Lead service lines must be replaced as soon as possible to protect children

Tom Neltner, J.D., is Chemicals Policy Director.

Two years ago, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) asked me to serve on its new multi-stakeholder workgroup to develop recommendations to improve the agency’s 1991 lead in drinking water rule. I had heard about problems with the rule but was unfamiliar with the details. My efforts to prevent lead poisoning over the past 20 years at the federal, state, and local levels focused on lead-based paint and consumer products. Lead pipes were new to me. Knowing the dangers of any lead exposure all too well, I was happy to help.

What I learned was disturbing. The rule’s shortcomings became clear when a utility representative presented a chart showing the lead levels from homeowner sampling over the years. While few in number, some lead levels in the water were literally off the scale, in the hundreds of parts per billion (ppb). And yet a utility operating a public water system would be in compliance with the rule as long as less than 90 in 100 samples were below 15 ppb. The only required action would be an alert by the utility to the homeowner. It became clear to me that lead could be found in water at extremely high levels, but these spikes—and potentially substantial public health risk—may not be investigated and corrected.

EPA’s own studies confirmed the problem. It turns out that the highest lead levels were often missed because the sampling method focused on the water in the interior plumbing and not the water sitting overnight in the lead service line – the pipe that connects the main in the street to the house. In addition, only 50 or 100 samples every three years were required; too few taken too infrequently to identify problems in a large city in a timely manner.

The primary source of lead is service lines made of lead pipe that connect to 6 to 10 million homes. Lead in brass fixtures and solder in interior plumbing present a risk, but it is much smaller when compared to pipes made of solid lead. The corrosion control treatment of water, required for most utilities in the mid-90s, reduces lead levels in drinking water by creating a protective coating inside the pipe. While the coating is effective, it is insufficient to prevent unpredictable releases of huge amounts of lead when lead pipe is disturbed or the water chemistry changes. At one of the EPA working group meetings I participated in, an agency staffer indicated that the vibration you feel in your home when a large truck drives down the street might be enough to dislodge some of the protective coating that corrosion control provides.

While there are doubts about the reliability of corrosion control, there is no doubt that lead is unsafe at any level. In the past 25 years, the evidence that lead, even at low levels, poses a significant risk to a child’s brain development has become only more compelling. Lead can harm brain development in young children resulting in learning and behavioral problems and reduced IQ for the rest of their lives.

With more than 500,000 children having elevated blood lead levels, as many as 10 million homes with lead service lines, and 24 million homes with lead-based paint hazards, our country has work to do. A priority needs to be children in poor households who are three times more likely to have elevated blood lead levels and African-American children who are twice as likely to show elevated blood levels as their white counterparts.

Eighteen months after that first meeting, the workgroup adopted a final report recommending that EPA overhaul the current rule to make lead service line replacement a top priority rather than a last resort and to better manage systems and pipes in the interim. The ultimate goal is to replace all lead service lines. A thoughtful dissent from a public interest advocate supported lead service line replacement but argued the recommendations did not do enough to protect people in the interim and ensure all lines are replaced.

After the report was released in August 2015, I first learned of the tragedy in Flint, Michigan. In November, after hearing from people in Flint, EPA’s National Drinking Water Advisory Council (NDWAC) told the agency that it should implement the report and laid out ten enhancements to address the lessons learned.

EDF is committed to working on solutions that accelerate lead pipe removal. These include:

1. Overhaul the Lead and Copper Rule

EPA needs to overhaul the rule based on NDWAC’s recommendations. To avoid delays from a change in administration, Congress should establish deadlines to ensure the agency finishes the job.

2. Cooperative Effort to Accelerate Lead Pipe Replacement

Communities need to begin now to replace lead service lines as part of an aggressive long-term program. This program must be a shared responsibility among the local utility, the public health community, residents who must cooperate since the lines are partially on their property, and the community’s elected leaders.

The federal government can play an important role in supporting this cooperative effort by:

- Expanding the existing programs that are focused narrowly on lead-based paint to include lead in drinking water so that families can make informed decisions about both paint and pipes.

- Requiring sellers to disclose to prospective homebuyers whether the home has a lead service line or not.

- Providing low-income residents financial assistance to replace their portion of lead service lines.

- Updating EPA and Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) lead-based paint standards to ensure they are based on the latest research and are consistent with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) guidance.

- Restoring full funding to CDC’s and HUD’s lead and healthy homes program to support state childhood surveillance programs and lead hazard control for pipes and paint in low income housing.

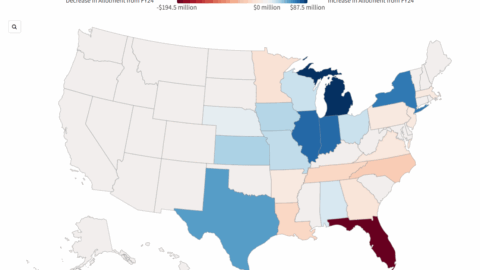

- Providing utilities access to a fully-funded loan program to replace lead service lines without undermining other critical water infrastructure projects.

We have come a long way in reducing lead exposure, but until we protect everyone the job won’t be finished. The problem is clear – these is no safe level of exposure to lead – and the solutions are apparent – the lead service lines must be replaced. There is no reason to let lead service lines remain a threat to our children. For more information go to www.edf.org/leadpipes.