This post is by Tony Kreindler, media director for the National Climate Campaign at Environmental Defense Fund.

This post is by Tony Kreindler, media director for the National Climate Campaign at Environmental Defense Fund.

The main reason to pass climate legislation as soon as possible is that the fate of the world is at stake. We’re in a race against time to stop global warming, or face irreversible climate catastrophe.

But there’s also another race – the race to develop the clean energy technologies that will power our future. The world is at the dawn of a technological revolution, and we need the economic incentive of climate legislation to fully participate.

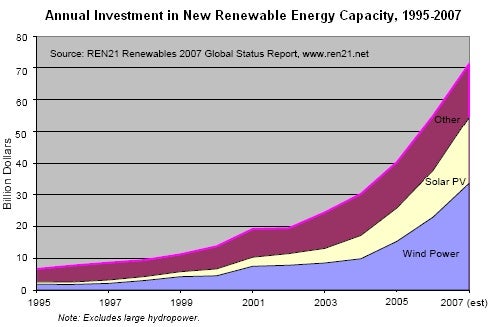

Global investment in clean energy is growing – rising to over $70 billion in 2007, as you can see in the graph below. But it isn’t enough.

Source: REN21 2007 Global Status Report. Used with permission.

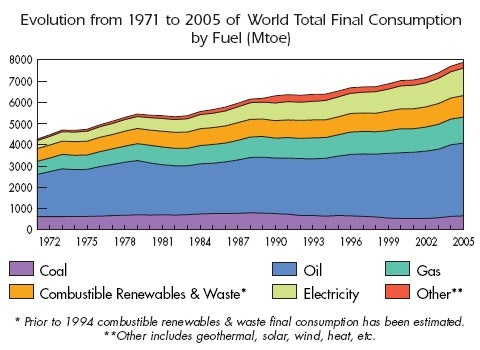

When you look at total world energy consumption over time, you can see how far we still have to go. In the graph below, renewables are shown in red. They’re growing as a percentage, as you can see, but they still provide only a small fraction of the energy we use.

Source: IEA Key World Energy Statistics 2007.

What will it cost to meet future world energy needs? Global Energy Perspectives examined this question under different scenarios. The scenarios that minimize global warming have the lowest costs, but the cost of meeting future energy needs – no matter how it’s done – is massive. The green (lowest-cost) scenario still requires over $9 trillion in energy investment from 1990 to 2020, and over $14 trillion from 2020 to 2050. That comes out to nearly $400 billion per year invested in renewables.

When you put it that way it seems overwhelming, but we’re poised to do it. Here are just a few of the promising projects in the works (from Earth: The Sequel):

- Cheaper solar energy from silicon nanocrystals dissolved in ink that can be printed onto any surface, including roofing material.

- Redesigned viruses that assemble themselves into the most powerful batteries ever seen.

- Reengineered yeast fermenting sugar into pure hydrocarbon fuel that any car, truck, or plane can use.

- Biodiesel fuel from algae feeding on power plant smokestacks – priced competitively with diesel made from $60/barrel oil.

- Clean, renewable energy from tides, waves, and geothermal heat.

But to bring these projects to market at a speed and scale sufficient to halt global warming, we must have the strong economic incentive of cap-and-trade legislation. Dupont CEO Chad Holliday, quoted in Earth: The Sequel, explains why this is so important:

You need some certainty on the incentives side and on the market side, because we are talking about multiyear investments, billions of dollars that will take a long time to pay off.

A similar view is expressed by the CEOs who lead the World Business Council for Sustainable Development in their report Investing in a Low-Carbon Energy Future in the Developing World [PDF]:

A lack of certainty over policies related to carbon pricing and GHG [greenhouse gas] reduction targets increases the risk of achieving a commercial return for low-GHG technology projects. While this uncertainty prevails, the bulk of potential private capital available will probably flow to traditional energy sources, or remain uncommitted until definitive policies, which underpin a pragmatic approach, begin to emerge.

These CEOs know what they’re talking about. A study of global trends in renewable energy investment [PDF] found that a mandatory cap and carbon market significantly strengthen renewable energy companies:

The ‘Kyoto Effect’ can be observed, with quoted renewable energy companies in countries that have ratified the Protocol outperforming those in non-ratifying countries by 41.3%.

We’re at the dawn of a global energy revolution. If we are to lead the world in clean energy technologies, we must create an environment that allows U.S. businesses to act. If we wait too long to pass climate legislation, we may find ourselves buyers rather than sellers.

4 Comments

Cap and Trade is not the only way. Carbon taxes DO provide price certainty — making it easier to project investment returns to green technologies. See my post from today: http://aguanomics.com/2008/05/carbon-tax-or-cap-and-trade.html

Actually, that is exactly the problem. A carbon tax provides price certainty, but not greenhouse gas emissions certainty. What we need is the latter, and that is what a cap-and-trade system provides – emissions certainty. A well-designed cap-and-trade system can provide adequate price flexibility as well.

Nat Keohane, a Ph.D. economist here at EDF, wrote a great post explaining why a tax is the wrong tool for a job and cap-and-trade is the right tool. He wrote this in response to a phone call from the head of the Congressional Budget Office objecting to his review of a study they’d published. This is a good read – take a look:

http://blogs.edf.org/climate411/2008/03/04/cbo_followup/

I disagree about the “certainty” aspect of cap and trade. While true in theory, real emissions will be uncertain to the extent that emissions are unmeasured or mismeasured. Take the measurement of population. In the US, the census is considered to be “fairly” accurate, but naysayers complain about various important groups (homeless, migrants, et al.) being unmeasured.

Now consider how most countries do not even know their populations — and multiply that mismeasurement by — say — 120 (census once per decade versus monthly emissions measurements). Carbon taxes are much simpler to enact, measure, and enforce (except for gathering and burning wood — but they are likely to be missed in cap and trade too).

I took a look at Nat’s post. While I agree with him (and my PhD is younger than his), I think he is leaving out another “transactions cost”-related aspect of cap and trade that does not exist with carbon taxes. Say that permits are issued on an annual basis (by auction), that a bank exists, etc. but it’s “suddenly” discovered that too many permits are out there. The next auction must reduce the number of permits AND policing “black market” emissions must increase.

With taxes, the response is only to increase the tax on carbon inputs. That increase can occur on or before the date for the next auction, and there is no need to police emissions, since taxes are part of the prices at the start — not end — of the carbon-generating cycle. It’s much harder to have a black market input (coal from a different mine) than black market output (coal burned in a burner without a permit).

Taxes are better because they are simpler AND easier to adjust. Forget the theory — these systems have to work, worldwide, in reality.

Yeah, me too.

Another carbon taxer here.

I also read Nat’s piece and I am sure we will talk soon.

I find his arguments on the CBO study really questionable, almost specious.

He had two.

One was that the CBO analysis was on a “straw-man” inflexible Cap.

I’ve seen that argument elsewhere.

It’s not true.

They also combined the Cap with banking OR a Floor price; and the Cap with a Safety-valve and “managed borrowing”.

These ARE the options that have been bantered about in legislative proposals.

In EVERY case, the CBO report found the carbon tax was superior in the efficiency of achieving our CC goals.

What Nat fails to identify, and what I feel he owes us, is exactly WHAT combination of “C&T&WHAT” he would like to see modeled against the carbon tax, in order for the carbon tax to be found to be the most cost-effective means of achieving our goals.

“Dear CBO – The CC legislation WILL contain the following policy parameters. Please model against the carbon tax.”

And to say WHY he is certain that such a policy choice is the one that will ultimately be included in the CC legislation that passes.

Absent such a position, his “straw-man” argument has no validity in my humble opinion.

He claims the CBO finding that a carbon tax is superior to even the most flexible Cap-and-Trade policy is “flawed” because it is based on some estimated measure of the marginal cost of emissions-management.

He doesn’t fault the estimated value, he faults the fact that it will change in value over time – primarily driven by the fact of some unidentifiable “tipping points” in GHG management.

It may surprise NAT and EDF to know that some people out there want to know, for good reason, what this thing is going to cost.

That cost will be determined either by what the flexible carbon tax will be set at, or it will be determined in a free-market inhabited by wildcat speculators in financial service products. Thanks, EDF for your choice.

I don’t know why any economist would be promoting any solution that does not get us to our goals as cheaply as possible.

Finally, he complains that the CBO only modeled the “emissions” that need controlling as a policy tool, as opposed to the resulting levels of GHG in the atmosphere.

The only thing we can regulate via our policies are levels of emissions.

He says as much.

He admits that “traditional” economic thinking puts us in that analytical posture.

Yet, he claims that such analysis is somehow flawed.

When you read the language of the BlueDog and other Democrats on the Boxer and Warner bills, you better understand that the cost of solving our CC goals WILL BE a major factor in getting the sixty votes.

There is nothing in Nat’s piece that convinces me that a C&T system is anything but a fool’s mission.