This commentary originally appeared on our Texas Clean Air Matters blog.

This commentary originally appeared on our Texas Clean Air Matters blog.

I often refer to energy efficiency as being cost effective, and it is. It is always cheaper not to use energy or to get the same result while using less energy. But monetary cost savings are just one of the many benefits associated with implementing energy efficiency measures. Reduced pollution, improved health and reduced strain on our water supply are other notable benefits of energy efficiency, though they are not always taken into consideration when a utility proposes a new energy efficiency project.

At the state regulatory level, Public Utility Commissions or similar entities are required to do a cost-benefit analysis for each energy efficiency project or program that a utility proposes, in order to determine how cost effective it may be. This analysis is called an ‘energy efficiency cost test,’ and although the concept may seem straight forward, its application is based on a varying set of pre-defined criteria that are not always consistent. Furthermore, the subject of cost-effectiveness tests is sensitive in the utility sector, because it’s at the core of how energy efficiency programs are valued.

There are several different types of energy efficiency cost tests that differ slightly and are often customized to reflect a state’s values. Before diving into the options, it’s important to note that a cost-effectiveness test of some sort is a necessary measure as more and more states implement ratepayer-funded energy efficiency programs. Customers need to know that the programs they’re paying for are delivering the promised benefits, and regulators need to ensure that the costs paid by the customers are justified.

Not All Tests Are Created Equally

To varying degrees, states choose resource cost tests that evaluate the cost of an energy efficiency project or program compared to the value of energy that its implementation saved (or didn’t consume). Furthermore, as homes and businesses adopt more customer facing, demand-side resources, like demand response and distributed generation (e.g. rooftop solar panels), resource cost tests may evolve to better evaluate the cost effectiveness of these new technologies and methods. Also, some energy efficiency programs are exempt from the cost-effectiveness tests, such as those that target low-income communities and test new technologies in the marketplace.

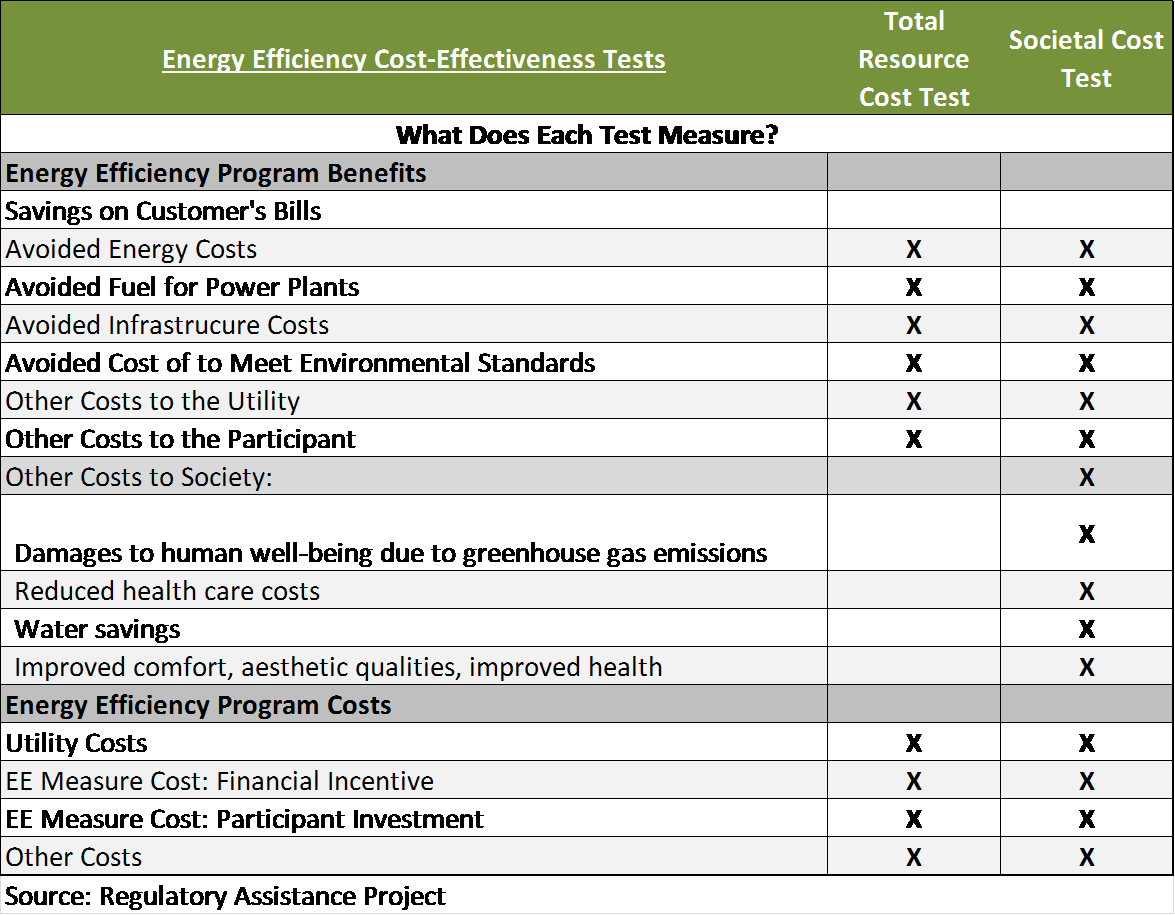

The three most commonly used resource cost tests are the:

- Societal Cost Test (SCT),

- Total Resource Cost (TRC) Test and

- Program Administrator Cost (PAC) Test (also called the Utility Cost Test (UCT).

The two least commonly used are the:

- Ratepayer Impact Measure (RIM) Test and

- Participant Test.

According to the American Council for an Energy Efficient Economy (ACEEE), 44 states plus the District of Columbia have ratepayer-funded energy efficiency programs, and some states use more than one test to determine their cost effectiveness. As an example, a state may use one test for individual efficiency measures and another test for the portfolio of all efficiency measures combined.

Breakdown of Tests

The Total Resource Cost (TRC) Test is the most common measure, but it has a major shortfall; namely, while all participant costs are counted, most or all of the benefits beyond the utility fuel savings (i.e. the offset amount of coal or gas for power plants) are not considered.

The Societal Cost Test (SCT) is used the least but is the broadest and most inclusive measure, accounting for externalities like environmental costs (e.g. the amount of carbon dioxide pollution avoided) and reduced costs for government services, such as health care. The challenge with the SCT is that it is very difficult to monetize most of these externalities and any over- or under-estimations could skew the entire cost effectiveness of a program. Further, some argue that the SCT takes into account issues that are outside the control of the utility, which could burden ratepayers with heavy costs. Six jurisdictions use the Societal Cost Test as either the sole or primary cost-effectiveness test: Arizona, District of Columbia, Iowa, Minnesota, Oregon and Vermont.

The TRC Test and the SCT may seem similar in that they both consider some avoided costs, like water, health and safety costs, but the primary difference is that the TRC looks at the benefits to utility customers while the SCT looks at the benefits to society.

Here’s another way to conceptualize the difference:

An easy way to conceptualize the difference is to decipher what question the test is trying to ask. For instance, the TRC Test asks, “Will the total costs of energy in the utility service territory decrease?” while the SCT questions, “Is society (the utility, state, region or nation) better off as a whole?”

The Texas Way

Texas, where I’m based, uses something called the Utility Cost Test. This is the state’s only cost-effectiveness test and it looks at limited costs and benefits. The costs include the design, planning, administration, delivery, monitoring and evaluation of a program, while the benefits account for avoided utility costs, such as building a new power plant and the purchase of fuel necessary to generate electricity. In other words, this test is limited to the impacts that would be passed on to customers through their electricity bills, disregarding other factors like impairing air quality and shrinking precious water supplies. The main question the UCT answers is, “Will utility bills increase as a result of implementing this energy efficiency program or project?”

In a state like Texas that values independence and private property rights, it’s not surprising that the main driver for evaluating the cost effectiveness of utility energy efficiency programs is cost to customers. And it’s a necessary and critical thing to consider. But it’s not the only thing to consider.

As climate change moves the needle toward more intense weather patterns, and as Texas faces a potential for electricity shortages, the state should consider adopting an energy efficiency cost test that evaluates a range of benefits from the energy efficiency programs, such as avoided fuel for power plants and the ability to meet clean air standards. This approach would enable energy efficiency to play a larger role in helping ensure greater grid reliability and cost savings. Texas policymakers can look to energy efficiency and its numerous benefits, both economic and environmental, to protect its citizens and natural resources from strain and depletion.