A lot has changed since I first started working to reduce pollution from hog farms in North Carolina. That was back in the 1990s, during my early years at Environmental Defense Fund.

Back then, industry wasn’t exactly eager to sign on to new, environmentally-friendly technologies to manage hog waste. So it’s gratifying now to work with Smithfield Foods, the world’s largest pork producer, as it voluntarily commits to reduce its carbon footprint in a meaningful way.

Hog farms have long created both environmental and health problems for residents in the coastal plain of eastern North Carolina. Manure in the farms’ waste lagoons produces methane, ammonia, and other gases that contaminate both the air (causing respiratory problems as well as accelerating climate change) and the water (where nitrogen contributes to algae blooms, and at times, large-scale fish kills).

I collaborated with North Carolina State University for many years in evaluating possible technologies that can reduce pollution from pork production. This work led to 2007 legislation in North Carolina that banned new permits for lagoon and sprayfield hog manure treatment systems and established environmental performance standards for alternative treatment systems.

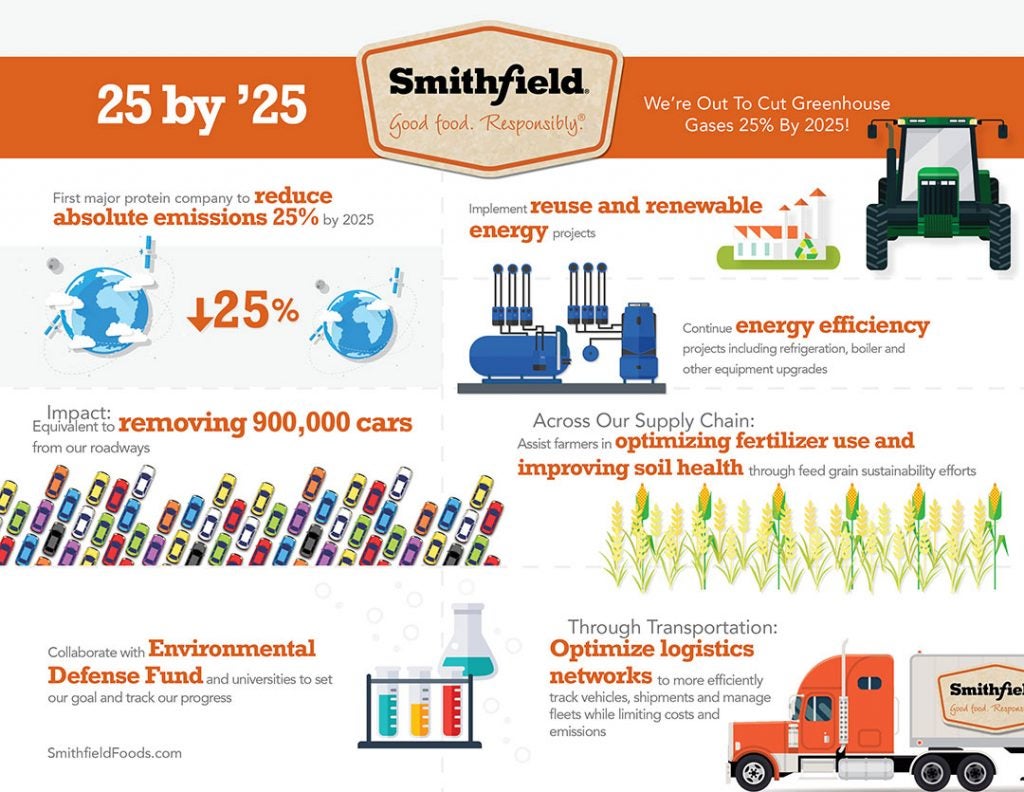

Now it’s 2016, and Smithfield has decided to take the lead in the animal protein industry by reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 25 percent by 2025. That’s more than 4 million metric tons, or the equivalent of removing 900,000 cars from the road. But in order to succeed, it first had to understand its baseline emissions footprint. That kind of assessment required a thorough lifecycle analysis — a careful look at emissions produced throughout the company’s supply chain, from raw materials to disposal to retail to in-home consumption.

Companies’ individual lifecycle assessments are critical to developing plans to reduce greenhouse gases. The quality of the data collected for the assessment determines how useful the results will be in planning the changes companies will undertake to meet their goals. Company-specific data illuminates individual emissions hotspots in supply chains — those critical points where companies can focus their energy and attention to reducing negative impacts most effectively.

Smithfield contracted with the University of Minnesota’s NorthStar Institute for Sustainable Enterprise to create a custom greenhouse emissions inventory for the company, and EDF agreed to review the analysis.

Let’s take a look at the two major greenhouse gas emissions hotspots the lifecycle analysis identified, and how Smithfield plans to reduce greenhouse gases:

- Pigs consume a great deal of corn (as well as soy) which requires a large amount of nitrogen and other nutrients often provided by industrially-produced fertilizer. When applied to the land, the nitrogen in the fertilizer results in the release of nitrous oxide from soils, which is a potent greenhouse gas. In fact, feed production accounts for about 20 percent of Smithfield’s greenhouse gas emissions. The solution? EDF is working with Smithfield to optimize its fertilizer use, so it can get the crop yield required to feed the pigs while minimizing the surplus nitrogen which fuels nitrous oxide emissions.

- The other dominant emission hotspot comes from manure management. In Smithfield’s case, this accounts for more than a third of its greenhouse emissions. Hog manure is typically flushed from the barn into an open earthen lagoon. Smithfield now plans to cover lagoons to reduce the methane that’s released into the air on 30 percent of its company-owned farms. Smithfield is also committing to help its contract growers do the same. Those lagoon covers will also prevent ammonia from being lost to the air — a huge benefit because atmospheric ammonia losses result in public health and environmental risks. By capturing ammonia under the lagoon covers, Smithfield can use it as fertilizer, offsetting some of the inorganic fertilizer the company otherwise would have to purchase.

While these commitments by Smithfield Foods will not solve all (or even a majority) of the public health and environmental impacts of hog farms, this is a meaningful step by the company. It is also promising that NorthStar’s work with Smithfield can be readily adapted to other companies to develop their own lifecycle analysis.

I’m encouraged that Smithfield is taking a leadership role in this endeavor, and proud of the roles that EDF has played. EDF will continue to work with Smithfield to make this commitment a reality, and to address the remaining issues associated with pork production.

It is my hope that the commitment by Smithfield Foods will encourage other livestock producers to step up and take the actions necessary to reduce the public health and environmental impacts of their operations.