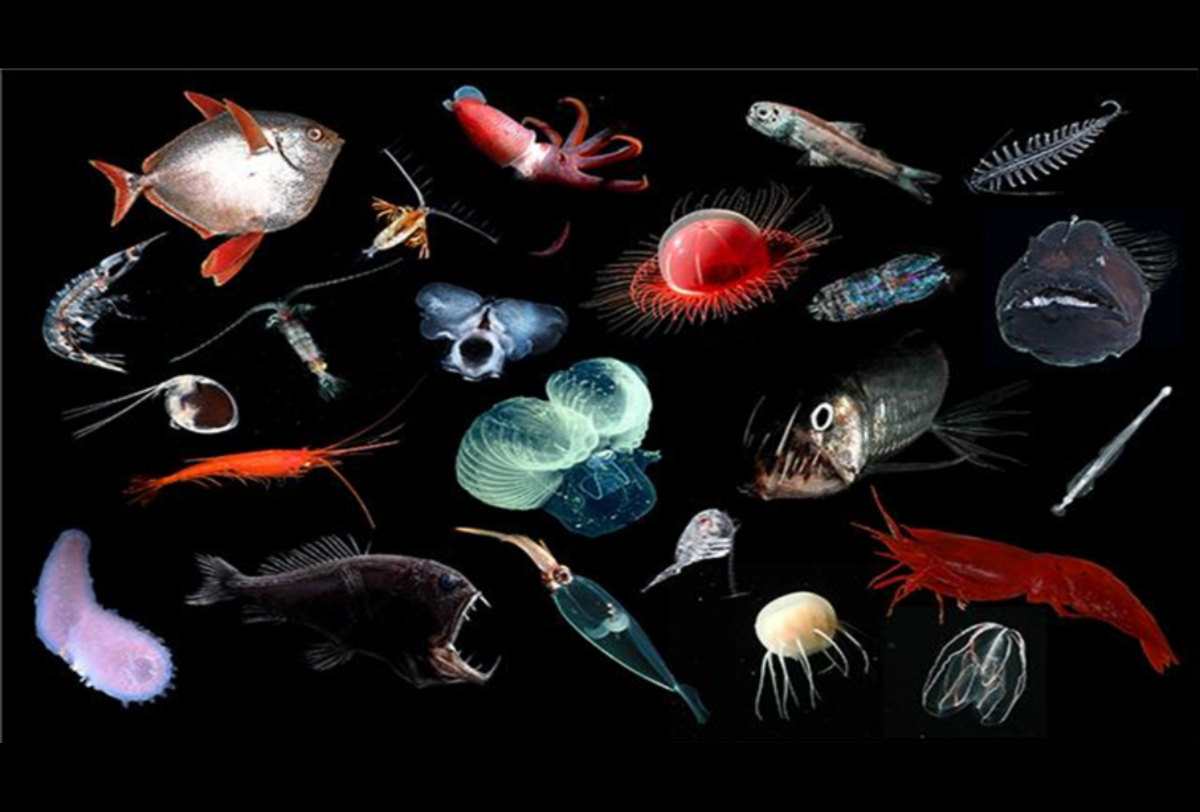

Along the Pacific coast of South America, a powerful ocean current brings to life one of the most abundant and productive ecosystems on the planet. The Humboldt Current System spans from southern Chile to Ecuador, pulling cold, nutrient-rich water from the ocean depths to the surface. This upwelling, as it’s called, creates the conditions that feed tiny plankton that form the basis of a vast food web, attracting small fish such as anchovy and mackerel, and larger predators like tuna, squid and sharks. This food chain is not only important for sustaining the marine ecosystem, but also provides food security for millions of people whose livelihoods depend on the fisheries of the Humboldt Current. As such, the Humboldt Current System also sustains as much as 20% of the world’s wild-caught fisheries production.

In recent years, fishers and scientists have seen climate change add to the complexity and variability of the Humboldt Current System. Natural variations in ocean conditions change upwelling intensity and frequency from year to year, as local fishers can attest. Scientists refer to these conditions as El Niño (warm) or La Niña (cool) events, which have a strong effect on how many plankton there are, and whether they are close to shore or further out to sea. Several studies suggest upwelling intensity will shift poleward. If this happens, upwelling may become less intense off the Peruvian coast and more intense in Chilean waters. This change would ripple through the food web, shifting the distribution of commercially important fish such as anchoveta, and creating additional challenges for fishery managers.

EDF is excited to continue working with experts from Chile and Peru to help make this vision of a comprehensive system for observing, prediction and early warning a reality in the years to come.

To explain how we are doing this, allow us to get a little wonky here!

Understanding oceanic changes first necessitates a system of coastal and ocean observing, or a “COOS,” that operates at a scale that can pick up ecosystem-level changes and shifts in species’ distribution and abundance. This is especially true for fish and other ocean species that cross international borders. Many countries operate some type of COOS using observations from various mobile technologies — things like ship-based surveys, autonomous ocean gliders, drifters — and stationary technologies like radars, profiling floats and coastal moorings. In an ecosystem like the Humboldt Current, where physical and biogeochemical processes occur at various temporal and spatial scales, having a mix of mobile and stationary observing technologies that operate across international borders is key.

Having access to this type of information will allow each country to improve adaptive and forward-looking fisheries management in a complementary manner.

This enhanced technical capacity will improve the ability of scientists to understand the ecosystem-level, climate-related effects on fisheries, and, based on this understanding, develop prediction and early warning indicators of climate impacts on fisheries to help managers adequately respond to changes proactively. Having access to this type of information will allow each country to improve adaptive and forward-looking fisheries management in a complementary manner.

Overall, this international, multidisciplinary project will bolster collaboration between two great fishing nations, which are now motivated to proactively address and plan for climate-related effects in their ecosystem. EDF is excited to continue working with experts from Chile and Peru to help make this vision of a comprehensive system for observing, prediction and early warning a reality in the years to come.