Catch Shares: Harvesting Sustainable Catches

Originally published on November 18, 2013 on the Oceans Health Index Website

Introduction

Written by Steven Katona, Managing Director, Ocean Health Index

Maximizing sustainable food production from the ocean by harvest of wild fish stocks and production of farmed species by mariculture is one of the 10 goals evaluated by the Ocean Health Index, and it is especially closely watched because it is so critical for the future.

Three billion people out of today’s world population of 7.1 billion people depend on seafood for their daily protein and fish contribute a greater proportion of protein to the average diet than poultry. A single serving of fish or shellfish (150 g) provides 60% of a person’s daily protein requirement, but the ocean’s continued ability to meet that need is in doubt. Our population is rising steadily and will reach about 8 billion by 2024 and 9 billion by 2040, but the annual catch from wild ocean fisheries has stayed at about 80 million metric tons since about 1990 despite increased effort. The reason is that too many stocks are overfished and too much productivity is sacrificed as bycatch, illegal and unregulated catch and as a result of habitat loss caused by destructive fishing practices.

Yet without increased wild harvest and augmented mariculture production, the risk of malnutrition will increase for hundreds of millions of people, because the catch will have to be shared by so many more mouths.

Why would we expect fish landings to increase in the future if they haven’t done so since 1990? Clearly with business as usual, they won’t, but a number of new strategies and tools offer hope. Catch shares is one of them. We’re pleased to welcome Kate Bonzon, Director of Environmental Defenses Fund’s Catch Share Design Center, to explain how catch shares are working worldwide and highlight some of their benefits.

Even though catch shares have been used in a diversity of fisheries around the world, the idea of catch shares is new in many places, and it has occasioned some misunderstanding and subsequent debate around the best way to manage fisheries. However, catch shares give a powerful incentive and opportunity for fishers to care for their fish stocks, thereby improving the consistency, sustainability and possibly magnitude of their catches, while also improving their livelihoods.

More sustainable fishing will not only help fishers and fish stocks, but it will also improve scores on many of the other goals evaluated by the Ocean Health Index. Of course there are trade-offs between the goals, but meeting the goals for sustainability embodied within each goal will improve the ocean’s ability to sustainably deliver a range of benefits to people now and in the future. What’s more, the ocean’s animals, plants and habitats will benefit too.

Catch Shares: Harvesting Sustainable Catches

Fish were once thought to be so abundant that we could take our fill and never deplete them; that wild fisheries were inexhaustible and would always be plentiful. But over the past few decades, there is growing recognition that most of the world’s wild fisheries are in trouble and fishing has had a tremendous impact. Globally, nearly two-thirds of wild fisheries are overfished, leaving depleted fish stocks and low yields. New evidence on fisheries with little data, which account for 80% of the global catch, is especially concerning. Once thought to be relatively stable, many of these fisheries are, in fact, overfished and facing collapse. Depletion of this resource threatens not only ocean health but the billions of people who depend on fish for food and jobs.

The good news is fisheries are a renewable resource. And the key to sustainably managing them is ensuring there are enough fish left in the ocean to produce future generations. Future fish generations will keep fresh and sustainable seafood on the plates of the billions of people around the world who rely on them for protein, and wages in the pockets of millions of fishing industry workers who depend on them to support their livelihoods.

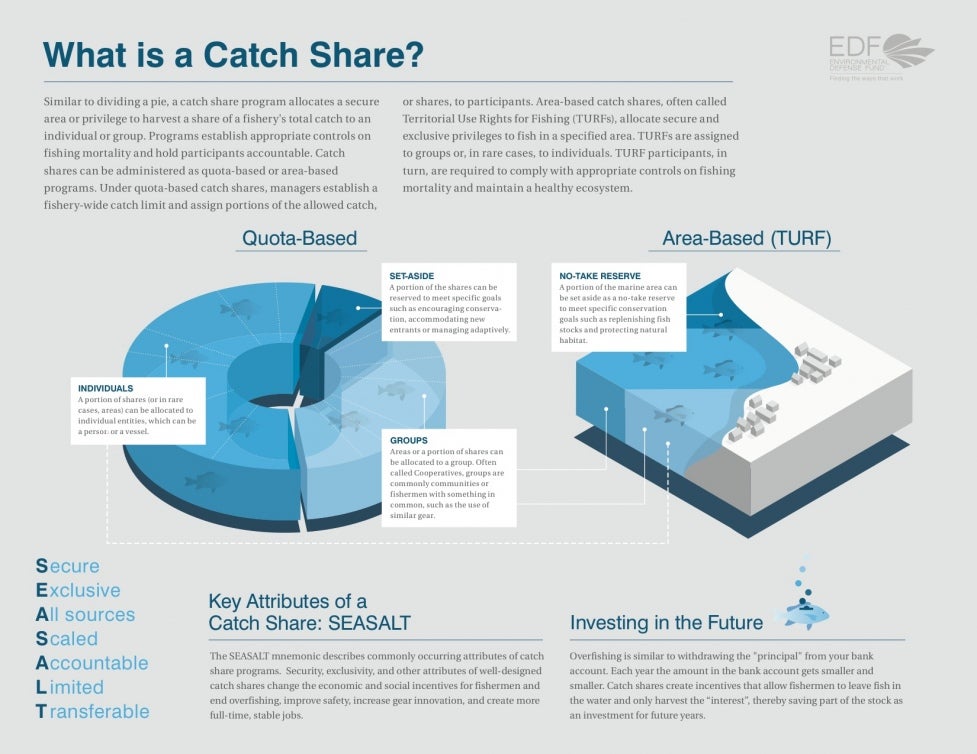

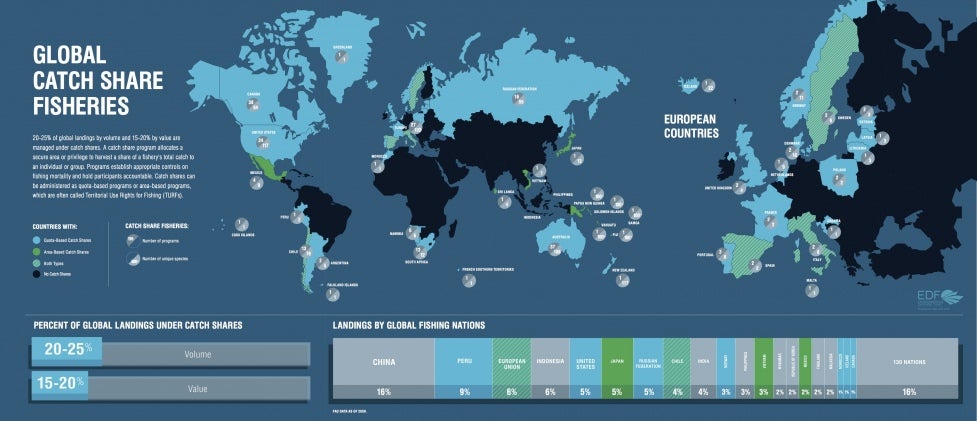

And there is more good news. There are effective fishery management programs-called catch shares-that are doing all of the above. As of 2013, about 200 catch shares programs are managing more than 500 different species in 40 countries. Very much like dividing a pizza or pie, catch shares give a secure fishing area or privilege to catch a share of a fishery’s total allowable catch to an individual or group. And with this privilege, fishing participants are expected to fish within their allotted amount.

The success of catch shares lies in the ability to give fishermen a long-term stake in the fishery and tie their current behavior to future environmental outcomes. Specifically, catch shares align fishermen’s incentives through a system of rights, responsibilities and rewards. By giving fishermen the privilege or right to a secure area or share of the catch, fishermen also retain the responsibility to conserve fish stocks and marine ecosystems and are subsequently rewarded by stable and healthy fish populations. Importantly, catch shares are flexible and can be custom designed to meet the different characteristics and goals of diverse fisheries. Some catch share programs have allocated shares to groups—often called Cooperative catch shares—and others have allocated shares to individuals—often called Individual Fishing Quotas (IFQs) or Individual Transferable Quotas (ITQs). Area-based catch shares, often called Territorial Use Rights for Fishing, or TURFs, allocate secure, exclusive areas to fishermen. And within these differing types of catch shares are a multitude of design features that have, and can, be used to meet different goals. Around the world, from small artisanal fisheries to large commercial fishing operations, well-designed catch share programs are increasing compliance with catch limits, reducing the amount of bycatch and discarded fish, increasing revenues and reducing fishing expenses, proving that good yields can indeed happen sustainably. A 2011 study of 345 fish stocks around the world found that those managed with catch shares had significantly lower cases of overexploitation when compared to conventional management practices. And another study found that the implementation of these systems “halts, and even reverses—widespread fishery collapse.” This positive trend is largely driven by catch shares ability to encourage compliance with mortality controls.

Numerous studies on these fisheries have reported a dramatic drop in bycatch and discarded fish including a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) report which found that catch share fishermen in the Gulf of Mexico reduced red snapper discards by 50% in 2010, just three years after a catch share program was implemented. And in some fisheries like the Alaskan pollock fishery, fishermen create voluntary no-take zones to avoid bycatch of at-risk species while targeting specific species. In the Alaska halibut fishery after just one year of catch share implementation, there was an 80% drop in ghost fishing (when lost or abandoned gear continues to kill fish).

Many of these fisheries used catch shares to meet their own specific goals, such as economic self-sufficiency. In Samoa, the culture and livelihood of many native communities relies on the practice of fishing. In fact, in the Safata District of Samoa, a settlement of nine villages on the remote southern coast of Upolu, the community is highly dependent on fisheries as a source of food and income. Approximately 88% of households engage in fishing activities and the community derives about 77% of its entire food source from adjacent lagoons and reefs.

For centuries, village chiefs successfully managed coastal fishing areas through secure and exclusive tenure over defined fishing areas in a practice known as “matai.” After colonization took place in the 1800s, these chiefs and their native communities lost ownership of their seas. In the mid-1980s, the island’s inshore fisheries were at risk due to overexploitation of stocks and destructive fishing practices.

The Samoan government worked with the native fishing communities to help them develop village-based management programs. The Safata District was able to develop a district-wide TURF in 2000, which created bylaws to manage community members’ fishing efforts and limited outsiders’ access to their fishing area. And this has all proved to be fruitful. After development and implementation of the TURF, food fish and other important species have increased in abundance and the district is now known as one of the largest and most successful community-managed areas in Samoa. The community’s catch share, Samoan Safata District Customary User Rights Program, has resulted in strong community support, high compliance with regulations and the community’s members are reporting increased catches despite spending less time fishing.

In Japan, fishing Cooperatives coordinate within and across TURFs to improve fishery sustainability and promote economic efficiency. Since the early 1700s, local Japanese fishermen formed to protect their nearshore marine resources. However in the 1930s, when coastal fishing boats became motorized, fishing pressure increased and become more difficult to regulate. Overfishing and conflicts among fishermen began to occur, primarily between coastal fishermen and industrial trawlers. The Japanese government addressed this by formalizing the rights and co-management responsibilities of local cooperatives as part of the Fishery Law of 1949. Almost 65 years later, the Japanese Common Fishing Rights System has enhanced coastal fishery management. Fishermen work together within their Cooperative to effectively manage their share of the resource and they work across Cooperatives to ensure good management of resources that straddle multiple communities. The program established a system of nested governance that provides fishermen with a voice in the management process. And importantly, the program allows Cooperatives to ensure compliance with catch limits that support the health and sustainability of their fisheries.

These are just two success stories of many instances where catch shares are helping to achieve the food provision goals of fisheries. And at Environmental Defense Fund (EDF) we are working to ensure that fisheries stakeholders have access to the knowledge and tools needed to implement sustainable fishery management programs that allow them to achieve all of their goals, whether they are environmental, social or economic.

We recently released a comprehensive toolkit for designing and implementing such systems. The toolkit provides fishermen and fishery managers with many low-cost and highly replicable solutions to management issues, including a guide on science-based management of data-limited fisheries. It expands upon our original Catch Share Design Manual released in 2010 and includes feedback and guidance from more than 80 global experts.

The toolkit can be found at fisherytoolkit.edf.org, and consists of:

- An updated Catch Share Design Manual that guides fishermen and fishery managers through a step-by-step process to design catch shares

- A dedicated volume on designing Cooperative Catch Shares, which includes in-depth guidance on effective co-management of fisheries

- A dedicated volume on designing Territorial Use Rights for Fishing (TURFs), including new concepts for addressing the unique challenges of nearshore fisheries

- Guides on science-based management for fisheries that have limited data and transferable effort share programs, a form of rights-based management that has served as a stepping stone towards more effective, long-term management solutions

- More than a dozen in-depth reports on fisheries, from Samoa to Spain, that have customized catch shares to meet their goals

- A searchable database of global catch share fisheries, accessed through an interactive map

- “What’s the Catch?,” an online game that allows players to captain their own vessel and experience the ups and downs of commercial fishing

We hope that by providing fishing communities worldwide with these tools, we can better equip them to sustainably manage their fish stocks and keep our oceans healthy for many generations to come.