New Study Finds Oil & Gas Methane Emissions in the Barnett Shale Almost Twice What Official Estimates Suggest

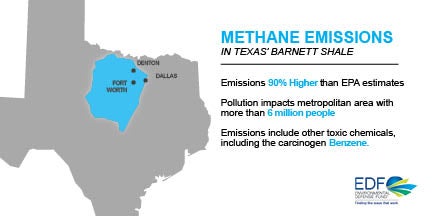

A new scientific study published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, coordinated by EDF, reports findings from the most comprehensive examination of regional methane emissions completed to date. Focused on Texas’ Barnett Shale – one of the nation’s major oil-and-gas-producing regions – the study uses a new, more accurate way to determine the total amount of methane escaping into the atmosphere from the region’s oil and gas production, processing and transportation.

A new scientific study published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, coordinated by EDF, reports findings from the most comprehensive examination of regional methane emissions completed to date. Focused on Texas’ Barnett Shale – one of the nation’s major oil-and-gas-producing regions – the study uses a new, more accurate way to determine the total amount of methane escaping into the atmosphere from the region’s oil and gas production, processing and transportation.

The result is that methane emissions in the Barnett Shale are 90 percent higher than EPA’s inventory data would suggest.

This is just one of several recent studies showing a pattern of underestimating methane emissions in locations across the country. One big reason is that conventional inventories typically fail to accurately account for very large, unpredictable emissions from leaks, malfunctions or other problems. In the Barnett study, these were the source of a large share of total emissions.

Why Methane Matters

The higher emissions rate and the agreement among measurement methods represent an important step forward in our understanding of what it will take to mitigate those emissions. Methane is the main ingredient in natural gas, and a highly potent greenhouse gas, with over 80 times the 20-year warming power of carbon dioxide.

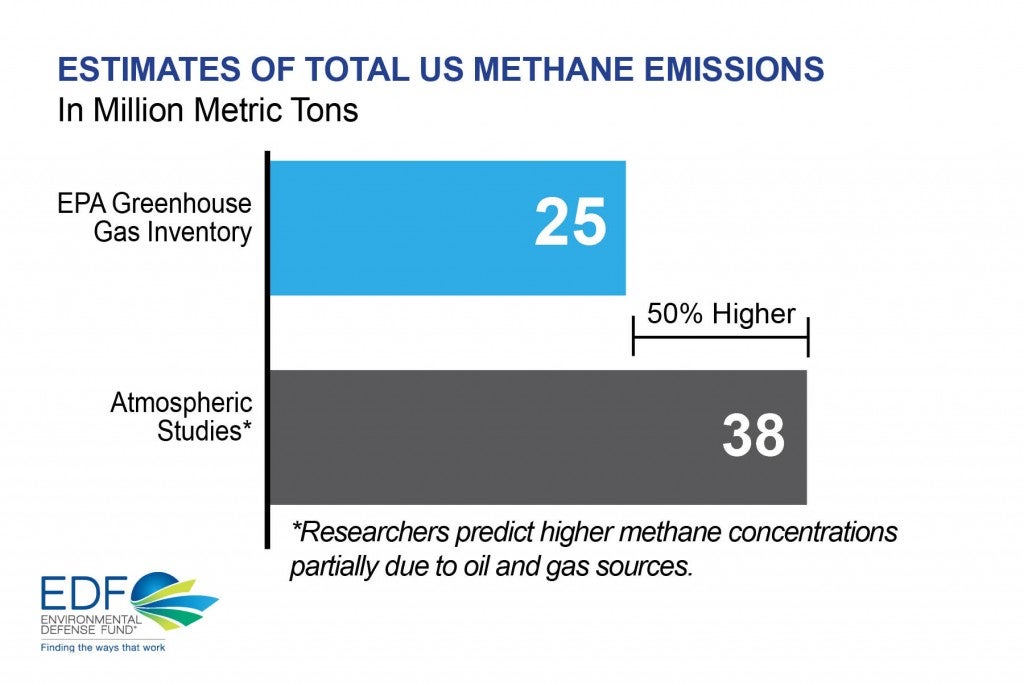

When methane leaks, the climate impact of using natural gas increases. In the case of Barnett Shale gas, based on emissions identified in the study, the climate impact is 50 percent higher over 20 years as compared to the use of natural gas in the absence of any emissions.

httpv://www.youtube.com/watch?v=traRDCjwqc8&feature=youtu.be

Getting the Full Picture

The study analyzes data from 12 papers that were published earlier this year as part of an extensive, coordinated effort among more than 10 research teams to quantify oil and gas methane emissions at a regional scale. It affirms the importance of earlier findings that the biggest emissions come from a relatively small number of unpredictable sources that are inherently difficult to anticipate.

For example, in the instance of production sites, 30 percent of those in the Barnett Shale region leak more than 1 percent of the natural gas they produce, which in turn accounts for 70 percent of overall production site emissions. This suggests that frequent and thorough inspection and repair efforts are necessary to find and eliminate methane leaks as they arise.

In this study, scientists compiled an updated, comprehensive inventory of emissions sources from across the oil and gas supply chain, and multiple research teams deployed a diversity of measurement techniques to reconcile the differences between emission rates estimated using airborne (top-down) and ground-based (bottom-up) methodologies that have previously been observed. That means scientists, policymakers and companies can now have greater certainty about methane emission rates not only in the Barnett, but also have proven methodologies that can be used to get a clear picture of emissions elsewhere.

In this study, scientists compiled an updated, comprehensive inventory of emissions sources from across the oil and gas supply chain, and multiple research teams deployed a diversity of measurement techniques to reconcile the differences between emission rates estimated using airborne (top-down) and ground-based (bottom-up) methodologies that have previously been observed. That means scientists, policymakers and companies can now have greater certainty about methane emission rates not only in the Barnett, but also have proven methodologies that can be used to get a clear picture of emissions elsewhere.

Live case in point in California

A real-life example of just how important high-emitting sources can be is taking place in California right now at the Aliso Canyon natural gas storage facility owned by Southern California Gas. For over a month, a massive leak has been pumping out about 50,000 kilograms of methane an hour – more than a quarter of the state’s estimated daily total methane emissions.

Circumstances at the aging gas storage facility – where the company pumps natural gas back underground into an old oil deposit for times when it is needed – are unique. But while extreme, it is an example of the kind of large, unpredictable leaks that occur daily throughout the oil and gas supply chain.

Based on the new research just reported as well as other studies that have taken account of super emitters, EPA’s already large national estimate of 7.3 million tons of yearly methane emissions from the oil and gas industry could be much higher (and that doesn’t even include emissions from major malfunctions like the one in California).

Addressing the Problem

Policymakers increasingly recognize the importance of better oversight of oil and gas methane emissions. In fact, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently proposed the first-ever national standards for this pollutant from new and modified oil and gas sources. Findings from this new research characterizing methane emissions in the Barnett region can help inform EPA’s rulemaking – for example, the research indicates that strong leak detection and repair requirements are critical to quickly finding high emitting sources and getting them repaired.

But most importantly, the research shows the increasing confidence we now have in dealing with a methane problem bigger than previously recognized, and that means EPA’s work is not yet over. Once a strong set of rules is created for mitigating methane emissions from new and modified sources, EPA needs to address emissions from existing sources that will still be contributing the overwhelming majority of emissions in the coming years. And, as seen in the Barnett Shale region of Texas, where the true scale of the existing problem is now well defined, that will be a significant amount.

As the measurement methods that were validated in the the Barnett research are applied in other regions across the U.S. – and the world – they will provide a much clearer picture of the state of oil and gas methane emissions, and how to best address them.

One Comment

Good luck! Here in the Barnett Shale we have had zero success in getting the state to accept the facts about gas drilling and production pollution. Your results track ours, whether they be official funded research by EPA or from NGO measurements such as reported by Shale Test. In Texas O&G rules the state. The industry has even embarked on an effort to get a new law passed that would destroy the concept of home rule in determining what activities are dangerous to the health of municipalities. This was the response to Denton banning gas drilling inside the city.

If the industry would spend as much money on alternative power source research as they do to corrupt government we’d have the problem of global warming drastically reduced in short order. But we see no real movement in this direction. Regulation is a joke at every governmental level.