Yesterday kicked off the official start of the “Climate Protection Plan” rulemaking in Oregon, a process that is likely to answer whether Oregon will follow through on meeting its strong commitments to climate action. The stakes for this critical rulemaking are high: Oregon had one of its most destructive wildfire seasons on record last year and faces far more devastating climate impacts in the coming decades, if climate-warming pollution continues unchecked.

While Governor Brown’s climate executive order from last year provides reasons for hope, there are already some red flags appearing as Oregon’s lead environmental agency dives into this rulemaking. EDF analysis provided here reveals how the pace and scale of Oregon’s policy action will impact total emissions this decade— and ultimately determine long-term climate damages.

Oregon’s climate targets

The legislature has committed to a number of climate targets—including an at least 80% reduction below 1990 level of greenhouse gas emissions by 2050—but has failed to adopt a plan to meet these targets or require an agency to do so. In March 2020, Governor Brown took the critical step of actually directing Oregon agencies to turn goals into action and meet the 2050 target and an interim target of at least 45% below 1990 levels by 2035.

The centerpiece of this Executive Order was a directive to the Oregon’s lead environmental agency to develop regulations to “cap and reduce” emissions from the state’s major sources of GHG pollution. She positioned this policy as effectively providing the backstop to ensure Oregon achieves its targets explaining that “caps will decline over time in order to meet our new greenhouse gas reduction goals.”

The Oregon climate action backstory

Governor Brown’s executive order followed two close attempts by the legislature in 2019 and 2020 to pass a climate program to achieve the reduction goals, but those attempts were stymied by Republicans shamelessly abandoning the Capitol to avoid a vote despite overwhelming support from Oregonians for action and majority support in the legislature.

Yesterday, Oregon’s Rulemaking Advisory Committee (RAC) for the Climate Protection Plan convened for the first time. The group is intended to provide a diverse perspective to inform the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) as it develops a rulemaking package to meet Governor Brown’s climate directives. Local environmental groups are raising important concerns that the composition of this group favors potentially regulated polluters over other stakeholder interests. While many members noted a desire to protect the climate for future generations and several business representatives mentioned emissions reduction efforts in their industry or company, the true commitment to policy action remains to be seen.

Near term reductions matter more than a 2050 target

As the RAC begins its work, EDF wants to send one clear opening message: Focus on a high ambition program that maximizes reductions as soon as possible, in the next 10 years. The IPCC’s 1.5 degrees special report illustrates that deep reductions are necessary by 2030 to have any chance of limiting warming to safer levels — to 1.5°C or even 2°C. Reducing emissions of short-lived climate pollutants (e.g. methane) – which govern the rate of near-term warming – is crucial for slowing the pace of warming. And reducing emissions of long-lived climate pollutants (e.g., carbon dioxide) – which govern the maximum extent of warming – is crucial for limiting the overall amount of warming, and therefore the full extent of the climate damages. The earlier a ton of carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere, the larger the cumulative buildup of long-lived pollutants will be and the greater the effect of that pollution on overall warming.

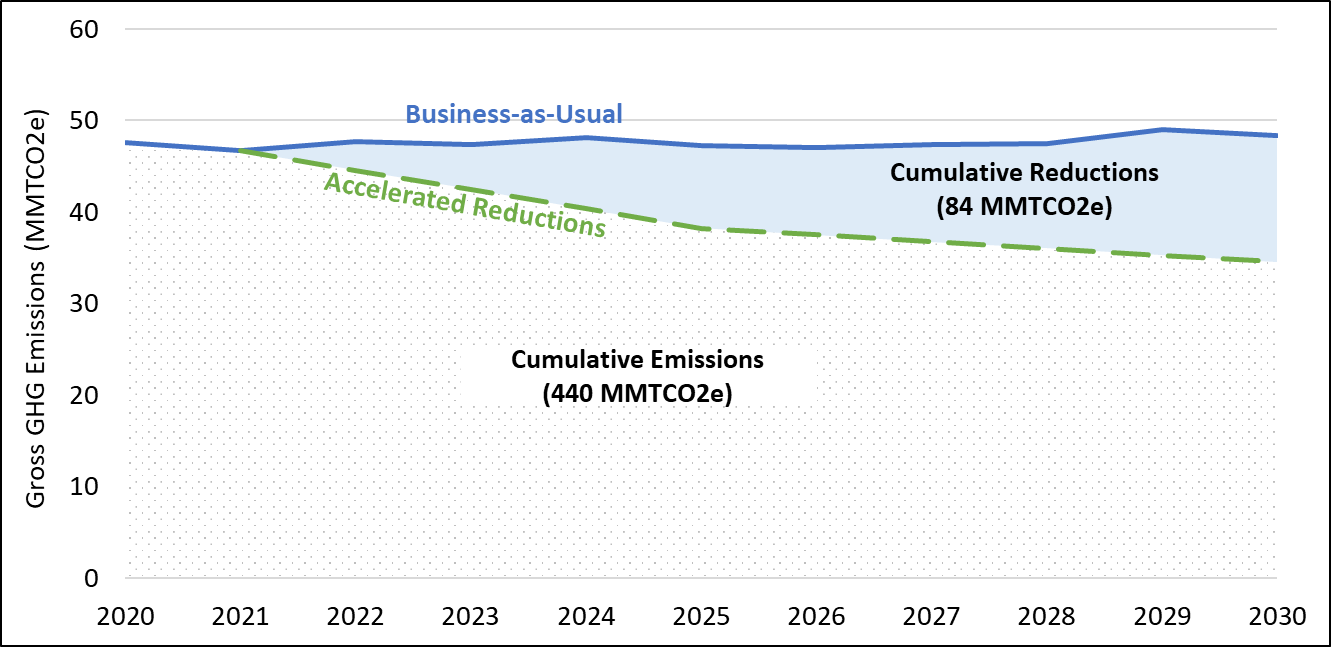

Figure 1 below, created by EDF for Oregon based on data from Rhodium Group’s U.S. Climate Service and Oregon’s own climate data, demonstrates the differences in this cumulative pollution build up based on different trajectories to the same 2030 climate target.

Figure 1: Differences in Cumulative Pollution Build up by Trajectory

The 2030 target shown in the figure reflects the emissions level needed to stay on a linear trajectory from 2021 BAU emissions to the state’s 2035 target, assuming the first reductions from the program takes place in 2022. The 2035 target was estimated based on Oregon’s GHG inventory. Note that the timeline only goes through 2030 because the Rhodium Group GHG emission projections we use for this analysis are only available through 2030. Power sector emissions in these projections are based on electricity consumption within the state, consistent with the state’s GHG inventory.

As illustrated in a business as usual (BAU) scenario, where no new climate policies are adopted, cumulative emissions rise far above the levels needed to meet Oregon’s 2035 target (which is estimated in 2030 here). The three other trajectories showcase the emissions impact of three different potential pathways for policy action:

- The delayed action scenario illustrates what might happen if reductions were really only achieved between 2025 and 2030. Hopefully this delayed action scenario will only be hypothetical—but if, for example, Oregon agencies drag their feet, adopt a weak program, phase in coverage for certain sectors, or fail to meet the Governor’s timelines, this type of reduction trajectory is what could be expected.

- The linear target trajectory represents the emissions decline trajectory that DEQ should achieve, at a minimum. This represents a straight-line reduction between expected BAU emissions in 2021 (just before the program is expected to begin in 2022) and the 2035 E.O. target of 45% below 1990 emissions levels by 2035. Again, we have calculated what the equivalent number is in 2030 since our projections do not go further.

- The accelerated reductions trajectory is another illustrative scenario that demonstrates even better climate outcomes if Oregon decides to frontload reduction efforts before 2025.

The takeaway from these three scenarios is: The faster Oregon moves to enact a strong limit on emissions, the faster it can curb the dangerous buildup of emissions in the atmosphere.

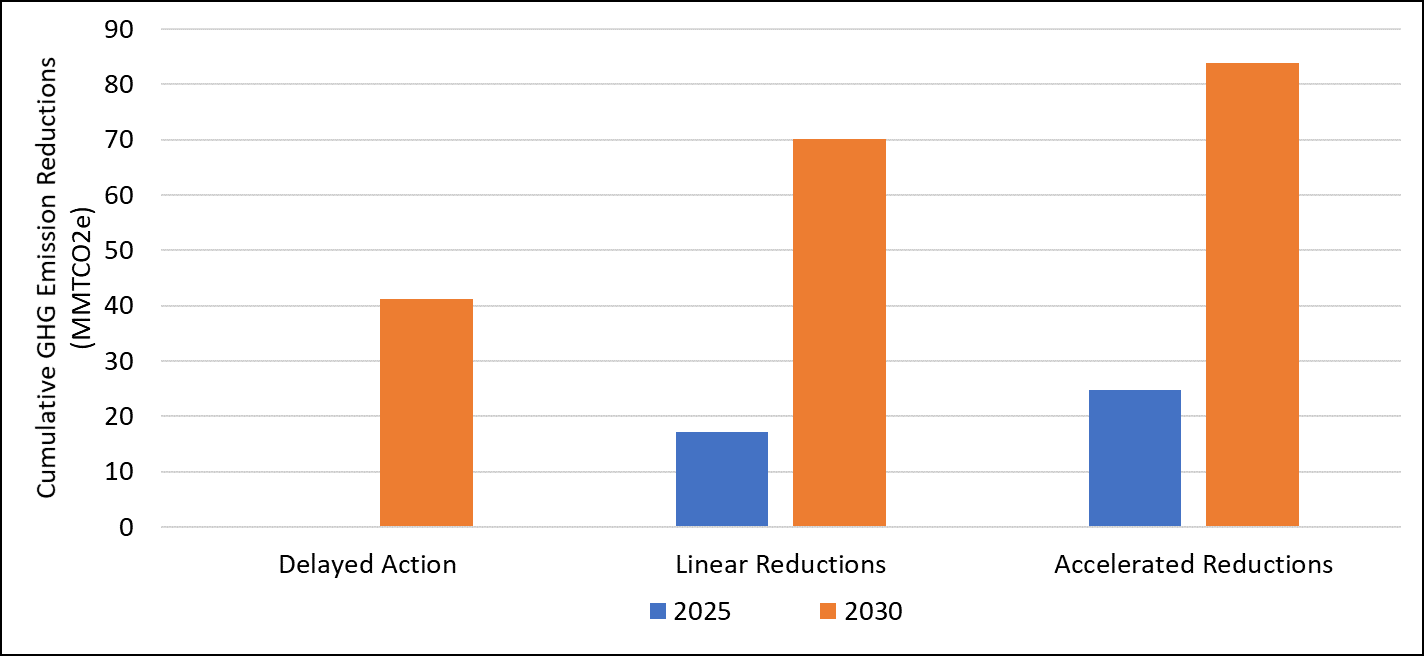

Figure 2: Cumulative Reductions differences between a BAU Scenario and Accelerated Scenario

As shown in Figure 2, pursuing more up-front policy action in an accelerated reduction scenario could avoid more than 80 million metric tons CO2e of pollution. Allowing that pollution to build up will have real impacts on Oregon’s communities, ecosystems and economy.

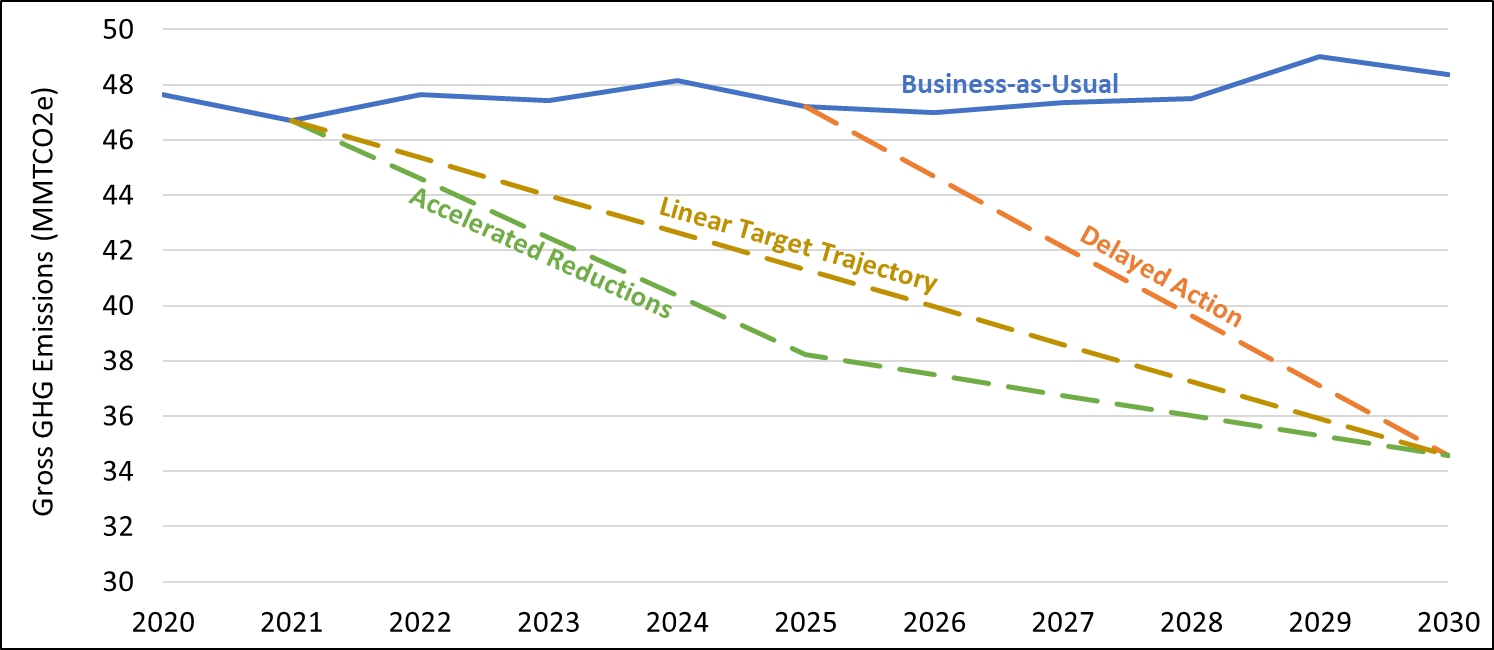

Figure 3: Cumulative Emissions Reductions in 2025 and 2030

And finally, Figure 3 shows that an accelerated reduction scenario will result in twice as many cumulative reductions by 2030 as the delayed action scenario with the linear scenario not far behind, even though all scenarios reach the same end point in 2030.

Oregon is a national climate leader, can they keep it up?

A recent analysis by EDF demonstrates that while many states have made climate commitments, most face a gap between the goals they’ve set and the reductions expected from laws on the books. Oregon is providing a critical national model by engaging in a rulemaking specifically designed to ensure the state meets its targets. Governor Brown’s executive order took a few essential steps that move Oregon further than most other states.

First, she brought the full power of her administration to bear on the climate crisis by prescribing and calling for climate action at numerous Oregon agencies. And even more importantly, she gave one agency, the Department of Environmental Quality, primary responsibility for designing regulations that will reduce emissions in major emitting sectors consistent with climate targets.

EDF’s analysis of the gap between commitment and action demonstrate that surgical actions, including adopting clean car standards and other critical efforts, are not enough to close the gap—so this step by Governor Brown is critical.

It remains to be seen whether the regulations DEQ proposes will meet the challenge that Governor Brown has set before them. A few of the areas of concern that EDF and other advocates will be watching include:

- Is the program designed to truly ensure that Oregon meets its climate targets, and are opportunities for cumulative pollution reductions being missed?

- Will this program—that should function as Oregon’s backstop policy, ensuring economy-wide emissions reduction targets are met—cover all major emitting sectors in Oregon? DEQ has stated that the program is not “well-suited” to regulating emissions from the electricity sector, which offers some of the best near-term opportunities to reduce climate pollution and is Oregon’s second largest source of greenhouse gas emissions. 15 other states have firm limits on carbon pollution from the electricity sector and this move could leave Oregon far behind.

- Will Oregon create a program that promotes equity and justice by targeting benefits and pollution reductions towards frontline communities and populations that are historically underserved? Or will the design of the program ultimately favor polluters at the expense of the people in Oregon who are already suffering from the impacts of climate change.

Watch this space in the future for more in-depth discussion of these topics in Oregon. As EDF’s work has shown, the gap between commitment and action can be significant. That’s why Rulemaking Advisory Committee members, Department of Environmental Quality staff, the Environmental Quality Commission and the Governor’s office should take this opportunity to set rules that can deliver the meaningful climate action Oregon needs.