What Happened:

What Happened:

Bipartisan support is growing for food safety reform as U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is considering comments on a new process for reassessing chemicals already on the market . On January 21, EDF submitted comments to FDA on how the agency should strengthen its proposal for a process to ensure the safety of existing ingredients in the market. While EDF supports modernizing FDA’s Human Food Program processes and methods, the current proposal falls short on transparency, efficiency, and scientific rigor.

Why it Matters:

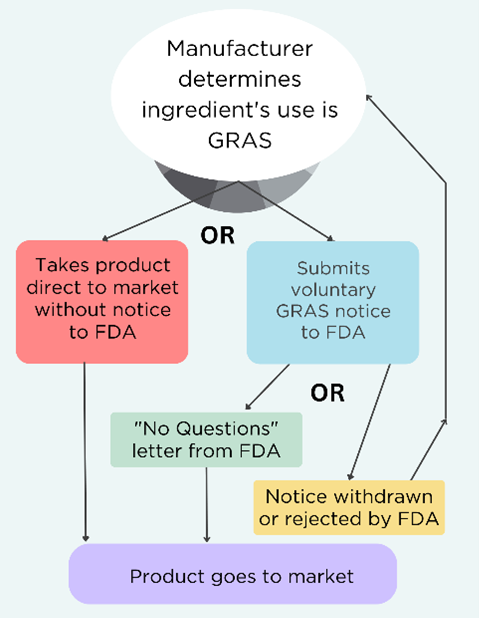

The public deserves a systematic, science-based approach to food chemical safety. FDA’s current process is outdated, opaque, and reactive rather than proactive. Delays in addressing chemical safety are common, with FDA often taking years to act on food additive petitions and chemical reassessments. Many food chemicals were approved decades ago using little or no data and have not been reevaluated since.

FDA often relies only on its own studies, while ignoring or disregarding findings from other authoritative institutions such as the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), seemingly unable to acknowledge modernizing science. This failure to consider the full picture and the best available science undermines public health.

Additionally, the agency fails to consider the cumulative effects of multiple related substances. People aren’t exposed to single chemicals in isolation, yet the FDA continues to evaluate them as if they are.

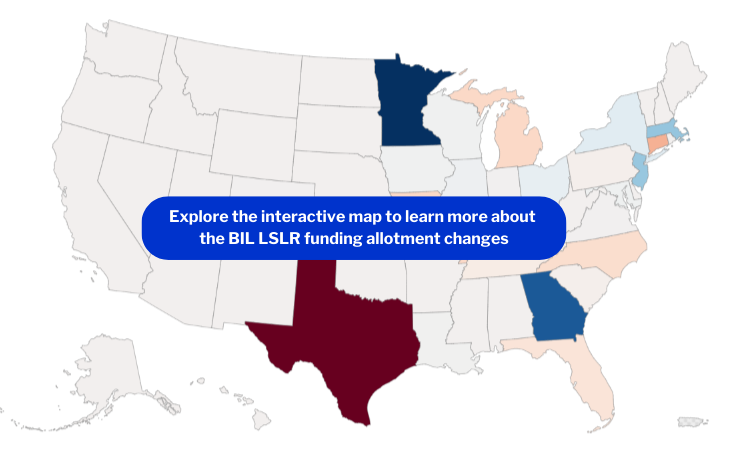

While FDA leadership has emphasized that food chemical safety is a top priority for the Human Foods Program, historical lack of action has driven states like California to implement its own food additive regulations. This state-by-state approach creates a patchwork of rules that highlights the urgency for stronger federal leadership to protect all Americans from toxic chemicals.

Our Take:

FDA’s proposed process is a step forward but needs significant improvements.

- FDA should set up a true prioritization process

- FDA’s proposed process doesn’t identify which of the 10,000+ chemicals authorized to be used in food will be reassessed or why. FDA needs to outline specific criteria for prioritizing chemicals (e.g., risks to children’s health, endocrine disruption, biomonitoring data); start with high-priority chemicals identified by authoritative bodies like U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) and the National Toxicology (NTP) Program; and make the process transparent by publishing rankings and methodology. Other agencies such as EPA have done this; FDA could build on their successful approaches.

- Commit to comprehensive assessments

- FDA proposes using “focused assessments” based on limited data, skipping peer review and public transparency. FDA should commit to comprehensive assessments that use all available evidence and limit focused assessments to when immediate action is needed.

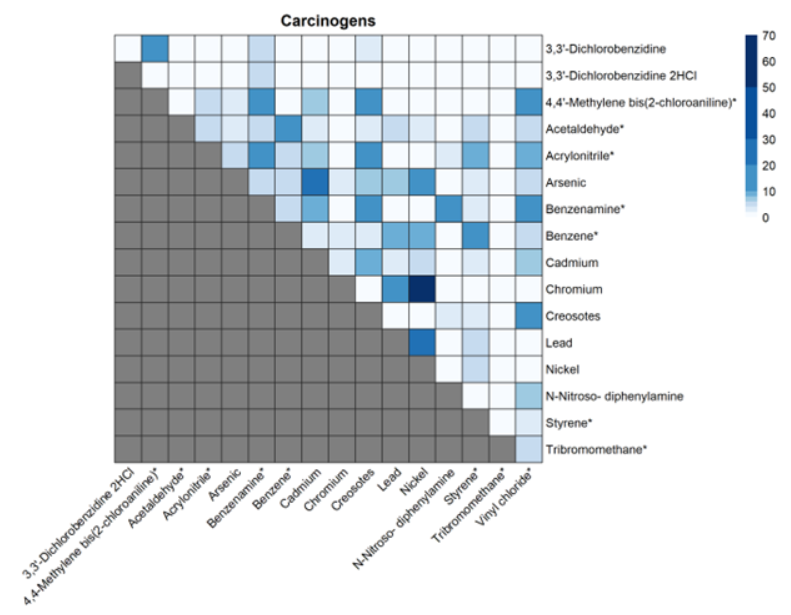

- Enforce the Delaney Clause

- FDA must prioritize removing carcinogens, as mandated by law, without redundant reassessments.

- Embed peer review and public input

- FDA should establish a scientific advisory committee, hold public comment periods, and ensure robust, external peer review for influential decisions.

- Separate risk assessment from risk management

- FDA should create an independent office to ensure unbiased chemical risk reassessments to avoid bias from teams that approve chemicals for market use.

- Consider cumulative effects

- FDA often assesses chemicals in isolation, ignoring how we are exposed to multiple chemicals at the same time in real life. FDA should evaluate combined chemicals exposures, as required by law.

While developing this process, FDA can take immediate action on priority chemicals. EDF and others have already petitioned the agency to act on harmful phthalates, per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), cancer-causing solvents (including methylene chloride), and titanium dioxide, BPA and lead. These toxic chemicals do not belong in our food. With growing bipartisan support for stronger food safety regulations, FDA has an obligation to be a leader in this space. About two-thirds of American adults across political ideologies “strongly or somewhat favor” restricting or reformulating processed foods to remove added sugars and dyes signifying wide support for greater regulation on food additives.

Next Steps:

It is critical that FDA reevaluates its processes for determining the safety of chemicals in our food. EDF will continue to pressure FDA to act now on high-priority food chemicals, using the best available science and enforcing laws that effectively protect people’s health.

Go Deeper:

Read the full version of the comments EDF submitted to FDA here.