In the United States, onshore oil and gas extraction operations generate nearly a trillion gallons of produced water annually. It is the largest waste stream associated with upstream development of petroleum hydrocarbons.

In the United States, onshore oil and gas extraction operations generate nearly a trillion gallons of produced water annually. It is the largest waste stream associated with upstream development of petroleum hydrocarbons.

As EDF has written in numerous posts, this wastewater from oil and gas wells can be complex and toxic. In addition to the chemicals companies use during drilling and extraction, it can contain a wide range of potentially harmful material that already existed in the ground, and can be many times saltier than seawater. There’s a lot of it, too. Some wells produce up to 10 times as much wastewater as they do oil.

Why is there so little data about what’s in it?

Historically, there hasn’t been much consideration given to contaminants in produced water as most of it has been injected into (ideally) sealed, underground wells. But as wastewater volumes increase, and as challenges arise with existing disposal options (including the fact that some disposal wells can cause earthquakes), more and more companies are looking for “new” disposal options. This includes reusing it for more energy production, or reintroducing it back into the environment for things like stream augmentation, livestock watering or agriculture. And let’s not forget, more produced water being moved from one place to another means more opportunity for accidental spills and leaks.

Shining new light on the toxicity of chemicals in produced water Share on XSuddenly, the little we know about this wastewater is a much bigger concern. What is in it? Can it be treated? Where should it be stored?

Research conducted by EDF, Texas A&M University, and the Endocrine Disruption Exchange (TEDX) and published in Environment International this month shines some much needed light into this void and represents an important first step for researchers, regulators, and other stakeholders concerned about the management of produced water.

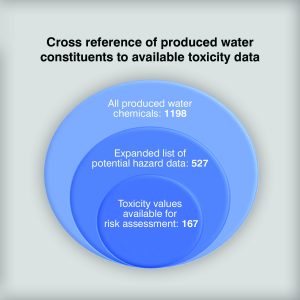

We conducted the most all-inclusive literature review to date, screening nearly 16,000 published articles, in search of data on chemicals detected in wastewater. Interestingly, what we learned from this research is that what we don’t know about chemicals in produced water is just as significant as what we do know.

What did we find?

We found that more than half of the chemicals identified in produced water have not been studied for safety or toxicity. More than three-quarters (86%) lack the data needed to complete a risk assessment, and less than 25% have standardized methods to detect or quantify them in water.

Our objective, then, was to develop a framework to identify potentially harmful chemicals and substances in order to prioritize them for monitoring, treatment and further research. Importantly, even the limited information we have today can inform fit-for-purpose reuse or treatment strategies to reduce possible human health risks and environmental impacts.

Our method yielded 23 chemicals of concern, including those with known toxicity (e.g., 1,4-dioxane and 1,1,2,2-tetrachloroethane – both suspected carcinogens), and legacy pollutants (harmful chemicals that have been banned, but are very long-lived). Importantly, some of the chemicals we identified might not be expected in produced water, and therefore aren’t necessarily being tested for, either before or after treatment.

This method of prioritizing chemicals and focusing on a subset of them provides useful insights, but does not eliminate potential concern from the broader list of chemicals.

It is, however, one of the most comprehensive resources on what we know, to-date, about produced water chemicals. Decision-makers can use this research to identify which potentially harmful chemicals require more urgent research, and which chemicals we should be setting higher standards for in order to adequately protect human health and the environment.