Measuring the true impact of Colorado’s climate delay: Minding the emissions gap (Part 2)

After Colorado legislators passed landmark climate legislation in 2019, which included a statutory mandate directing the Air Quality Control Commission (AQCC) to adopt rules and regulations to reduce statewide emissions, the state has yet to even propose a policy framework capable of getting the job done. This three-part series explores the impact of Colorado’s delay, analyzing the impact on total emissions and the state’s ability to meet its own climate targets.

Editor’s note: This post was last updated Jan. 19. 2021 to reflect Colorado’s final greenhouse gas roadmap.

This year started with promising climate news in Colorado: The state’s largest electric utility, Xcel Energy, announced it will close two of its coal-fired units sooner than planned and support plant workers through retraining and retirement opportunities. While this is a step in the right direction for Colorado’s clean energy future, much more policy action will be needed to meet the state’s statutory emissions goals.

In Part 1 of this series, EDF analysis uncovered the cumulative impact of the Colorado Air Quality Control Commission’s (AQCC) inaction on greenhouse gas emission reductions. Delays will have profound consequences for the total pollution that the state emits over the next decade, which could mean more severe long-term climate damages for Colorado communities and ecosystems. The AQCC’s refusal to seriously evaluate policy mechanisms for much faster and deeper reductions flies in the face of what Colorado legislators mandated in 2019. They set a clear timeline for the AQCC to swiftly propose regulations and reduce statewide emissions 26% by 2025, 50% by 2030 and 90% by 2050, all relative to 2005 emissions.

In Part 2 of this series, we dive into a recent EDF report and analyses released by both the state and other researchers that reveal how Colorado is far off track from achieving these upcoming 2025 and 2030 statutory targets under current policies. The state’s glaring ‘emissions gaps’ underscore the need for transformative leadership on a policy framework capable of securing the reductions consistent with its goals — and protecting Coloradans for generations to come.

Measuring the gaps

It is worth repeating from Part 1 that near-term reductions in pollution matter enormously. Every decade, year, and day on our current trajectory—failing to make the needed reductions particularly in long-lived climate pollutants—will result in additional emissions building up in the atmosphere and more costly climate damages.

Colorado’s ability to meet its 2025 and 2030 goals will set the course – and determine the state’s climate future – for the latter half of the century. Unfortunately, a recent report from EDF analyzing progress across states with climate commitments found that Colorado is far off course from where it needs to be. Under current policy adopted through January 2021, and capturing Xcel Energy’s announcement to fully retire the Hayden Generating Station no later than the end of 2028, EDF’s analysis reveals the state is only expected to reduce emissions from 2005 levels by 7-16% in 2025 and 19-26% in 2030. In other words, Colorado faces an emissions gap of net 13-24 MMT CO2e in 2025 and net 31-40 MMT CO2e in 2030, depending on how quickly emissions rebound from the pandemic.

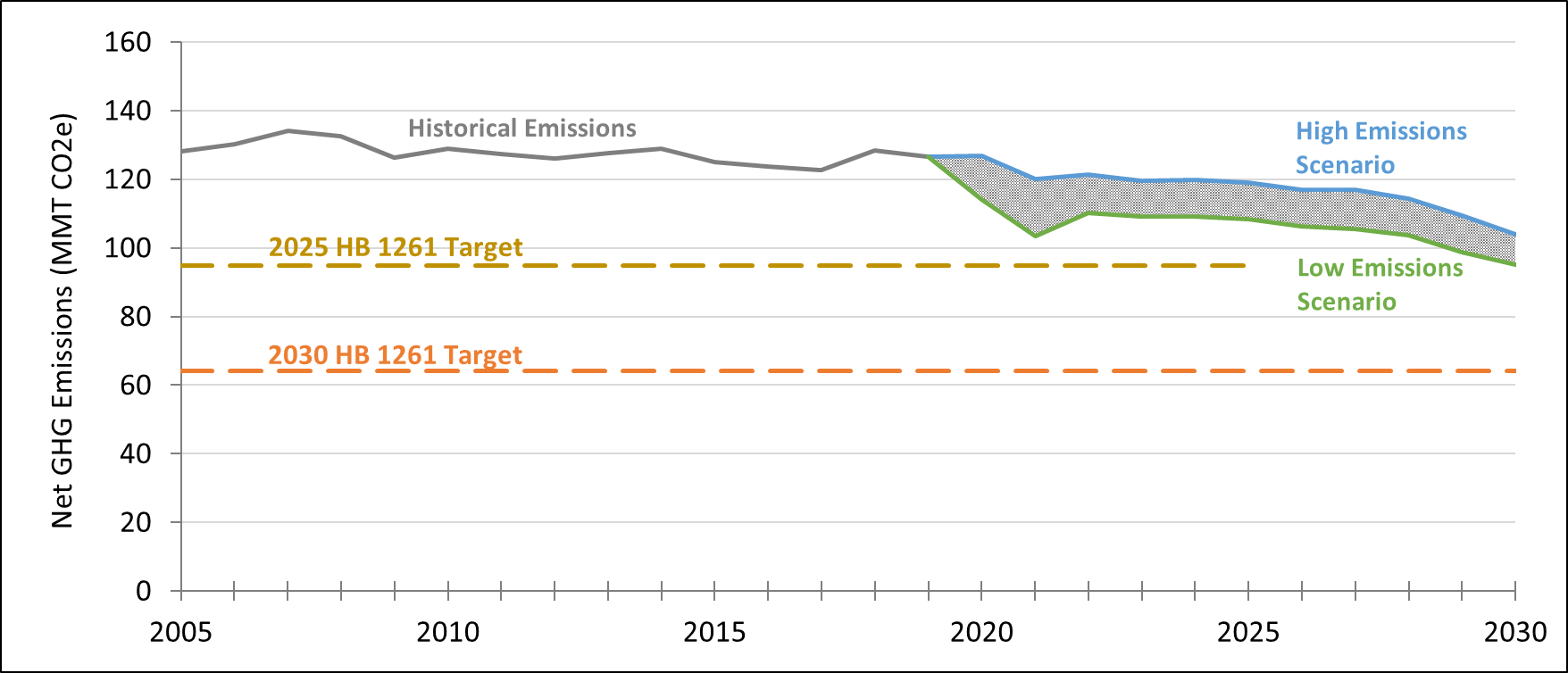

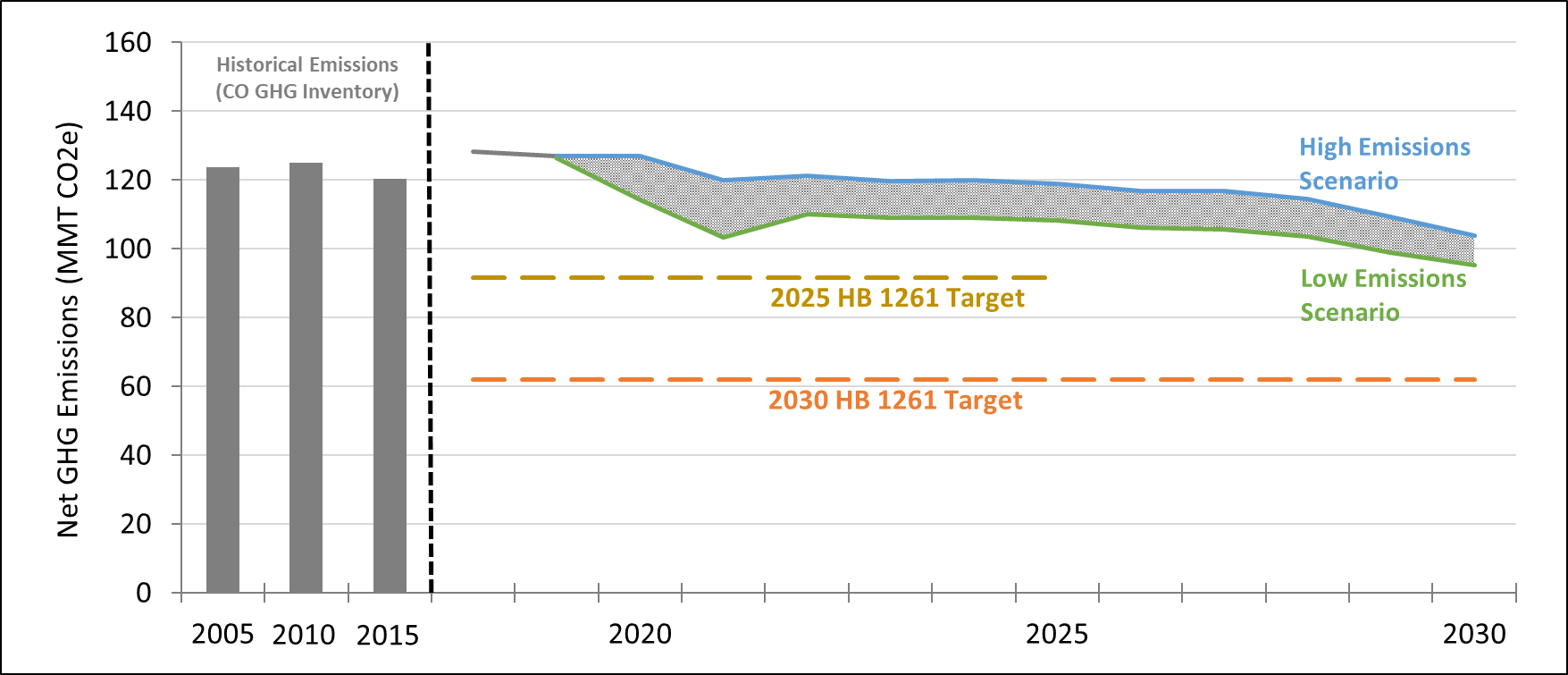

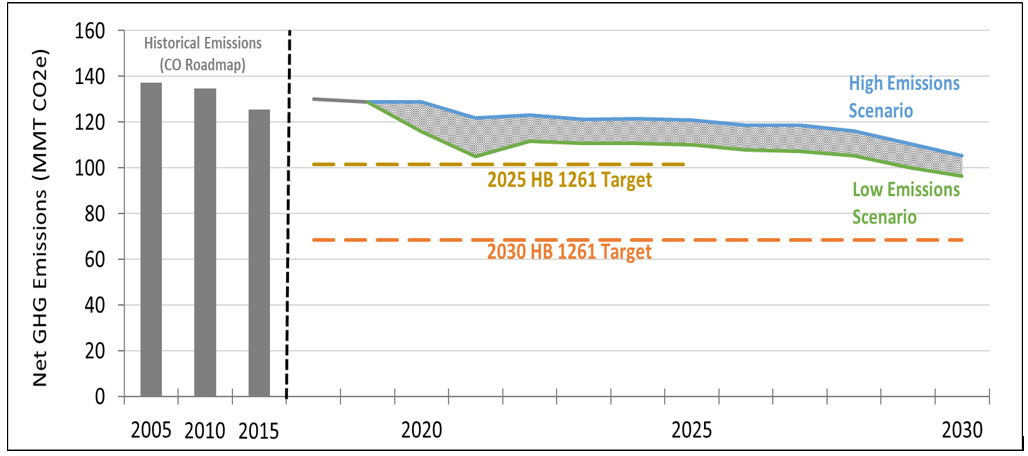

Figures 1-3 below illustrate Colorado’s emissions gaps using three different estimates of historical emissions to establish the target emissions levels. Since Colorado’s targets are determined relative to emissions in 2005, the estimate of historical baseline emissions determines the target. Figure 1 shows the emissions gap using historical estimates based on EDF’s analysis using data from Rhodium Group’s U.S. Climate Service. Figure 2 uses the comparable 2005 baseline from Colorado’s official Greenhouse Gas Inventory. In Figure 3, the state’s unofficial new baseline data moves the goalpost for reduction targets, but still reveals a substantial gap. In all three figures, future projections are based on EDF’s analysis using data from Rhodium Group’s U.S. Climate Service.

Figure 1: Colorado Economy-Wide Net Emissions and Targets

Figure 2: Colorado Economy-Wide Net Emissions and Targets, Adjusted with the State’s 2019 GHG Inventory Baseline

Figure 3: Colorado Economy-Wide Net Emissions and Targets, Adjusted with the State’s Roadmap Baseline

Any way you look at EDF’s updated analysis, Colorado’s current trajectory falls significantly short of fulfilling its climate commitments, absent more ambitious policy action to reduce emissions.

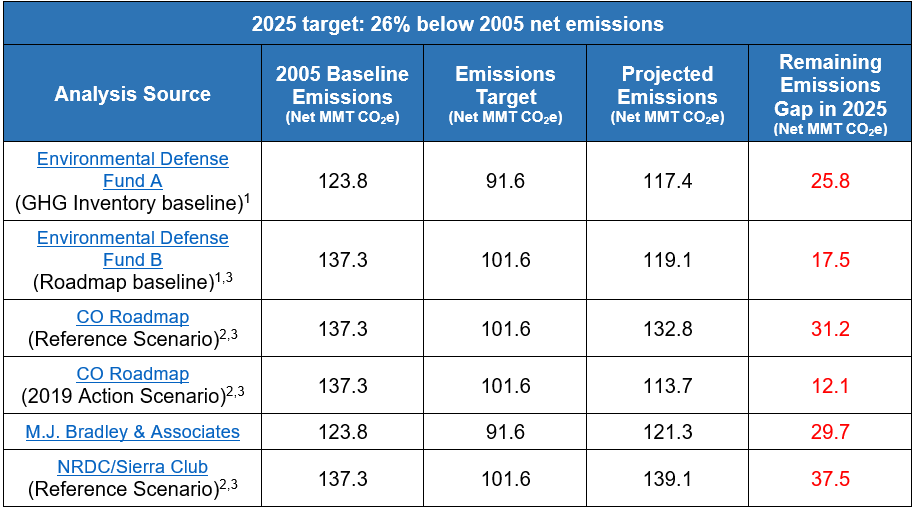

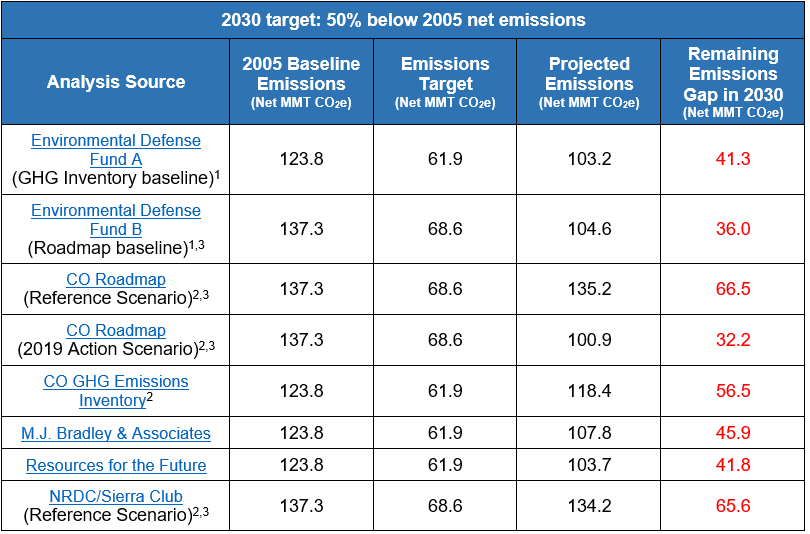

Other analyses from other organizations and the state reach a consistent conclusion. Tables 1 and 2 compare net emissions gaps from various analyses, including the Polis administration (in the 2019 Colorado GHG Emissions Inventory and the “Roadmap”), Resources for the Future, M.J. Bradley & Associates, and NRDC, Sierra Club, Evolved Energy Research, and GridLab. For background, the analyses pull the 2005 baseline emissions from two sources: the CO GHG Inventory and the revised baseline developed for the CO Roadmap. The EDF A, M.J. Bradley & Associates and RFF analyses use baseline emissions as reported in the CO GHG Inventory. The EDF B, CO Roadmap analyses and the NRDC/Sierra Club report use the revised baseline.

Table 1: Net Emissions Gaps in Colorado, 2025

Table 2: Net Emissions Gaps in Colorado, 2030

While projections vary based on assumptions that go into the analysis, the takeaway is the same: Colorado’s current policies are not enough to meet its quickly approaching deadlines in 2025 and 2030. This holds true even when significantly underestimating the task at hand. Governor Polis’ recently released draft “Greenhouse Gas Pollution Reduction Roadmap” unfortunately includes a “2019 Action Scenario” that is positioned as a “business-as-usual” (BAU) emissions trajectory despite being based on aspirations that are not backed up by current law. For example, the state assumes that—without any binding policies—it would achieve its goal of 940,00 electric vehicles on the road by 2030.

Time is running out

While Colorado is not the only state falling behind on meeting its commitments, it does stand out in one critical way. Colorado is one of 24 states, plus Puerto Rico, that have joined the U.S. Climate Alliance, a bipartisan coalition committed to implementing policies that advance the goals of the Paris Agreement, including achieving reductions of at least 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025 —the intended near-term contribution for the U.S. Louisiana, too, has made a commitment to reduce emissions to similar levels by 2025, though it is not formally a part of the alliance. Many of these states also have committed, either by executive order or in statute, to additional reductions by 2030 and 2050.

Beneath the high-level commitments, EDF’s report shows that, collectively, states that have made climate commitments are not on track to cut emissions consistent with critical science-based reduction trajectories by 2030. They are also off track for achieving the original U.S. commitment under the Paris Agreement for 2025. Yet unlike most other states with these climate commitments, Colorado’s environmental regulators have an express, statutory directive requiring them to develop regulations to secure these emission reductions. They are required by law to meet these targets – and Coloradans are counting on it.

From the west slope to metro Denver, polling shows overwhelming support for the AQCC to adopt strong rules within the next year that will guarantee that the state hits its carbon emissions targets—underscoring a demand for action that has only grown with record-breaking wildfires and unsafe breathing conditions plaguing the state for much of the second half of 2020.

Analysis after analysis, as well as polling, all highlight the urgent need for a comprehensive policy framework that can cut emissions at the pace and scale required under law. The Polis administration and AQCC are running out of time to deliver the leadership that Colorado needs.

In Part 3 of this series, we’ll break down EDF’s new petition for a legally-binding, declining emissions limit across Colorado’s major sources of climate pollution and how it can help the state deliver on its goals.