Last year’s hurricane season was the most destructive disaster season in U.S. history, causing $265 billion in damage and forcing more than one million Americans from their homes.

As climate change causes weather to get more extreme, coastal communities across the country are struggling to find cost-effective solutions to enhance their resiliency to storms and develop new ways to finance that work.

How can we help make coastal communities more resilient more quickly? How can we engage the private sector in coastal resiliency efforts and generate a financial return for investors?

Together with my EDF colleagues and partners, I set out to explore how one innovative financing mechanism – environmental impact bonds – might help.

How do you fund restoration for a disappearing coast?

Coastal resiliency challenges are especially problematic along the Gulf Coast. In Louisiana, an area of land the size of a football field turns into open water every 100 minutes. Since the 1930s, the state has lost nearly 2,000 square miles of land and will lose another 4,000 square miles over the next 50 years if nothing is done. As the land disappears, so does the storm surge protection it provides communities.

Fortunately, Louisiana has a plan to rebuild and protect its coast, but it has not yet identified all the funding needed to fully implement the plan. That’s where environmental impact bonds come in.

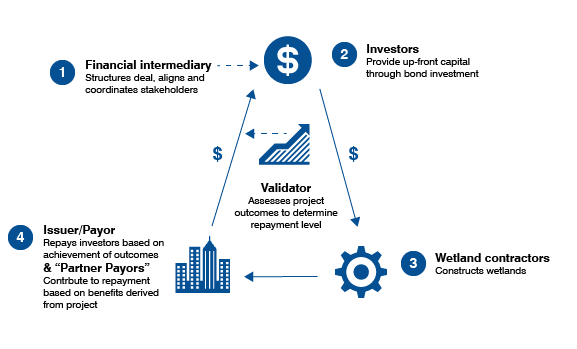

Environmental Defense Fund and Quantified Ventures, the financial intermediary that designed the nation’s first environmental impact bond, looked into how environmental impact bonds could help the state of Louisiana fund wetland restoration projects sooner while also involving the private sector in helping finance the projects.

Not your normal bond

Environmental impact bonds are a form of pay-for-success debt financing in which investors purchase a bond and repayment to investors is linked to the achievement of a desired environmental outcome, such as reduced land loss.

By pursuing a pilot environmental impact bond transaction, Louisiana has the potential to be a world leader in using private investment for coastal resilience – demonstrating how the private sector can partner with government agencies to implement coastal restoration projects and generate a financial return for investors.

Environmental impact bonds can be a vital tool in the coastal restoration and resiliency toolbox. Share on XEnvironmental impact bonds expand the range of possible coastal restoration financing tools beyond typical municipal bonds. Most importantly, they can help Louisiana and other coastal states restore their coastlines more rapidly and for less money by:

- Using capital more efficiently – building wetland restoration projects sooner rather than later, when the projects will be more expensive to build due to inflation, erosion and/or land subsidence.

- Involving local asset owners who benefit from wetland restoration projects – such as nearby land owners, leasers or businesses – in the financing of those projects.

- Rewarding high-performing wetland restoration projects and the contractors who build them, thereby encouraging the construction of high-quality restoration projects.

- Building an evidence base for the value of wetlands for reducing land loss and therefore reducing storm damages.

This environmental impact bond model can be scaled and replicated to support restoration efforts across coastal Louisiana, the Gulf Coast and beyond to help areas coping with sea level rise, land loss and damaging storms.

Environmental impact bonds will be a vital tool in the coastal restoration and resiliency toolbox.

This project was funded by NatureVest, the conservation investing unit of The Nature Conservancy, through its Conservation Investment Accelerator Grant.

2 Comments

It would be a much more impactful article if an actual success story example had been given, rather than a flow chart giving a rather abstract explanation of how it works. The everyday person needs to understand. Then they are more apt to put their hard-earned funding into it.Not meaning to be critical, but this narrative seems targeted toward more sophisticated investors, yet talks about engaging local landowners who may be less sophisticated and poor. But maybe this idea will gain momentum.

Bob, It would be a far more compelling story if we could present an example of how an environmental impact bond funded coastal wetland restoration, but such a transaction hasn’t yet occurred. Our goal is to set the stage for a pilot transaction. By showing that an EIB is feasible because it can be designed to be economically attractive to all the parties – investors, partners and the state – we aim to encourage Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority to pursue an actual transaction. To your point, there has been a successful EIB that funded installation of green infrastructure to help the District of Columbia Water and Sewerage Authority (DC Water) manage storm water runoff. We looked to the experts involved with that EIB to help us conceive this pilot Louisiana wetland restoration EIB. We believe these two EIB models can be used by other places facing similar challenges and looking for innovative ways to finance resilience projects that provide environmental benefits. Initially, we think participants in EIB transactions will be major businesses with coastal properties, and investors will be impact investment firms that seek an environmental or social benefit in addition to a set interest rate and repayment over a period of time. In the future, with more experience with EIB transactions, it may be possible to design an EIB that would involve homeowners or homeowner associations and be attractive to individual investors.