I recently participated on a panel discussion with a provocative title: “Elite Food Consumers: A Force for Environmental Good?” The panel was moderated by The Washington Post columnist Tamar Haspel and organized by the Breakthrough Institute.

It was a great discussion because there is no doubt that consumer preferences are changing food – and not just for elite consumers. Even the larger and more affordable food retailers are responding to new consumer demands for how food is produced, what ingredients it contains and how products are marketed. But consumer choices alone won’t reshape the food system.

Minimizing the environmental footprint of agriculture – in ways that don’t hurt farmers’ profitability or consumers’ pocketbooks – will require additional levers.

Limitations of food labels and certifications

The USDA organic seal is the most prevalent example of consumer food labels, but it has limited leverage for improving environmental outcomes. While the organic segment has grown rapidly, it accounts for just over five percent of food purchases.

As Ms. Haspel noted during our panel discussion, most consumers who purchase organic food do so because of perceived health benefits, not because of environmental considerations.

The organic label creates value for a specific set of farming practices, but it does not allow growers the flexibility to adapt to new technology innovations in food production, as was demonstrated by the recent protracted negotiations over whether hydroponic lettuce counts as organic lettuce.

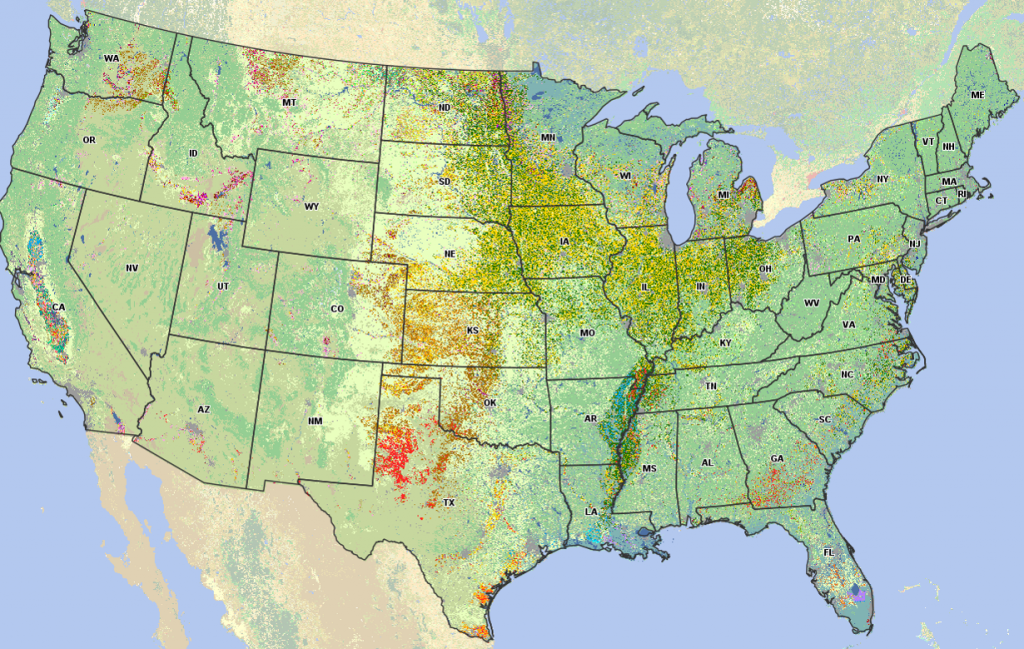

Food labels can’t capture the diversity or scale of agricultural impacts on the environment. Take fertilizer pollution as an example. Nutrient runoff is a risk whether farmers use chemical or organic fertilizers. Reducing fertilizer contamination of drinking water, rivers, lakes and places like the Gulf of Mexico will require mainstreaming conservation practices on hundreds of millions of acres of land, not just on the less than one percent of farmland that produces organic food or other specialty labeled products.

[Tweet “Elite food consumers won’t make sustainable ag the norm. Here’s what will.”]

International influences on domestically grown food

Corn and soy comprise the largest portion of agriculture’s environmental impact. But these crops are out of sight and out of mind for many consumers. They primarily go into animal feed or biofuels, which account for 40 percent of corn output.

Moreover, much of the corn and soy harvest trades on global commodity markets, so U.S. consumers aren’t the only influence on farm practices. This is particularly true for soy, 60 percent of which is exported, primarily to China.

While tariffs and a growing trade war are causing problems that will inevitably affect U.S. agriculture, there will always be a significant segment of agricultural production that sells to lower value markets both at home and abroad.

Ultimately, we cannot look only to U.S. consumers who are willing to pay a price premium to be the primary drivers of on-farm environmental sustainability. There are bigger forces at play.

USDA’s National Agricultural Statistics Service estimated that U.S. producers planted 89.1 million acres of corn (yellow in the map above) and 89.6 million acres of soybeans (green in the map above) in 2018.

How to scale sustainable agriculture

Consumer-facing companies like Walmart and Campbell Soup Company are also creating demand in their supply chains for sustainably grown grain. Food companies and agribusinesses have committed to improved practices on more than 20 million acres of corn, halfway to what we’ve calculated to be the tipping point for sustainability to become the norm. We’re working with organizations like the National Corn Growers Association to translate those commitments into on-farm action.

In addition to free market forces, there is great potential for federal policies and programs to shift market signals in favor of more sustainable ag practices. This is an area ripe for growing attention and investment.

USDA currently spends approximately $5 billion per year on conservation programs, amounting to just under nine percent of the department’s budget for agriculture (excluding nutrition and forestry budgets). This compares to the more than $20 billion that USDA budgets for commodity programs, crop insurance and farm loans.

Public investment is critical to installing and managing in-field and edge-of-field natural infrastructure such as filters and buffers that reduce nutrient runoff. Farmers take on risk by changing production practices, and public investment can help provide incentives and safety nets.

We won’t get there by staying within the conservation box of the farm bill. We need to think of conservation as a standard practice across core farm programs. We also need to increase conservation funding across these programs to allow our nation’s farmers and ranchers the ability to adapt to a changing climate.

The combination of market forces and public funding is a powerful one that can ultimately make the U.S. ag economy stronger and more resilient in the long run.

One Comment

We organise “22nd Euro Global Summit on Food & Beverages” (Euro Food-2019) at London, UK from February 28 to March 2, 2019 that is focused around the theme “Next Gen of Food Innovation”. The conference provides a lucrative platform and opportunity to meet experts around the globe. We have multifarious platform available: Speaker /Delegate/Exhibitor/media Partner/Workshops/Symposiums /Poster/E-poster/Video Presentation etc. Kindly let us know your interest so that we can let you know the further procedure. For More Web: https://food.global-summit.com/europe/