Richard Denison, Ph.D., is a Lead Senior Scientist.

[I delivered a shorter version of these comments at the September 22, 2021 webinar titled “Hair on Fire and Yes Packages! How the Biden Administration Can Reverse the Chemical Industry’s Undue Influence,” cosponsored by Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER), NH Safe Water Alliance, and EDF. A recording of the webinar will shortly be available here. The webinar, second in a series, follows on EPA whistleblower disclosures first appearing in a complaint filed by PEER that are detailed in a series of articles by Sharon Lerner in The Intercept.

The insularity of the New Chemicals Program – where staff only interact with industry and there is no real engagement with other stakeholders – spawns and perpetuates these industry-friendly and un-health-protective policies.

I have closely tracked the Environmental Protection Agency’s New Chemicals Program for many years. Reluctantly, I have come to the conclusion that the program does not serve the agency’s mission and the public interest, but rather the interests of the chemical industry. Despite the major reforms Congress made to the program in 2016 when it overhauled the Toxic Substances Control Act, the New Chemicals Program is so badly broken that nothing less than a total reset can fix the problems.

Revelations emerging through responses Environmental Defense Fund finally received to a FOIA request we made two years ago, and through the disclosures of courageous whistleblowers who did or still work in the New Chemicals Program, confirm what I have long suspected, looking in from the outside. The program:

courageous whistleblowers who did or still work in the New Chemicals Program, confirm what I have long suspected, looking in from the outside. The program:

- uses practices that allow the chemical industry to easily access and hold sway over EPA reviews and decisions on the chemicals they seek to bring to market;

- has developed a deeply embedded culture of secrecy that blocks public scrutiny and accountability;

- employs policies – often unwritten – that undermine Congress’ major reforms to the law and reflect only industry viewpoints; and

- operates through a management system and managers, some still in place, that regularly prioritize industry’s demands for quick decisions that allow their new chemicals onto the market with no restrictions, over reliance on the best science and protection of public and worker health.

Many of the worst abuses coming to light took place during the Trump administration, and it is tempting to believe the change in administrations has fixed the problems. It has not. The damaging practices, culture, policies and management systems predate the last administration and laid the foundation for the abuses. Highly problematic decisions continue to be made even in recent weeks.

I am encouraged by recent statements and actions of Dr. Michal Freedhoff, Assistant Administrator of the EPA office that oversees TSCA implementation. They clearly are moves in the right direction. But it is essential that the deep-rooted, systemic nature of the problem be forthrightly acknowledged and forcefully addressed.

Let me provide some examples of each of the problems I just noted.

Industry calls the shots

I blogged earlier about documents EDF obtained through a FOIA request that showed collusion between industry law firms and trade associations and EPA officials on actions pertaining to safety reviews of new chemicals. EPA actively sought input from industry – but no other groups, such as public interest advocates – on what changes companies wanted to see made to the reviews.

EPA’s response to our second FOIA request and disclosures by the whistleblowers reveal something even more disturbing: EPA regularly shares with companies drafts of the hazard, exposure, and risk assessments it develops when reviewing their new chemicals, allowing and even encouraging them to dispute any findings they don’t like. When the companies’ lawyers don’t like the EPA scientists’ responses to their complaints, they simply elevate the issue to higher-ups.

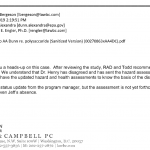

One document we got is an email exchange between then-EPA chemicals office head Alexandra Dunn and the chemical industry lawyer Lynn Bergeson. Bergeson writes to complain about EPA redoing its assessments of one of her client’s new chemicals. She is concerned that her firm does “not yet have the updated hazard and health assessments to know the basis of the disagreement” and that the revised draft risk assessment is “not yet forthcoming” (emphases added), and she alerts Ms. Dunn that “we may need to elevate this case.” Click below to view.

This example illustrates that EPA’s draft documents had been shared with the industry law firm, that the firm had a clear expectation that it would be given the updated documents to review, and that it was willing and able to protest anything it didn’t like all the way to the top.

The whistleblowers describe in detail how this industry access was institutionalized: EPA managers took to labeling cases where a company objected to EPA scientists’ draft assessments and findings as “Hair on Fire,” and pressured the scientists to water down or remove concerns they found. Or the managers would simply override the scientists and overwrite the documents themselves.

I ask you: In what universe is it acceptable for the very entities EPA is supposed to be regulating to be allowed such influence? The conflict of interest couldn’t be more blatant.

A culture of secrecy

I spoke last time about the behind-closed-doors, bilateral way in which the New Chemicals Program conducts its business, which wholly locks the public out of the room.

Another way EPA locks out the public is by not providing timely access to information companies submit on their new chemicals and to the reviews EPA conducts. And even when EPA does provide such documents, they are often so heavily redacted – to remove claimed “confidential business information” (CBI) – as to be indecipherable. While TSCA allows some information to be claimed confidential, EPA continues to allow companies to withhold from the public health and safety information that TSCA mandates be disclosed – despite EPA statements that it screens applications to prevent this.

Documents EPA posted this summer to its ChemView database on a PFAS chemical that a company seeks to expand the use of include a Safety Data Sheet (SDS). SDSs are the poster child for health and safety information that must be disclosed under TSCA. Yet the company submitted a completely redacted SDS, consisting of a single page containing a single word: “Sanitized.” EPA accepted the company’s application and started the clock running on its review.

The 2016 TSCA amendments require companies to substantiate their claims that information they submit qualifies as confidential. Yet this same company completely redacted its substantiation – again reducing it to one page with only a single word: “Sanitized.” The public doesn’t even get to know why the company believes it can withhold the entire SDS for its chemical. EPA should have immediately declared this company’s application invalid and rejected it; instead, even as the clock ticks on EPA’s review, the public has illegally been denied access to even the most basic health information about the chemical.

The whistleblowers describe another dimension of secrecy within the agency: their inability to communicate with other EPA scientists who have expertise they need. Under the last administration, managers actually barred such communications, which we understand the new EPA leadership has moved to reverse. But the draconian measures EPA has put in place to restrict which staff are allowed access to CBI are – and are used by managers as – a barrier that limits EPA scientists’ ability to consult with each other and conduct robust reviews of new chemicals.

De facto policies contrary to amended TSCA

One of the biggest changes that Congress made to new chemical reviews when it reformed TSCA in 2016 was to ensure that a chemical couldn’t slip into commerce unregulated merely because EPA lacked sufficient information about its safety. Before the reforms, unless EPA had enough data to show potential risk, it simply “dropped” the chemical from further review and allowed it onto the market. In amending TSCA, Congress directed EPA to determine whether it had sufficient information and, if not, to impose restrictions on the chemical and/or require a company to test it to identify any potential risks.

Sadly, this clear statement of Congress’ intent has been systematically thwarted. It has been years since EPA has imposed a single testing requirement on any company applying to bring a new chemical to market. Several years ago, EPA stopped posting its initial determinations that data on a chemical were insufficient, and has responded to our recent requests that it restore this practice by saying it no longer makes such interim calls. Indeed, the whistleblowers’ disclosures confirm that managers have made it all but impossible for EPA scientists to make the finding that EPA lacks sufficient information on a chemical, no matter how little information is available. Instead, those new chemicals end up on the market – just like they did before TSCA was updated.

Because it lacks data on many new chemicals, EPA frequently relies on so-called “analog” chemicals – the identities of which are usually hidden from the public – to predict the risks of the new chemicals. No attempt is made by EPA to communicate its level of confidence in how well that analog mirrors the properties of the new chemical; nor is any testing of the new chemical ordered that could confirm or negate the predictions EPA made based on the analog – something that was occurring in the months immediately following the 2016 reforms.

Avoiding testing at all costs – a big industry priority – has become a de facto EPA policy, despite Congress’ mandate and its expansion of EPA’s testing authority. Perversely, this creates a huge disincentive for industry to develop more information, which could inform and expedite EPA’s reviews, because companies can expect to get approval of their new chemicals without doing any testing.

We recently were shocked to learn of another disturbing de facto policy on new chemicals: This summer EPA issued “not likely to present unreasonable risk” determinations for two new chemicals that contain verbatim the language used hundreds of times in those issued under the last administration. EPA has again dismissed occupational risks it identified based on an assumption that workers will wear personal protective equipment (PPE) – despite that fact that their employers are not required to provide it (see here and here). These very recent decisions allowing the chemicals to enter commerce without conditions directly contradict EPA’s announcement that it is reversing this policy.

When we inquired, what we learned was even more disturbing: EPA categorically assumes that chemicals that cause skin and eye irritation do not present an unreasonable risk. Why? Because it assumes workers will “self-limit” their exposures to avoid the effect. And on that basis EPA once again assumes workers will always wear PPE. I have heard the chemical industry make this self-serving argument for decades that workers will simply protect themselves. But I was stunned to hear it echoed by senior career staff in the New Chemicals Program. I asked whether these policies are written down; I was told no. I asked whether EPA had discussed these positions with anyone from the labor community, but got no response. (Labor would no doubt have a different take on workers’ ability to act on their own to avoid chemical exposures and keep their jobs.)

I can only conclude that the insularity of the New Chemicals Program – where staff only interact with industry and there is no real engagement with other stakeholders – spawns and perpetuates these industry-friendly and un-health-protective policies.

Management structure that rewards speed over protection of the public

The whistleblowers have documented a management system in the New Chemicals Program that prioritizes and rewards staff performance based only on the number and speed of completion of new chemical reviews. Lacking are metrics that reflect TSCA’s “primary purpose … to assure that [ ] innovation and commerce in [ ] chemical substances and mixtures do not present an unreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment.”

This same disparity can be seen in the current administration’s 2021 proposed budget for EPA. While describing the program’s goal as “preventing the introduction of any unsafe new chemicals into commerce” (p. 12), the only metric to be used to measure program performance is the percentage of final new chemical determinations completed within 90 days – and the goal for that metric is proposed to be increased from the current 80% to 100% in FY22 (p. 43).

What is to be done?

In my remarks during the last webinar, I offered some recommendations that I briefly reiterate here:

- Provide the public with its scientists’ appraisal of the safety of each new chemical; if initial concerns they identify are later resolved, EPA should be clear about what changed. This is vital to increasing the accountability of the review process.

- Give the public timely access to all documents related to each new chemical, subject only to redaction of information that is both eligible and meets all TSCA requirements for withholding as confidential.

- Retain and internally track all versions of new chemical assessments and fully document and justify the basis for any changes made to them.

- Provide a meaningful opportunity for the public to have input into EPA decisions on new chemicals. This is critical to begin to dismantle the strictly bilateral, behind-closed-doors mode of operation of the program.

- Thoroughly investigate whether program managers used their positions to coerce agency scientists, improperly override their assessments, or sideline or retaliate against them. If so, those managers should not be permitted to retain their positions of authority.

Let me add several more here:

- Immediately cease sharing risk assessments and other review documents with companies or their representatives, who – to state the obvious – have a massive vested financial interest in the outcome of EPA’s reviews and decisions on their chemicals.

- Declare invalid and reject any new chemical application that redacts health and safety or other information not eligible for confidentiality under TSCA.

- Restore the ability of scientists across EPA to consult with each other regarding scientific issues they face in new chemical reviews. Where that entails sharing of CBI, EPA needs to find a way to do so while maintaining protection for that information.

- Immediately comply with TSCA’s mandate to impose restrictions on or require testing of any new chemical where scientists reviewing it find there is insufficient information to conduct a reasoned evaluation.

- Rescind the de facto policy that dismisses irritation risks to workers exposed to a chemical; and fully implement the reversal in the prior policy that erroneously assumed all employers will provide and workers will wear protective equipment. EPA should instead implement the Industrial Hygiene Hierarchy of Controls (HOC) embodied in both OSHA policy and that of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

- Develop metrics that reward new chemical reviewers and managers based on preventing risky chemicals from entering commerce or imposing needed testing and restrictions to identify and mitigate risks.

- Establish a conflict of interest-free council of independent scientists drawn from EPA, but outside of OCSPP (the office that houses the New Chemicals Program), and from outside the agency, to help resolve scientific disputes between EPA scientists and managers.

These recommendations are just a start at what will be needed. Paramount is the need to break industry’s grip on the New Chemicals Program – critical if EPA is to restore the program’s scientific integrity and public trust in its operation and decisions.