Three threats to the monarch butterfly’s winter habitat and what we can do about it

Just as some people travel great distances to spend the holiday season with family and friends, monarch butterflies, too, make a long journey to spend the winter gathered together in the oyamel fir forests of Mexico.

The eastern population passes through Oklahoma and Texas on its annual migration south, stopping periodically to fuel up on nectar, ultimately reaching their destination in the mountains of central Mexico.

Unfortunately, the monarch’s winter home is under stress, which has contributed to a 90-percent decline in the species’ population over the last two decades.

Climate change

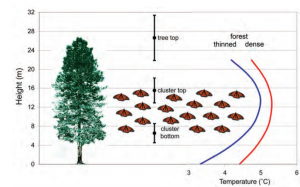

The monarch butterfly’s overwintering habitat is made up of oyamel fir forests which thrive only at high altitudes on mountains where the climate tends to be cooler. If the temperatures are too high, monarchs expend their fat reserves more quickly and are less likely to make it to their Texas breeding grounds at the onset of spring. But temperatures that are too cold are just as devastating to monarchs.

The dense canopy of the oyamel fir forests maintains the microhabitat necessary for monarchs by acting as a blanket, keeping them warm enough at night by retaining heat from the ground, and acting also as an umbrella, which protects them from rain, wind, and snow.

Climate change has the potential for diminishing this blanket and umbrella, because as temperatures rise and water supplies diminish, the forests will become stressed and more susceptible to disease and pests. As trees die off, they could create a hole in the protective canopy. This is already taking place in the lower range of some forests.

Over time the climatic conditions will have changed so much that suitable habitat for the firs will shrink and shift upward along the mountain range. It would take many generations before the trees could migrate to these regions – far longer than is necessary to keep up with climate change.

[Tweet “3 threats to the monarch butterfly’s winter habitat, and what we can do about it, via @GrowingReturns @audarcher https://edf.org/hC7”]

Extreme weather

The population of monarch butterflies has historically had drastic dips and spikes. That’s because the monarch is a sensitive species greatly impacted by extreme weather events.

In January 2002, the species experienced unprecedented and catastrophic mortality due to a rare freeze at its overwintering site in Mexico, killing an estimated 500 million butterflies. That’s more than two times the size of today’s population.

Even more recently, between 2015 and 2016, excessive winds and storms knocked down trees, which resulted in the degradation of nearly 180 acres of forest in the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve.

The frequency and duration of these extreme weather events is expected to increase with climate change, posing great threats to the dwindling population.

Forest degradation

The monarch’s overwintering habitat is also threatened by logging and the conversion of habitat for agricultural use.

In February 2010, a severe landslide killed 19 people and caused major damage in Michoacán – home of the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve. This landslide event is believed to be a result of deforestation.

Bordering the monarch’s oyamel fir forests are farming towns that are clearing land to make room for avocado orchards, cutting oak and pine trees that form a vital buffer around the mountain forests where the monarchs roost.

What can we do to protect the overwintering habitat?

Aside from mitigating human contributions to climate change, we can help monarchs adapt by protecting and restoring habitat, building resistance to key threats like invasive species and pests, and facilitating the migration of habitat to areas that will be suitable in the future.

My colleagues and I are currently working with partners from academia, government, and agriculture to increase the resilience of monarch populations in the United States, with targeted efforts to restore habitat in the Corn Belt and in key areas of Texas and California – the latter being a state that provides significant overwintering habitat for the monarch’s western population.

Bringing solutions to scale – across the U.S., Mexico and even into Canada – will be crucial to changing the monarch’s trajectory and making sure they have a safe and warm place to roost for many winters to come.

7 Comments

The article says there will be:” targeted efforts to restore [milkweed plant] habitat in the Corn Belt and in key areas of Texas and California.”

But because the number of milkweed plant stems growing in the wild numbers in the 1,000,000,000’s in the eastern and central USA and in the 10,000,000’s in the western USA, it’s not ever going to be logistically feasible for monarch enthusiasts or scientists to conduct annual milkweed plant counts on even a County, let alone Statewide or Regional scale to obtain baseline plant stem abundance data. So because baseline abundance data will never be obtainable it will likewise never be possible for the conservation groups to tell us whether the number of milkweed plant patches/stems has actually been increasing over time in any County, State or Region as a result of “restoration and recovery” efforts.

Hi Paul, you have honed in on a key challenge in monarch conservation. There is currently no national-level milkweed monitoring data or protocol, however, this is a focus of ongoing investigation by the Monarch Conservation and Science Partnership (MCSP). While the need for monitoring data is critical to accurately assess progress towards reaching milkweed stem goals, the importance of restoring and conserving monarch habitat wherever possible should not be discounted. The routine use of habitat assessment tools, such as the monarch Habitat Quantification Tool, on restored or conserved sites is an important piece of addressing this challenge.

In October and November, I wound up with a few hundred monarchs in my Cedar Park, TX backyard, feeding on tropical milkweed, cuphea, and radiant lantana. They survived until the freeze last weekend. Should I have cut the milkweed back during the migration to discourage them from staying? My whole garden is planned for pollinators, with a bed of all orange, yellow, and red natives and one of blues, purples, and pinks. I don’t like taking away any flowers before they’re spent because I want to make sure I have pollinator food available. But am I making it harder for the monarchs? Any advice you have is appreciated.

Hi Jessica, thank you for your interest in providing quality habitat for monarchs and other pollinators! Our partner, Monarch Joint Venture, recommends that if you already have tropical milkweed in your garden, prune the milkweed stalks to about 6 inches in height during the fall and winter months to discourage monarchs from establishing winter-breeding colonies. You can read more about the potential risks of growing non-native milkweeds for monarchs here.

Here in the US we should also give more attention to the threats to Monarch butterflies in their summer habitats in our country. Here in New England a now ubiquitous common weed called blackswallow wort introduced from Europe in the late 19th century produces spores that look like milkweed to Monarch butterflies. The blackswallow wort is not unsightly but it is poisonous to Monarchs because they can’t reproduce. Wider knowledge about this threat in the US would allow more and greater efforts to reduce this weed. Here in Cambridge, MA where I live there are many residents who spend much of the summer removing this vine from fences etc. I don’t know where else in the US it might be, but it is definitely a problem.

Thanks for bringing this to our attention, Colleen! This is the kind of information we will be sure to incorporate into management plans for projects enrolled in the habitat exchange. For others interested in learning more about the impacts of this invasive species on monarchs, read this flyer produced by our partner, Monarch Joint Venture.

Love the monarchs. So grateful this work is being done to protect them. Thank you.