Smart Fisheries for the 21st Century

By Christopher Cusack, Rod Fujita and Katie Westfall

By Christopher Cusack, Rod Fujita and Katie Westfall

Global fisheries are at a crossroads. The demand for seafood is growing fast, and fishermen are expending ever-increasing effort to catch a declining amount of fish. We know how to fix this, and indeed, many fisheries are producing large and sustainable yields that benefit people and bring profit to fishermen. But too many marine ecosystems and communities still suffer from damaged ecosystems, illegal, unreported and unregulated fisheries and threats from human sources of pollution such as micro-plastics. And we face all of this under the increasing pressure that climate change will put on our ecosystems.

There are reasons for all this. For most of human history, the ocean has appeared to be so vast as to be unknowable, unfathomable and invulnerable. We thought that anything we did to it was just a drop in the bucket. We didn’t even think it was possible to overfish fish stocks until halfway through the last century. And it wasn’t until the 1990s that the great cod collapse and other fishery disasters brought home the fact that overfishing is possible and was occurring all over the world. And after we realized that fish stocks were becoming depleted, many fisheries failed to put in place the regulatory structures or knowledge needed to manage fisheries; we didn’t have the tools.

How were we supposed to manage fisheries without knowing how much fish were being caught, how much fish were left to catch and how changes in ocean conditions affected fish stocks, when we didn’t have the tools to collect and analyze the relevant data? Now, we have the tools to do all the things that are necessary for good fishery management. Tools that will help us not only mitigate current harm and repair harm that has already been done, but to embark on an entirely new paradigm defining our relationship with the ocean. One where the ocean is knowable, where we understand the relationships between what we do to ocean ecosystems and how they react — where we know how to monitor impacts and steer our management of the ocean on a path of sustainability, ecosystem health, industry profits and food provision for all future generations. In this blog, we’ll discuss the role technology and digital tools will play in steering us on this path.

Tools for a new paradigm

While models for successful fisheries management are aplenty, and there can be little doubt now that we have the scientific knowledge to effect the change we seek in global fisheries, stock assessments, rules and management structures alone are not enough — we’ll need help from Moore’s law.

A recent McKinsey report outlines categories of technological solutions or “advanced analytics” — integrated solutions that rely on advanced techniques of collecting and analyzing data — that are in widespread use in many industries, such as agriculture, shipping and tourism. These advanced analytics have the potential to help bring over $60 billion in annual benefits to marine fisheries over the next 30 years, through improvements in fisheries management, fleet operations and the seafood supply chain.

Advanced analytics will help to provide direct benefits to fishermen by increasing fleet operational efficiency — for example, by allowing vessels to find target species faster and reducing fuel usage and costs — and will improve the transparency of the global seafood supply chain, maximizing market value and engaging consumers in ocean stewardship. But the most exciting benefits will arise through our increased ability to understand how fish stocks interact with fishermen and their changing environment.

This proposition centers on the collection and use of more, and more types of, information: on the amount and types of fish caught, on the amount and types of fish that aren’t caught, on where fishermen catch (and don’t catch) fish, where sensitive habitats are, on oceanographic conditions and how fish move seasonally and in response to these conditions.

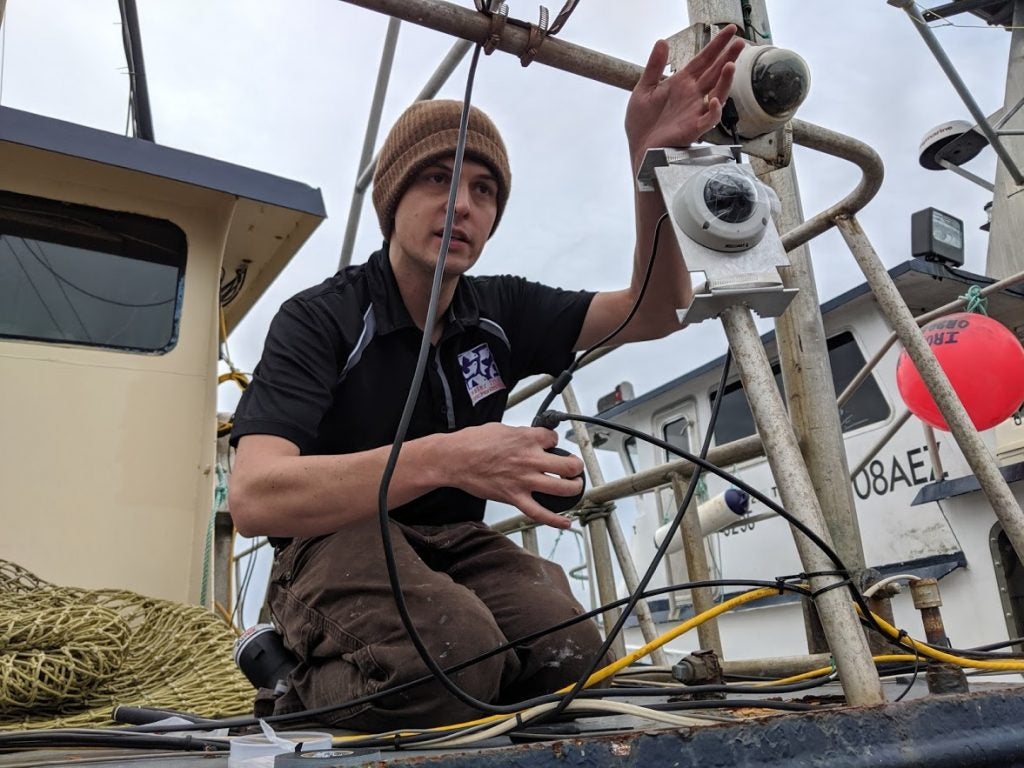

On-vessel sensors such as cameras and GPS transceivers that collect data on fish catch and position are being integrated with remote sensors, such as temperature sensors, on satellites to better understand how much fish are being caught, and where, and how oceanographic conditions can predict where certain species of fish are likely to be. Some are even capable of detecting microplastics in the water column. And instead of reviewing video data weeks after the fact to integrate these datasets, AI techniques are being used to automatically identify what is being caught in real time. And, on-vessel oceanographic sensor arrays are now being integrated with other sensor data using the Internet of Things. Rapidly improving cellular and satellite transmission capabilities are now making the real-time generation, integration and use of these huge datasets a reality. This is important, as it not only increases the reach of fishery management, it enables a new dynamic approach to management — an approach that holds the key to successfully managing fisheries in a changing world.

Instead of area closures that are static, we have the tools to design dynamic areas that can better protect the species they are designed to protect, while allowing fishermen to access species that don’t need protecting. Instead of static fish quotas, now we have the tools to design dynamic quotas that use current catch information as a basis for how much more can be caught. Instead of plotting a course across the ocean and sticking to it for the entire trip to the fishing grounds, we now have the tools to constantly update speed and direction, using less fuel and saving fishermen more money. Instead of static allocation formulas that can create conflict, spur overfishing and necessitate painful re-negotiations as stocks move, we now have the tools to implement flexible allocation formulas that automatically adjust to stock movements. The possibilities are endless.

Bringing Fisheries into the Digital Revolution

As the McKinsey report authors observe, the “untapped potential” of advanced analytics is currently only being tested in a handful of pilot projects around the world. So how do we make these advances a widespread reality? That’s where EDF’s Smart Boat Initiative comes in — to help promising new and emerging technologies become a reality through thought leadership, practical pre-implementation work, education and otherwise advancing the use of these technologies. We recognize that broad implementations are unlikely to be successful unless the range of human contexts are taken into account, which is why we use a human-centered design approach in our work. And we use a science-based approach to advocate for removal of policy and institutional barriers and creation of the incentives required for technology adoption. But the true essence of our work is that we always try to bring real value to fishermen and their communities, as we recognize that unless economic incentives are present, we are looking at an uphill battle.

In future blogs, we’ll talk specifics about the work we are doing in places as far flung as Indonesia, Mexico, Chile and the United States in bringing fisheries out of the dark ages and into the digital age.