I’m going to take you back to 2005, to a ranch in the Texas Hill Country, where Dr. Gene Murph operates an 80-head cattle operation on 1,300 acres of rangeland.

The ranch is vast, with rolling hills and wooded ravines. The only sounds on the ranch are those of cattle mooing in the pastures and birds trilling in the trees. If you listen closely enough, you can hear the signature call of the golden-cheeked warbler. If you look closely enough, you can spot the bird’s sunshine-yellow face.

The golden-cheeked warbler was listed as an endangered species in 1990, making Dr. Murph’s ranch a vital stronghold for subpopulations, which nest at select sites scattered throughout 33 counties in central Texas.

Another nearby stronghold for the bird is the Fort Hood Army Base, only a few miles down the road from Dr. Murph’s ranch and home to the largest known population of golden-cheeked warblers.

Avoiding a battle over birds

In 2005, Fort Hood served as a training base for troops preparing for deployment to Afghanistan and Iraq. As you can imagine, the potential for habitat loss was a constant possibility and, at times, a limit on training at the base.

The golden-cheeked warbler, also known as the gold finch of Texas, is the only bird species with a breeding range confined to Texas. Fort Hood has the largest known population of golden-cheeked warblers.

Fort Hood needed a way to mitigate its impacts on the golden-cheeked warbler, and fast.

In partnership with the Texas Department of Agriculture and a coalition of other organizations, Environmental Defense Fund coordinated the development of a market-based credit exchange so that Fort Hood could quickly obtain offsets from nearby landowners to counteract losses from live-fire training activities and troop movement through core habitat areas.

The program, known as the Fort Hood Recovery Credit System, enrolled nearby landowners with warbler habitat on their property in a competitive reverse bidding auction, which worked as follows:

- The required acreage and potential habitat-improving practices were made known to landowners, who were then given an opportunity to send private offers or bids for projects on their land.

- Bids were submitted, specifying the minimum revenues that the bidder would need to receive, the bidder’s willingness to make a contribution (cost-sharing), and the length of the contract (10 years minimum, 25 year maximum), with more credits resulting from longer commitments. This is called a reverse auction because the winners in principle would be those who bid least.

- The final ranking of each offer took into account many factors besides cost including habitat quality, term duration and geographic proximity to Fort Hood.

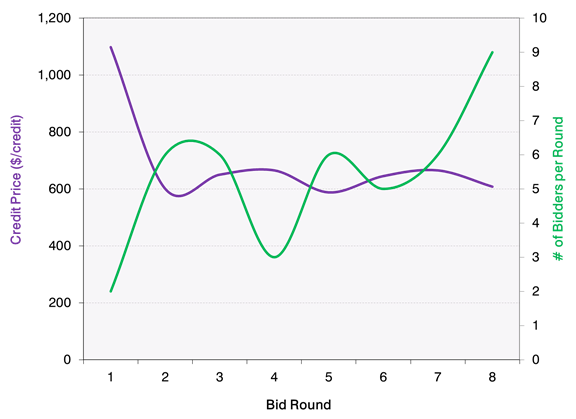

Over a three-year period, there were eight auctions, or bid rounds, conducted – one every three to four months – and there were 21 successful bidders out of a total of 44.

Total revenue to the 21 participating landowners amounted to nearly $2 million.

The first bid round of the reverse auction fixed the credit price at a relatively high level (upwards of $1,100 per credit), attracting higher turnout for subsequent bid rounds. As competition increased and landowners revealed their preferences to each other, prices normalized around $600/credit. (Economic analysis conducted by Jeremy Proville)

The Recovery Credit System was designed to connect buyers and sellers directly, putting mitigation dollars straight in the hands of participating landowners. Many of the practices that landowners adopted did not inhibit their operations or reduce revenue, so the conservation credit became an additional source of income.

Back to Dr. Murph

Dr. Murph signed up to participate in the Recovery Credit System during an early bid round, committing to several habitat-enhancing practices on his land for 10 years. His term is expiring in 2017.

In hindsight, Dr. Murph says he wishes he would have been less conservative and enrolled in the maximum term length of 25 years.

That’s because, in addition to extra income, Dr. Murph also received funds to invest in his land in ways that benefited both the golden-cheeked warbler and his property. These funds paid for fire management, gravel roads and cross fencing to improve access to and maintenance of golden-cheeked warbler habitat – all practices that either improved his cattle operations or had no impact on farm output.

The next generation of the Recovery Credit System: habitat exchanges

Learning from the novel design of the Fort Hood program and building upon its most effective and desirable features is central to the implementation of current habitat exchanges being developed for other at-risk wildlife like the lesser prairie-chicken and greater sage-grouse.

There are hundreds if not thousands of other farmers and ranchers like Dr. Murph waiting for the right incentives to unlock the immense conservation potential of America’s working lands.